By Jesse Newman and Bob Tita

For nearly two centuries, Deere & Co. has built equipment to

help farmers plant and harvest their crops. Now, the company's

financial muscle is doing more of the work.

Throughout the Farm Belt, low prices for corn, soybeans and

wheat are putting a strain on U.S. grain farmers, making it harder

to get bank lending to plant a crop, or commit to purchasing

multimillion-dollar fleets of new equipment.

Deere, the world's largest manufacturer of tractors and

harvesting combines, is stepping in to fill the gap. It already

lends billions to finance farmers' purchases of equipment. Now, it

is providing more short-term credit for crop supplies such as

seeds, chemicals and fertilizer, making it the No. 5 agricultural

lender behind banks Wells Fargo, Rabobank, Bank of the West and

Bank of America, according to the American Bankers Association.

Deere has also expanded its leasing program to get the company's

green and yellow tractors into the hands of farmers, even when they

are unable or unwilling to pay hundreds of thousands of dollars to

buy one.

Its financing has helped farmers stay in business while

generating income for Deere during the worst market for machinery

sales in more than 15 years.

Farmers' incomes will decline for a fourth year this year, to

half what they were in 2013, the U.S. Department of Agriculture

projects. And inflation-adjusted debt is at a level not seen since

the 1980s farm bust.

In shoring up the ailing sector, Deere's loans may be helping

draw out the pain for farmers, allowing them to continue to rack up

debt despite a glut of grain world-wide that is keeping a lid on

crop prices. The increase in equipment leasing, meanwhile, is

weakening Deere's own market for sales.

If crop prices remain subdued, "you're just prolonging the agony

and potentially building up [farm] losses instead of cutting the

pain, cauterizing the wound and stanching the flow of financial

blood now," said Scott Irwin, an agricultural economist at the

University of Illinois.

But if poor weather ultimately spurs grain prices higher, Mr.

Irwin said, the risks of farm lending likely would be forgotten,

and Deere could win new or more loyal customers.

Deere said it is responding to greater demand for leased

equipment from farmers and for short-term credit from other

farm-industry manufacturers such as seed companies that are

offering aggressive financing through Deere as a sales

incentive.

"Our core mission is to support sales of equipment," said Jayma

Sandquist, vice president of marketing for the U.S. and Canada for

John Deere Financial, the company's financing unit. "It's a

cyclical industry. We've built a business that we can manage

effectively across all cycles, and our performance would indicate

we can do that."

The financing arm has shielded the Moline, Ill., company from

the worst of the farm slump, keeping factories and dealers intact

and investors satisfied with profits. Despite a 37% drop in sales

of its farm equipment since a record high in 2013, Deere's stock

price is up 72% from its recent low in early 2016 and up 22% since

the start of 2017.

Deere Financial's portfolio of loans and leases, which includes

short-term lending, leasing and multiyear loans for equipment

purchases, totaled $34.7 billion at the end of the company's 2016

fiscal year, in October.

Since 2013, the total value of equipment leases held by Deere is

up 87%. Loans for farm equipment purchases, meanwhile, have fallen

10% since peaking in 2014, reflecting sliding machinery sales.

Short-term credit accounts for farmers -- used for items such as

crop supplies and equipment parts -- are up 38% since the end of

2015. As of early 2017, the bank operation of Deere Financial had

handed out about $2.2 billion. It is close on the heels of the No.

4 agricultural lender, Bank of America, which has about $2.6

billion out.

"Deere Financial is a massive force," said Robert Wertheimer, a

Barclays analyst. Deere, which accounts for about two-thirds of all

the big tractors sold in the U.S., "is able to influence this

market. They have more market power than most companies."

Rob Zeldenrust, senior agronomy manager at North Central Co-op

in Mentone, Ind., said a farmer who grows corn, soybeans and wheat

on 1,000 acres likely would need $250,000 to cover the cost of

seed, fertilizer, chemicals, spraying and fuel for a single growing

season.

