By Andy Pasztor

Boeing Co. is grappling with still another software problem that

has cropped up in its effort to fix its 737 MAX aircraft, adding to

technical issues that have complicated and delayed the grounded

fleet's return to service over many months.

The latest glitch, which Boeing said Friday it was working to

correct, prevents the jet's flight-control computers from powering

up and verifying they are ready for flight, according to industry

and government officials.

"We are making necessary updates and working with the FAA on

submission of this change, and keeping our customers and suppliers

informed," a Boeing spokesman said.

Before the problem was discovered last week, according to people

briefed on the details, the company and the Federal Aviation

Administration were slated to conduct a key certification flight by

the end of this month. But at this point, these people said, that

date increasingly looks like it will slip into at least

February.

The length of the delay will largely depend on how long it takes

Boeing engineers to address the problem and verify its elimination,

though coordination with international regulators and other factors

could complicate the process.

It also isn't clear how much of a delay the problematic software

could create in the end since various other regulatory steps

affecting the MAX's return, including finalizing pilot-training

requirements, are running late and remain in limbo.

U.S. carriers already have pulled MAX jets from their schedules

through early June, though industry and government officials

project that the planes could start making demonstration flights

with airline executives on board weeks before that.

The MAX fleet was grounded in March, not long after the second

of two crashes that killed a total of 346 people.

The software problem occurred as engineers were loading updated

software -- including an array of changes painstakingly developed

over roughly a year -- into the flight-control computers of a test

aircraft, according to one person briefed on the details.

A software function intended to monitor the power-up process

didn't operate correctly, according to this person, resulting in

the entire computer system crashing. Previously, proposed software

fixes had been tested primarily in ground-based simulators, where

no power-up problems arose, this person said.

The revised software is intended to fix an automated

flight-control system called MCAS that led to the two fatal

crashes, in 2018 and 2019. The system, new on the MAX, misfired in

a way that repeatedly and forcefully pushed the planes' noses down,

overpowering pilot commands and ending in fatal dives. The company

has been developing revised software intended to make the system

less prone to such misfires and easier for pilots to

counteract.

Boeing also has increased redundancy by having the plane's dual

flight-control computers operate throughout each flight, a change

that industry and government officials said has entailed more

software changes than Boeing initially anticipated.

FAA and Boeing officials were in the midst of analyzing

prospects for the latest software revisions when Steve Dickson, the

agency's administrator, met with newly installed Boeing chief Dave

Calhoun early this week. Neither government nor Boeing officials

have commented on that session.

In addition to completion of the software fixes, the MAX's

return to service is subject to test flights by a representative

group of international airline pilots, along with public comments

on the details of extra training for cockpit crews.

The FAA also has to approve changes to operating and training

manuals, endorse revised emergency procedures and sign off on

maintenance and inspections of planes that have been in storage,

some for many months.

Numerous foreign regulators have signaled they won't approve

resumption of passenger flights until their own engineering and

pilot-training reviews are finished.

Nevertheless, the coming certification flight is widely

considered the next major step to ease the MAX crisis, which has

cost Boeing and the global airline industry billions of dollars and

disrupted flight schedules around the world.

If resolving the most recent software errors takes longer than a

few weeks, the MAX's overall return to service timeline could take

another significant hit.

Initially, Boeing and many of its airline customers expected

that a software fix dealing solely with the shortcomings of MCAS

could be rolled out fairly quickly.

After a Lion Air jet went down in Indonesia in October 2018, the

plane maker and FAA experts projected the necessary changes could

be made, tested, approved and implemented world-wide in seven

months. But as U.S. and international regulators delved into other

aspects of the flight-control computers, new safety concerns arose

that prompted months of further analysis and testing.

During the summer, changes to emergency procedures and issues

regarding reliability of computer hardware prompted more studies

and software tweaks. Months later, regulators balked at what they

considered Boeing's failure to promptly provide data backing up

software changes, prompting another slowdown in the process.

The MAX's return also faces significant challenges when it comes

to changes in software used in flight-simulators to train

pilots.

Such devices are in short supply world-wide, and some of those

that are available have somewhat different software configurations

depending on when they were updated and certified by regulators. As

a result, some airlines are concerned that pilots trained on early

versions may have to be recalled and run through follow-up

simulator sessions to comply with eventual safety mandates.

Write to Andy Pasztor at andy.pasztor@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

January 17, 2020 18:56 ET (23:56 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

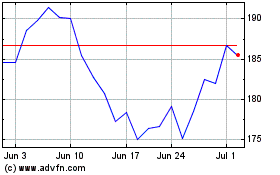

Boeing (NYSE:BA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Boeing (NYSE:BA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024