By Robbie Whelan and Santiago Pérez

MEXICO CITY -- With global supply chains in disarray amid the

U.S.-China trade war and the coronavirus pandemic, Mexico might

seem a logical winner if U.S. companies decide they want to

diversify away from China and make some products closer to

home.

Mexico clinched a new trade deal with the U.S. and Canada last

year and has now replaced China as the U.S.'s largest single

trading partner.

"These trade frictions between the U.S. and China and the

coronavirus should definitely be a godsend to Mexico," said Alberto

Ramos, chief Latin America economist at Goldman Sachs Group Inc.

"Mexico would be extremely well positioned to capture part of that

trade."

While Mexico might benefit in the long run, there are plenty of

reasons to be cautious about predicting a flood of companies

heading there. For starters, the data doesn't suggest Mexico is

enjoying an investment boom.

Foreign direct investment in Mexico fell 5.2% last year compared

with 2018, according to preliminary government figures, while the

economy shrank by 0.1% in 2019. Mexico's exports to the U.S. have

grown modestly over the past year and a half, far slower than those

from countries like Vietnam.

Supply-chain experts point to several factors. Despite the new

U.S.-Mexico-Canada trade deal, the Trump administration could upend

trade relations at any time.

Adding to the uncertainty are the economic policies of Mexico's

nationalist President Andrés Manuel López Obrador and increasing

violence that has turned parts of the country into no-go areas.

"I don't think trade relations are sufficiently settled to boost

long-term investment in Mexico as a hub," said Gustavo Rangel,

chief Latin America economist at ING Financial Markets. "Clearly

China is a riskier bet, but it's unclear to what extent that

benefited Mexico."

Apart from a jump in automotive exports in 2018, Mexico's

manufactured exports haven't responded to the U.S.-China trade

tensions with the expected surge, according to economist Brad

Setser, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations.

Meantime, annual growth in U.S. imports of manufactured goods

from Vietnam jumped to more than 40% in early 2019, and remained

above 30% through the end of the year, according to Census Bureau

data. Monthly U.S. imports of manufactures from Mexico grew around

10% a month in early 2019 but were falling at the end of the year,

while U.S. import growth from China contracted sharply all

year.

"It's impossible to make an argument in a statistical sense that

there has been a large visible shift to Mexico," Mr. Setser

said.

A big reason manufacturing might be sticking in Asia rather than

relocating is that supply chains in industries like electronics are

deeply entrenched, and Mexico lacks a deep supply chain in areas

outside the automotive sector, Mr. Setser said. Overall costs in

Asia are also still low.

Mexico, however, could still benefit over the longer term.

Manufacturing wages in Mexico are lower than in China, and the

country isn't only next door to the U.S., but also shares cultural

ties and similar time zones with U.S. firms.

In January, Jose Luis Bernal, Mexico's ambassador to China, said

that at least three Chinese auto firms, including car maker

Changan, electric-car manufacturer BYD and assembly and auto parts

firm JAC Motors, planned to begin or expand production in Mexico in

the next year.

And last year, sports-camera maker GoPro Inc. moved most

production of its U.S.-bound cameras from China to the Mexican city

of Guadalajara. At the time, a GoPro executive said the decision

"supports our goal to insulate us against possible tariffs as well

as recognize some cost savings and efficiencies."

Mr. López Obrador's policies are also undermining Mexico's

foreign-investment potential, observers say. In his first year in

office, he canceled the country's biggest public-works project, a

partially built Mexico City airport, and halted any new oil

auctions for private oil firms.

The latest private-sector casualty could be Constellation Brands

Inc., which brews Mexico's venerable Corona beer for U.S. drinkers.

The López Obrador administration is organizing a referendum on

March 21 in the border city of Mexicali to decide whether the beer

maker, one of Mexico's largest foreign investors, can complete

construction of a $1.4 billion plant, after community groups raised

objections about its intensive water consumption. The cancellation

of such a large-scale project would send a wrong signal to foreign

investors, executives say.

Mexico's lagging foreign investment is a long-term trend.

Foreign direct investment averaged 1.6% of Mexico's gross domestic

product over the past decade, compared with an average of 2.2% of

GDP from 1995 to 2007, estimates Sergi Lanau, deputy chief

economist at the Institute of International Finance in Washington,

D.C.

Out-of-control criminal violence doesn't help. Last year was the

bloodiest in Mexico's recent history, with 35,588 people murdered,

according to government estimates.

In 2018, the American Chamber of Mexico, an association of

business groups, polled 415 of its members on security issues and

found that 25% of them believed their businesses were less safe

than the previous year. Of those, 71% attributed the decline in

security to the rise of organized crime. More than 14% of

businesses questioned said they had suspended operations in certain

Mexican states because of rising violence.

--David Luhnow and Anthony Harrup contributed to this

article.

Write to Robbie Whelan at robbie.whelan@wsj.com and Santiago

Pérez at santiago.perez@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

March 15, 2020 07:14 ET (11:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

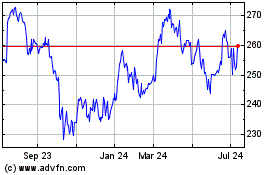

Constellation Brands (NYSE:STZ)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

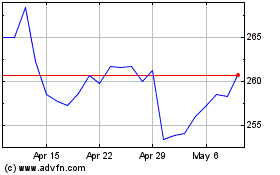

Constellation Brands (NYSE:STZ)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024