By Sharon Terlep and Jaewon Kang

In some towns, it's getting harder to pick up your

blood-pressure pills with that gallon of milk and rotisserie

chicken.

Hundreds of regional grocery stores in cities from Minneapolis

to Seattle are closing or selling pharmacy counters, which have

been struggling as consumers make fewer trips to fill prescriptions

and big drugstore chains tighten their grip on the U.S. market.

Grocery pharmacies are getting hit on several fronts, analysts

and the companies say. They are too small to wrest competitive

reimbursement rates on drugs, they aren't connected to big medical

networks or insurers, and they generally lack walk-in clinics and

other health services that draw many customers to CVS and Walgreens

locations.

"Our establishment had a community feel, it wasn't overly busy

so we got to really care for our customers," said Phillip Breker,

who managed a now-closed pharmacy at Lunds & Byerlys, a

Minneapolis-area grocery chain. "I also saw the numbers in the back

end and how that soured in the last 10 years. The company made the

right decision."

Grocery pharmacies are the latest casualty of industry

consolidation that has for years been forcing mom-and-pop

drugstores to close. Even some big players have rethought the

market. Target Corp. sold off its pharmacy business to CVS Health

Corp. five years ago.

Supermarkets have viewed pharmacies as a tool to draw shoppers

in. Fueled by easy profits and relatively low startup costs,

legions of stores added pharmacy counters in the 1980s and 1990s.

Grocery drugstores proliferated to account for roughly 14% of

retail pharmacy prescriptions, according to the National

Association of Drug Stores.

The number of grocery pharmacies declined for the first time in

years in 2017, the latest year for which data is available, to

9,026, down from 9,344 in 2016.

Consumers are increasingly getting 90-day supplies of their

medicines or getting prescriptions delivered in the mail. Those

trends are resulting in a decline in foot traffic to supermarket

pharmacies, which were typically located at the back of stores.

Meantime, profits are ever harder to come by as the health-care

industry consolidates.

CVS and Walgreens Boots Alliance Inc., the nation's biggest

players, contributed more than 40% of U.S. prescription revenues in

2018, according to Drug Channels Institute, which provides research

on the drug supply chain.

The chains, which now either own or have partnerships with the

biggest insurers and pharmacy-benefit managers, are able to secure

better deals on drug costs that largely shut out the industry's

smaller players. Pharmacy-benefit managers serve insurers and other

clients by choosing which medicines to cover and pushing for lower

prices from drugmakers and sellers.

CVS and Walgreens also are working to transform drugstores into

health-care hubs, offering services from blood testing to

chronic-disease management.

"The biggest companies in health care now have pharmacists and

doctors, they own medical practices, and they own urgent-care

clinics," Baird analyst Eric Coldwell said. Grocery pharmacies

"have none of this. They have a store to go into to buy lemons and

bread."

The tougher conditions come as the entire drugstore industry

copes with a shift to online shopping and shrinking profits in

prescription medicines, which often disproportionately affect

smaller players.

Walgreens and CVS have closed or are closing more than 300

underperforming stores, while Rite Aid Corp., the No. 3 U.S. chain,

is struggling to turn itself around after regulators blocked a

merger with Walgreens in 2017.

Raley's Supermarkets, a West Sacramento, Calif., chain of about

120 stores, last year shut down a third of its roughly 100

pharmacies and transferred prescriptions to nearby Walgreens, CVS

and Rite Aid stores. Those grocery pharmacies had low prescription

rates, were losing money and didn't merit high operating and labor

costs, according to Raley's.

"There is the benefit of having a pharmacy relative to the

grocery-sale lift and the convenience factor of having both in the

store, but the economics do not work," said Keith Knopf, chief

executive of Raley's.

Profitability for grocers has become harder to achieve in recent

years, and pharmacies play a less important role today in

attracting customers, Mr. Knopf said. Raley's is cutting hours for

the remaining pharmacies to improve profits and create efficiency.

Pharmacies make up roughly 20% of Raley's total sales.

Many grocers still view pharmacies as a key part of their

business. Kroger Co., the biggest U.S. supermarket chain, said its

pharmacy business is expected to improve this year after

lower-than-expected profits in 2019. Kroger has said pharmacy

shoppers tend to be more loyal, spending three times as much as

nonpharmacy customers.

"We've been able to connect the relationship with food and are

starting to build out new revenue streams," Kroger finance chief

Gary Millerchip said at an investor meeting in November.

Lunds & Byerlys, the Minnesota chain, shut all 14 of its

supermarket pharmacies last year. At each location, it posted a

sign that has become increasingly common: "The pharmacy is now

closed. Your prescription records have been transferred to

Walgreens."

Mr. Breker, the pharmacy manager, now works for Walgreens at a

location in a nearby town. "I literally cried at the counter with

dozens of people," he said. "They felt a loss here."

Write to Sharon Terlep at sharon.terlep@wsj.com and Jaewon Kang

at jaewon.kang@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

January 26, 2020 05:44 ET (10:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

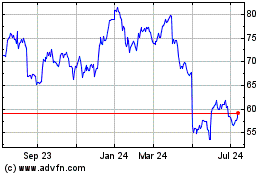

CVS Health (NYSE:CVS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

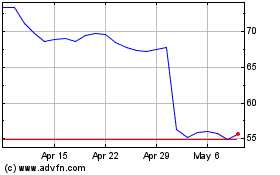

CVS Health (NYSE:CVS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024