By Orla McCaffrey

Banks are paying a pittance on deposits, but customers don't

seem to care.

Some banks are slashing deposit rates. Others are keeping

already-low rates at next to nothing, sometimes 0.01%. But

customers keep stashing cash at banks anyway.

Big banks can afford to be stingy because they already are awash

in deposits. Total deposits at U.S. commercial banks have swelled

to about $15.9 trillion, up from about $13.2 trillion at the start

of the year, according to the Federal Reserve.

The biggest banks, such as JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Bank of

America Corp., generally keep their rates low no matter what is

happening in the rest of the economy. They already have mountains

of deposits, as well as loyal customers who bank with them not for

high deposit rates but for ubiquitous branches, flashy apps or

because their paychecks and bills are already tied to their

accounts there.

Online-focused firms including Ally Financial Inc. and Goldman

Sachs Group Inc.'s Marcus, on the other hand, have touted their

high rates over the past few years as a way to attract deposits.

But even those banks are now cutting rates. Ally, Marcus and

Capital One Financial Corp., for example, have dropped their

deposit rates from about 1.6% to around 0.5% over the past eight

months.

Banks typically cut deposit rates when the Fed lowers short-term

interest rates. The Fed slashed rates dramatically in March,

trimming 1.5 points from its benchmark rate during two back-to-back

cuts. The online-focused banks have been cutting ever since.

Some brinkmanship is involved. Banks choose when to raise or cut

their deposit rates, but they are influenced by the Fed and by each

other. When the Fed lowers rates, banks -- especially the online

players -- generally want to reduce their rates too, but nobody

wants to be first for fear of turning off customers.

Big banks also have more deposits than they know what to do with

-- a more consistent catalyst for deposit-rate cuts this year,

analysts said.

Deposits began flooding into commercial banks in the spring,

when the economy shut down to battle the coronavirus pandemic. Loan

demand at many banks stalled at the same time, meaning banks have

fewer and less lucrative opportunities for putting their deposits

to work.

The spring surge was driven primarily by bank customers with

balances under $2,500, according to Novantas, a financial-services

research firm. They increased their total deposits by 66% from

mid-April to late May, compared with just 1% for higher-tier

customers, or those with deposits of at least $5,000.

Many lower-balance customers had more cash on hand after the

government rolled out coronavirus relief including expanded

unemployment benefits and one-time stimulus checks.

That began to change in early June, when higher-balance

customers began depositing at higher volumes. Higher-tier customers

have increased their balances by an average 8% over the past five

months, compared with just 2% for those with lower balances.

There are signs that the sea of deposits is, if not shrinking,

at least stabilizing. The overall rate of deposit growth has

flattened since its spring peak, though deposits remain at record

levels.

The level of reserves kept by lenders at their regional Fed

banks has ballooned alongside bank deposits. Banks stash deposits

at the Fed when they have more than enough to fund operations

including lending.

Regions Financial Corp. had more than $10 billion parked at the

Fed in the third quarter, up from its typical $1 billion to $2

billion, Chief Financial Officer David Turner said.

"Deposit growth has been off the chart but there's not a lot of

loan demand out there," he added.

Already-low deposit rates at bricks-and-mortar banks have

trended downward along with those at online banks. The average rate

on savings accounts at U.S. banks stands at 0.08%, down from 0.1%

in early spring, according to Bankrate.com, a personal-finance

website.

"Banks are trying to get rid of deposits," said Gary Zimmerman,

founder of MaxMyInterest, which matches bank customers with

higher-yield accounts. "The only way they know how to do that is

lowering rates and hoping people go away."

But for many people, money stashed in a savings account

represents an important protection against potential financial

hardship. Easy access to that money outweighs the fact that they

are being paid peanuts in interest.

Andrew Frisbie, executive vice president for consumer pricing at

Novantas, said the pandemic had made many customers more interested

in saving money for an emergency.

"The pandemic was the ultimate rainy day," he said.

Some customers, though, are the exception: They are happy to go

to the trouble of moving their money in search of higher

returns.

Ray Gustavis, a trial attorney in Jackson, Miss., decided to

move about $7,500 from Ally in July, when the bank cut its rate

from 1.10% to 1%.

Ally said it is "committed to providing tools that help people

make smarter money decisions -- no matter what the

environment."

Still, Ms. Gustavis decided to split the money in her Ally

account between the stock market and an account at another bank

that offered a slightly higher rate.

"It just made no sense to keep my money there anymore," Ms.

Gustavis said. "It might as well be put under my bed."

Write to Orla McCaffrey at orla.mccaffrey@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

November 12, 2020 05:44 ET (10:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

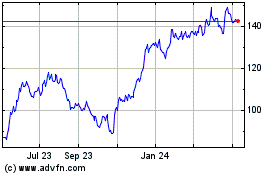

Capital One Financial (NYSE:COF)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

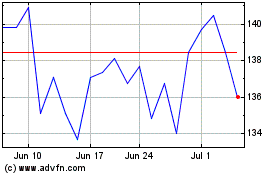

Capital One Financial (NYSE:COF)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024