By Melanie Evans and Anna Wilde Mathews

Black patients were less likely than white patients to get extra

medical help, despite being sicker, when an algorithm used by a

large hospital chose who got the additional attention, according to

a new study underscoring the risks as technology gains a foothold

in medicine.

Hospitals use the algorithm -- from Optum, UnitedHealth Group

Inc.'s health-services arm -- to find patients with diabetes, heart

disease and other chronic ailments who could benefit from having

health-care workers monitor their overall health, manage their

prescriptions and juggle doctor visits, according to the study

published Thursday in the journal Science.

Yet the algorithm gave healthier white patients the same ranking

as black patients who had one more chronic illness as well as

poorer laboratory results and vital signs.

The reason? The algorithm used cost to rank patients, and

researchers found health-care spending for black patients was less

than for white patients with similar medical conditions.

"What the algorithm is doing is letting healthier white patients

cut in line ahead of sicker black patients," said Dr. Ziad

Obermeyer, the study's lead author and an acting associate

professor of health policy at the University of California,

Berkeley.

Optum advises its customers that its predictive algorithms

shouldn't replace physician judgment, a company spokesman said.

Efforts to use analytics in health care have only scratched the

surface of their potential and should be continually reviewed and

refined, he said.

Optum's algorithm is used by more than 50 organizations,

according the company's website. Partners Healthcare in Boston is

among those to have used it, according to published research. A

Partners spokesman said the hospital system is vigilant about how

well its algorithms perform. He added a Partners researcher

co-authored the paper, which "is an important step in rooting out

some of the flaws that exist."

The Washington Post and Science News earlier reported Optum is

the algorithm's developer.

Algorithms, developed by computers crunching vast data sets, are

increasingly shaping choices in medicine, from interpreting medical

scans to predicting who might become addicted to opioids, suffer a

dangerous fall or end up in the hospital.

The technology can speed up and improve some decisions, leading

to better treatment for patients, supporters say. But doctors who

get suggestions to tweak their patients' care based on the findings

of algorithms often don't know the details of the technology that

led to the recommendation.

Poorly designed algorithms risk reinforcing racial and gender

biases, technology experts caution, as studies of algorithms in

nonmedical settings like credit scoring, hiring and policing have

found.

Algorithms "can give the gloss of being very data-driven, when

in fact there are a lot of subjective decisions that go into

setting up the problem in the first place," said Solon Barocas, an

assistant professor at Cornell University who is also a principal

researcher at Microsoft Research.

Researchers behind the study said well-designed algorithms could

help reduce bias that leads to wide disparities in health-care

outcomes and access to care. They created an alternative algorithm

that increased the percentage of those identified for extra help

who were black to about 47%, up from 18%.

"It's a tool that can do a great deal of good and a great deal

of bad, it merely depends on how we use the tool," said Sendhil

Mullainathan, a University of Chicago computational science

professor who was an author of the study.

Hospitals and health insurers across the U.S. use the Optum

algorithm to spot patients who could benefit from extra help from

nurses, pharmacists and case workers, the authors of the study

said.

To identify those with the biggest medical needs, the algorithm

looks at patients' medical histories and how much was spent

treating them, and then predicts who is likely to have the highest

costs in the future.

For the study, data-science researchers looked at the

assessments made by one hospital's use of the algorithm. The study

didn't name the hospital. The researchers focused on the

algorithm's rankings of 6,079 patients who identified themselves as

black in the hospital's records, and 43,539 who identified as white

and didn't identify themselves as any other race or ethnicity.

Then the researchers assessed the health needs of the same set

of patients using their medical records, laboratory results and

vital signs, and developed a different algorithm.

Using that data, the researchers found that black patients were

sicker than white patients who had a similar predicted cost. Among

those rated the highest priority by the hospital's algorithm, black

patients had 4.8 chronic diseases compared with 3.8 of the

conditions among white patients.

The researchers found the number of black patients eligible for

fast-track enrollment in the program more than doubled by

prioritizing patients based on their number of chronic conditions,

rather than ranking them based on cost.

The findings show "how a seemingly benign choice of label (that

is, health cost) initiates a process with potentially

life-threatening results," Ruha Benjamin, author of "Race After

Technology" and an associate African-American studies professor at

Princeton University, said in an accompanying commentary in

Science.

Algorithms are playing an increasing role in medicine, though

largely invisible to patients.

Doctors are using algorithms to read scans for lung cancer, for

instance. Hospitals are deploying the technology to spot which

critically ill patients are likely to worsen dramatically.

Meantime, health insurers are using algorithms for reasons

including to detect patients who are at risk of opioid addiction or

who appear headed toward costly lower-back surgery.

Alan Muney, a former executive at health insurer Cigna Corp.,

said it is common for insurers to use the projected cost of care as

a focus in selecting who might get extra outreach or support.

"It's troubling there was such a big difference" in the effects

for black and white patients based on an algorithm focused on cost,

he said.

Insurers are developing algorithms that include variables beyond

medical costs, including issues that might signal barriers to

accessing care, such as financial stress and food insecurity, he

said.

Write to Melanie Evans at Melanie.Evans@wsj.com and Anna Wilde

Mathews at anna.mathews@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

October 25, 2019 08:54 ET (12:54 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

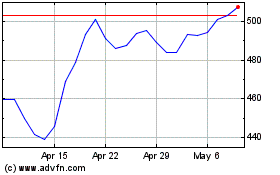

UnitedHealth (NYSE:UNH)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

UnitedHealth (NYSE:UNH)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024