By Asjylyn Loder

The amount of money in fixed-income exchange-traded funds passed

$1 trillion last month, an ascendance that has reshaped the market

where countries and companies raise money to pay their bills.

Just 20 years ago, bond ETFs didn't even exist. The bond market

was a largely sleepy enterprise that had long resisted the

high-tech upheaval that transformed the way stocks are bought and

sold. Even today, the biggest bond trades can take hours, or even

days, while billions of dollars in stocks change hands in

seconds.

But from that sleepiness came opportunity.

Firms like BlackRock Inc., Invesco Ltd. and State Street Corp.

put millions behind building a new class of investment: the bond

ETF. The idea was to straddle two disparate markets by wrapping

slow-to-trade bonds in lightning-fast funds. Like a mutual fund,

ETFs bundle together hundreds of bonds into a one-stop-shop ticker.

Unlike mutual funds, ETFs trade all day on a stock exchange just

like shares of Apple Inc. or Bank of America Corp.

Today, the product has never been more popular. All types of

investors -- from pension funds to insurers to retirees -- trade

them daily.

The biggest proponents of bond ETFs say their growth has added

much-needed speed to the sluggish business of bond trading. This

allows investors to move money swiftly when market sentiment

turns.

Skeptics argue that bond ETFs are a dangerous combination. They

say the product could accelerate a selloff if fleeing investors

flood the debt market with more sell-orders than it can handle.

As this debate continues, bond ETFs just get bigger and bigger.

Even the banks and hedge funds that once viewed them as the

competition are now big customers.

"Two or three years ago, a bank wouldn't take our calls about

fixed-income ETFs," said Bill Ahmuty, head of fixed income for

State Street's SPDR ETF business. "Now they're calling us."

One of the biggest hurdles to creating bond ETFs was the

complexity of the fixed-income market. A single company can have

dozens or even hundreds of outstanding notes, each with different

interest rates, due dates and terms. Many transactions are still

handled by phone and instant messages, and some bonds don't trade

for days, or even months.

Thin trading in some of these notes makes it particularly hard

to figure out what debt is worth in real time, but ETFs must post

the value of their portfolio every 15 seconds.

To make this work, the creators of the first fixed-income ETFs

estimated the value based on other information, like derivatives

prices, interest rates or transactions in similar bonds. Since

BlackRock bought iShares from Barclays PLC in 2009, the company has

devoted even more resources to developing and trading bond

ETFs.

BlackRock today manages about $6.5 trillion, up from $1.3

trillion a decade ago.

Earlier this month, The Wall Street Journal sat down with one of

the biggest beneficiaries of the bond ETF boom: Rob Kapito,

president of BlackRock. When asked about the liquidity-crunch

criticism bond ETFs most often get, Mr. Kapito responded with an

eye roll.

Mr. Kapito made little effort to conceal his derision for

armchair alarmists.

"A lot of your colleagues have been trying to find a fault with

this thing," Mr. Kapito said. "It's a pent-up desire that hasn't

been fulfilled, because it actually works."

Mr. Kapito spent much of his early career trading bonds, as did

BlackRock Chief Executive Larry Fink. Its iShares ETF business was

the first to introduce fixed income ETFs in 2002.

Today, roughly half of the assets in fixed-income ETFs is in

iShares funds. Investors in its U.S. fixed-income ETFs pay more

than $600 million a year in fees, almost 20% of iShares domestic

haul, according to Morningstar estimates.

That is a pittance compared with the potential BlackRock is

banking on. Mr. Kapito points out that ETFs own less than 1% of the

world's debt, leaving more than $100 trillion that has yet to be

repackaged into ETFs. It took 17 years to raise the first $1

trillion, but BlackRock predicts fixed-income ETFs will double in

size within the next five years.

"We believe that this is going to be a huge growth area for the

firm," Mr. Kapito said.

Even so, critics remain concerned that the growth of

fixed-income ETFs could distort bond pricing.

Caitlin Dannhauser, an assistant professor of finance at

Villanova University, says her research found that bonds that are

more exposed to an ETF exodus take a bigger hit during bouts of

turbulence than those that aren't. Battered bond prices could make

it harder and more expensive for firms to borrow money.

"It could be really disruptive for a company that has a lot of

bonds exposed to ETF outflows," Ms. Dannhauser said.

Those fears haven't slowed the growth of the industry.

Fixed-income ETFs raised almost $33 billion in June, on track for

their best month in history.

The ETFs are especially popular when there is fast-moving market

news, and bond trading is too slow to keep up. Earlier this month,

when the Federal Reserve hinted that it would lower interest rates

later this year, the oldest iShares corporate-debt ETF had one of

its busiest trading days on record, with more than $3 billion

changing hands.

To receive our Markets newsletter every morning in your inbox,

click here.

Write to Asjylyn Loder at asjylyn.loder@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

July 01, 2019 09:21 ET (13:21 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

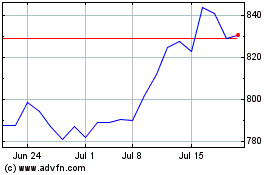

BlackRock (NYSE:BLK)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

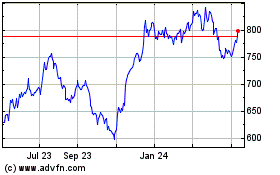

BlackRock (NYSE:BLK)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024