By Denise Roland

This article is being republished as part of our daily

reproduction of WSJ.com articles that also appeared in the U.S.

print edition of The Wall Street Journal (July 24, 2019).

Genetic test-kit company 23andMe Inc. has for years used saliva

to tell millions of consumers how closely related they are to

Neanderthals or whether they are likely to develop diseases like

diabetes or Alzheimer's. Now, it's fulfilling a bigger ambition:

drug development.

For the past year, 23andMe has been sharing its huge trove of

genetic data with drug giant GlaxoSmithKline PLC, which took a $300

million stake last summer. That collaboration has so far produced

six potential drug targets, and the companies expect to start human

trials on at least one candidate drug next year. But it also raises

ethical questions about using people's genetic data to create

profitable drugs.

For 23andMe, using genetic data for drug research "was always

part of the vision," according to Emily Drabant Conley, head of

business development. Since its founding in 2006, the company has

amassed a huge collection of data from the millions of people who

have submitted spit samples -- and up to $199 each -- in return for

insights on their genes. The company says it has sold around 10

million test kits and analyzed more than eight million people's

DNA, making it the largest repository of human genetic information

in the world.

That information is especially valuable to drugmakers because

the majority of 23andMe's customers also choose to answer

questionnaires on their health. Analyzing millions of people's

genetics alongside data on their overall health provides clues on

the interplay between genetics and particular ailments, creating

potentially fruitful avenues for drug discovery.

For Glaxo, the 23andMe deal is part of a wider effort to use

genomic data to hunt for new drugs. The company also is involved in

research projects with government-funded genome collections in the

U.K. and Finland. It hopes that genomics could help solve a problem

that plagues the pharmaceutical industry: a high failure rate in

turning promising leads into drugs that work.

"The industry is in a very inefficient place right now," said

John Lepore, who heads early-stage research at Glaxo. "We're

spending tens of billions, but the number of new medicines turning

out is not high." The British company estimates that drugs based on

genetic information are twice as likely to succeed in clinical

trials as those that aren't.

Others are making similar bets. Amgen Inc. bought deCODE

Genetics, which started out as an initiative to gather genetic data

from the Icelandic population, to help it hunt for potential drug

targets. Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. is working with dozens of

hospitals and research groups seeking clues to the genetic causes

of disease.

23andMe has long wanted to use genetic data for drug

development. Initially, it shared its data with drugmakers

including Pfizer Inc. and Roche Holding AG's Genentech but wasn't

involved in subsequent drug discovery. It later set up its own

research unit but found it lacked the scale required to build a

pipeline of medicines. Its partnership with Glaxo is now

accelerating those efforts.

Glaxo expects the collaboration to accelerate the costly and

arduous process of finding patients to join clinical trials.

Typically, drugmakers rely on advertisements and doctors to spread

the word about trials, and not all patients who express an interest

are eligible.

One of Glaxo and 23andMe's targets is a rare mutation in a gene

called LRRK2 that raises the risk of developing Parkinson's. Around

one in a thousand people are carriers, which would make them very

difficult to find using traditional trial-recruitment tactics.

23andMe has contact details for 7,500 carriers it can invite to

participate.

Dr. Lepore estimates that could shave "months, if not years" off

the trial-recruitment process.

23andMe asks customers to consent to their genetic information

being used for research purposes, and the firm says 80% say

yes.

Still, some critics say it isn't ethical for 23andMe to profit

from a database built from the genetic data of paying

customers.

"You get this gigantic valuable treasure chest, and people are

going to wind up paying for it twice," said Arthur Caplan, a

professor of bioethics at NYU School of Medicine. "All the people

who sent in DNA will be paying the same price for any drugs that

are developed as anybody else."

A 23andMe spokesman said its customers are making an informed

choice to allow their genetic information to be used in research.

The company says it only shares high-level summaries of its data

with Glaxo, but the partnership highlights a broader privacy

concern: that 23andMe's customers may not have realized their data

would be used by the pharmaceutical industry.

"Consumers really need to think about what they're getting

into," said Richard Forno, assistant director of the Center for

Cybersecurity at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County.

"Where's that data going, and who's getting it?"

A 23andMe spokesman said customers are sent letters informing

them about for-profit collaborations, and that they have the option

of withdrawing consent for that research.

For some, the benefits outweigh the drawbacks. Reni

Winter-Evans, 64, sent her saliva to 23andMe last year, after a

client told her that her missing sense of smell could be an early

sign of Parkinson's. The results revealed she carried the LRRK2

mutation. She subsequently got diagnosed with prodromal

Parkinson's, which means the disease can be detected in her brain

but hasn't yet seriously affected her movement.

Ms. Winter-Evans said she would be an eager participant in a

clinical trial targeting LRRK2. "The importance of finding a cure

far outweighs my illusion of privacy," she said.

Corrections & Amplifications 23andMe has analyzed the DNA of

more than eight million people. An earlier version of this article

and an accompanying graphic incorrectly said the company has

analyzed the DNA of more than five million people. In addition,

GlaxoSmithKline is among the drug makers working with UK Biobank.

An earlier version of the graphic didn't show that connection.

(July 23, 2019)

Write to Denise Roland at Denise.Roland@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

July 24, 2019 02:47 ET (06:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

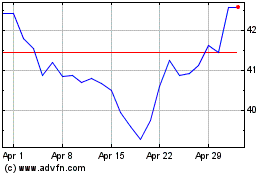

GSK (NYSE:GSK)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

GSK (NYSE:GSK)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024