By Andy Pasztor and Andrew Tangel

House Democrats issued a sharply worded report revealing new

details of how the combination of Boeing Co. design errors, lax

government oversight and lack of transparency by the plane maker

and regulators set the stage for two fatal 737 MAX crashes.

The 238-page document, written by the majority staff of the

House Transportation Committee, calls into question whether the

plane maker or the Federal Aviation Administration has fully

incorporated essential safety lessons, despite a global grounding

of the MAX fleet since March 2019.

After an 18-month investigation, the report, released Wednesday,

concludes that Boeing's travails stemmed partly from a reluctance

to admit mistakes and "point to a company culture that is in

serious need of a safety reset."

"We have learned many hard lessons as a company from the

accidents of Lion Air Flight 610 and Ethiopian Flight 302, and from

the mistakes we have made," Boeing said in a written response to

the report, referring to the two fatal MAX crashes. The

Chicago-based aerospace giant added: "We have been hard at work

strengthening our safety culture and rebuilding trust with our

customers, regulators, and the flying public."

The findings released Wednesday also questioned whether pending

changes inside the FAA would be sufficient to end what the report

describes as fundamentally inadequate government reviews of new

aircraft designs. Engineering and management errors on the MAX,

according to the report, reflect a flawed approval process in which

agency managers often undercut the authority of lower-level FAA

engineers, giving industry undue influence over the process.

The report blames "grossly insufficient oversight by the FAA,"

leaving the agency unable to appropriately meet its

responsibilities and ensure passenger safety.

Rep. Peter DeFazio, the Oregon Democrat who is the committee's

chairman, said the 737 MAX saga highlights the need for major

changes to U.S. air-safety regulation. "The problem is: It was

compliant and not safe, and people died," Mr. DeFazio said of the

aircraft in a press briefing Tuesday. "Obviously, the system is

inadequate."

Responding to the report, the FAA said it is "committed to

continually advancing aviation safety and looks forward to working

with the committee to implement improvements identified in its

report," adding that voluntary initiatives already are under way

based on lessons learned. The statement added that its focus is on

"improving our organization, processes and culture." The agency

reiterated that it has mandated design changes to the MAX and

"continues to follow a thorough process, not a prescribed timeline,

for returning the aircraft to service."

The report provides more specifics, in sometimes-blistering

language, backing up preliminary findings the panel's Democrats

released six months ago, which laid out a pattern of mistakes and

missed opportunities to correct them. Misfires of an automated

flight-control system, called MCAS, overpowered pilots and led to

two MAX crashes in less than five months that took 346 lives.

Fresh details in the report, however, show that various Boeing

employees recognized and repeatedly flagged some of those hazards

years before the FAA in 2017 certified the MAX as safe to carry

passengers, though their warnings failed to prompt high-priority

reviews by either the company or the agency.

Republican staffers participated in some interviews, including

with two high-ranking Boeing executives who defended the plane

maker's design process. But none of the panel's GOP members signed

off on the report.

Senior Republicans on the committee disputed the Democrats' call

for an overhaul of U.S. aircraft certification, dismissing the

report as partisan. "Expert recommendations have already led to

changes and reforms, with more to come," they said in a statement

setting the stage for debate over an air-safety bill the

committee's Democrats are expected to introduce in coming

weeks.

In one section, the Democrats' report faults Boeing for what it

calls "inconceivable and inexcusable" actions to withhold crucial

information from airlines about one cockpit-warning system, related

to but not part of MCAS, that didn't operate as required on 80% of

MAX jets. Other portions highlight instances when Boeing officials,

acting in their capacity as designated FAA representatives, part of

a widely used system of delegating oversight authority to company

employees, failed to alert agency managers about various safety

matters.

The longest portion of the document details previously

undisclosed safety concerns raised inside Boeing by lower-level

employees about the design and vulnerabilities of MCAS itself,

concluding those questions "were inadequately resolved or

dismissed."