Suppliers like Deere can be a lifeline for farmers such as

59-year-old Harry DuRant in South Carolina. Mr. DuRant leases a

tractor from Deere, and has charged seed and chemical purchases to

lines of credit held by Deere and other suppliers. Together with

loans from his local bank, the financing has helped him plant corn,

soybeans, peanuts, cotton and other crops despite losing money for

three years out of the past four. It has helped him weather floods,

a hurricane and total crop failure.

But low commodity prices are making it difficult for Mr. DuRant

to pay off past debts without taking on new ones. "It's a vicious

cycle," Mr. DuRant said, noting that seed companies continually

introduce more expensive, higher-yielding varieties of corn and

soybean seeds that appeal to farmers like himself, despite a global

oversupply of crops and low grain prices. "I buy into it because

I'm a grower, so of course I want to make 150-bushel corn instead

of 120-bushel corn. All we're doing is making the situation

worse."

Supplier credit has long played a role in the financial plumbing

of the U.S. heartland. But it has grown more crucial in recent

years as commercial banks have become choosier, increasing interest

rates and collateral requirements and denying financing for some

farmers altogether.

The volume of new loans for farm operations originated by banks

in the first half of 2017 fell 7% from a year earlier, according to

the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, following a decline in the

first half of 2016. Loan volumes in the second quarter ticked up

slightly, the bank said.

"It used to be you showed up [at a bank] and said you were a

farmer and they said please let us lend you something," said

Illinois farmer Aaron Wernz, noting that several years ago a

$100,000 loan for operating expenses could be secured with a phone

call. "Now they want to make sure their t's are crossed and i's are

dotted."

Nate Franzén, president of the agribusiness division of First

Dakota National Bank in Yankton, S.D., said the number of high-risk

loans at his bank has quadrupled to 12% in the past two years. The

bank is working to restructure debt for some borrowers, and urging

others to sell land or equipment or vacation homes. He has had to

tell a few farmers it couldn't finance them at all.

"As producers get overextended, banks like mine say 'I can't go

any further,' " said Mr. Franzén. " 'We're not going to stick with

you until it's all gone.' "

Agribusinesses such as Monsanto Co., DuPont Co., Dow Chemical

Co. and agricultural co-ops nationwide offer financing on crop

supplies through in-house programs or in partnership with lenders

like Deere and Rabobank.

BASF SE, one of the world's largest suppliers of pesticides to

farms, offers financing exclusively through Deere, and says its

program has expanded in the past five years.

CHS Inc., a large farmer-owned cooperative in the U.S. that

lends widely to farmers, is holding about $250 million in debts

owed by a single farm operation, according to court documents.

Deere's main rival, CNH Industrial NV -- the maker of CaseIH and

New Holland equipment brands -- has also turbocharged its leasing

program.

But Deere has expanded the reach of its financing business well

beyond machinery, and far more than any other manufacturer in the

farm sector. The financing business accounted for a third of its

net income in fiscal 2016, up from 16% in 2013.

Deere's lending arm regularly yields profit margins much greater

than Deere's margins for equipment sales -- in 2016, the net margin

for financial services was 16%, compared with 4.5% for

equipment.

Financing profits have also suffered less during the downturn;

net income from financing activities fell 17% from 2013, while net

income from the equipment business plunged 57% in that period.

But Deere's loan or lease balances more than a month past due

have doubled since 2012 to $434 million at the close of fiscal

2016, according to an annual regulatory filing for a Deere

financial subsidiary for its U.S. business.

The amount of debt Deere said it won't be able to collect has

doubled since 2014 to $103 million, with more than half of that

amount from its crop-supplies credit program.

Losses at Deere's financial arm still remain minuscule relative

to the size of its finance business. The company said mounting farm

debt isn't a significant risk given still-high equity levels -- the

difference between total assets and total debt on farms. "We have

many good customers that can continue to repay and stay consistent

across underwriting," said Deere's Ms. Sandquist.

In the longer term, Deere's aggressive leasing activity

threatens its core business of selling large, high-horsepower

tractors that can cost more than $200,000 a piece, and harvesting

combines priced at more than $500,000.