In June of 2016, about a year before the FAA certified the MAX's

safety, a Boeing engineer sent a colleague an email that referred

to a company test pilot's difficulty leveling the plane's nose due

to repetitive MCAS activations.

After the engineer questioned whether the pilot's maneuvering

difficulty amounted to a safety issue, the colleague responded it

didn't, but noted that in such a situation, pilots could "find

themselves in a large mistrim," meaning the plane's nose could be

sharply pointed down. That was exactly the scenario that played out

in each MAX crash, with cockpit crews unable to regain control

after the planes' noses were forced downward by repeated, erroneous

MCAS activations.

In another exchange, a Boeing employee asked how MCAS would

react to faulty sensor data--which accident investigators would

later identify as a precipitating factor in both fatal crashes--but

the issue was dismissed by a colleague.

The report said the internal Boeing design concerns weren't

sufficiently resolved or addressed.

The House panel also highlighted internal Boeing documents

spanning 2015 to 2018 that noted a company test pilot's finding

that a slow reaction to an MCAS misfire--one taking longer than 10

seconds--could result in catastrophe.

The report said several Boeing employees working on behalf of

the FAA didn't share the test pilot's finding with the agency.

Boeing has said it relied on industrywide safety principles to

assume pilots would be able to respond appropriately to an MCAS

misfire in four seconds.

In its statement responding to the report, Boeing highlighted

steps it has taken in the wake of the MAX saga, which has cost it

billions of dollars, on top of lost revenue and a drop in

stock-market value, and significantly damaged its reputation. "We

have made fundamental changes to our company," Boeing said, noting

"change is always hard and requires commitment" and adding it is

dedicated to doing that work.

Delving into the period between the two crashes, the report said

both the FAA and Boeing "seemed more intent on justifying their

previous mistakes than in fully confronting the safety issues." And

committee investigators presented a picture of the FAA's safety

chief, Ali Bahrami, as divorced from day-to-day concerns about the

MAX. According to the report, Mr. Bahrami told the investigators in

an interview that he hadn't seen Boeing's bulletin reminding pilots

of an emergency procedure days after the first MAX accident in

October 2018.

Mr. Bahrami also told House staffers he wasn't familiar with an

internal FAA risk assessment after the first crash, which projected

15 more fatal crashes over the decadeslong lifetime of the MAX

fleet if Boeing didn't add safeguards to MCAS, the report said.

"I'm not familiar with the details of it," Mr. Bahrami told the

committee's investigators in a December 2019 interview, according

to the report. Mr. Bahrami acknowledged he decided fixes to MCAS

could wait while the plane kept flying, because he and other FAA

officials believed pilots would be able to intervene to avoid a

crash. Echoing Boeing's initial defense of its MCAS design after

the first crash, the FAA official said "pilots are part of the

system, and we rely on pilots to do certain things."

The transcript of Mr. Bahrami's interview with House

investigators shows he said he didn't recall any conversations with

Boeing counterparts in the nearly five months between the two

accidents. The report, however, cites emails showing he scheduled a

call with a high-ranking Boeing executive to discuss the crash in

Indonesia, though it wasn't clear to the committee's investigators

whether the conversation took place. The FAA had no specific

comment on Mr. Bahrami's testimony.

But in a message sent to FAA staff Tuesday, which was reviewed

by The Wall Street Journal, Mr. Bahrami alerted them to the House

panel's findings. "While the report is critical of both Boeing and

the FAA, it offers valuable insights into how we can improve,"

according to the message. After reiterating agency initiatives he

supports, Mr. Bahrami's message also urged employees to "work

together to further enhance our safety processes."

Write to Andy Pasztor at andy.pasztor@wsj.com and Andrew Tangel

at Andrew.Tangel@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

September 16, 2020 05:14 ET (09:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

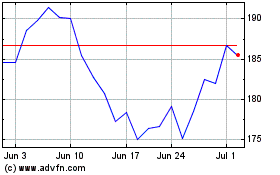

Boeing (NYSE:BA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Boeing (NYSE:BA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024