Deere accelerated its equipment leasing in 2014 when sales

plummeted following almost a decade of rapid-fire purchases by

farmers flush with cash. The leasing business has kept Deere from

having to idle factories and has provided dealers with income from

replacement parts and services for leased equipment.

In turn, it has provided farmers with machines for one to three

years for a fraction of their purchase price, alleviating the need

for loans. A new tractor costing $250,000 can be leased for about

$30,000 a year. That compares with the cost to buy with a loan,

which would require a 20% down payment of $50,000 and more than

$40,000 a year in payments for five years for the remaining

$200,000 with 5% interest.

"What a lease afforded [farmers] was a payment that was

predictable," said Deere's Ms. Sandquist. "We didn't set about a

strategy to use leasing."

At the end of a lease, many farmers have returned their

machinery to dealers, adding to an already oversupplied market for

used equipment. That pushes down the price farmers who own can get

for their used machines, discouraging trade-ins for new models. The

lower prices also erode profits for Deere when the machinery is

eventually sold.

"We see the value of used equipment dropping off," said Cameron

Hurnard of Iron Solutions Inc., which tracks prices for late-model

used farm equipment.

Deteriorating prices for used equipment and the reluctance to

take on more debt are souring many farmers on owning as an

investment to build farm equity, which had been a key selling point

for Deere's high-value machinery.

"I don't believe I'll ever buy again," said Mark Gath, a farmer

in Luverne, Minn., who recently decided to lease four combines and

five tractors from the company instead of borrowing money to buy.

"I don't have a bank looking at me saying: 'You've got $5 million

of equipment debt. What are you going to do?' "

At the end of fiscal 2016, Deere carried leases on farm and lawn

equipment worth $4.8 billion, up 22% from the previous year.

Deere quit offering one-year leases last year when it

experienced a deluge of returned equipment that the company had

originally valued at higher than the market for used equipment.

Eliminating short-term leases pushed down the new-lease volume this

year, but farmers are still taking longer leases. The longer-term

contracts benefit Deere by having farmers pay more of the

machinery's cost through their payments.

Deere executives said they are seeing better prices and

shrinking inventories for used equipment, as well as improving

order volume for new models.

Ms. Sandquist said farmers' interest in leasing is waning as

their appetite for buying grows again. "We are certainly seeing

leasing coming down, and we're seeing stabilization in used

values," she said.

The company increased its equipment sales growth forecast for

the year to 9% from 4% in May, and it cranked up its net profit

outlook to 33% growth, to $2 billion.

The longer low commodity prices persist, however, the less

effective equipment leasing will be at injecting life into the new

machinery market, say some analysts. What Deere has done "spreads

out the pain but it can't eliminate it," said Barclay's Mr.

Wertheimer.

On the other hand, if adverse weather boosts grain prices in the

long run, "then what John Deere is doing is very smart," said Mr.

Irwin, the University of Illinois agricultural economist, about

Deere's overall financing activities. "They're providing the

financial cushion and waiting for bad weather."

Turning farmers like Michael Oliver into buyers again will be

critical for Deere's future.

Mr. Oliver, who farms 32,000 acres near Cadiz, Ky., said he used

to trade in and purchase about $12 million worth of machinery --

seven combines and a dozen tractors -- every year before sliding

crop prices caused him to start leasing three years ago. But he

recently concluded that even that was too costly. He is now

extending warranties on old equipment he already owns, saying:

"We're going to use our own equipment, and it looks like we're

going to be keeping it for a while."

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

July 18, 2017 13:44 ET (17:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2017 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

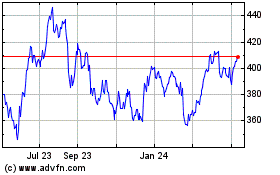

Deere (NYSE:DE)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

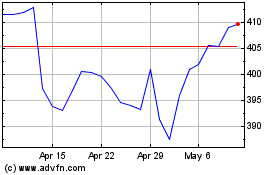

Deere (NYSE:DE)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024