By Richard Rubin and Jared S. Hopkins

This article is being republished as part of our daily

reproduction of WSJ.com articles that also appeared in the U.S.

print edition of The Wall Street Journal (August 2, 2019).

Inversions are starting to revert.

When Mylan moved its corporate address to the Netherlands in

2015, the pharmaceutical company joined a wave of corporate

inversion deals aided by tax advantages of a non-U.S. address. Now,

Mylan's address is coming back to the U.S. through a merger deal

this week with part of Pfizer Inc., a sign that the 2017 tax law is

rendering these moves less attractive than they once were.

The deal comes a month after Allergan PLC -- another inverted

pharmaceutical company, based in Dublin -- announced its return to

a U.S. parent through a sale to AbbVie Inc.

On balance, say tax lawyers and analysts, foreign addresses

still confer a slight tax advantage.

But after the U.S. corporate tax cuts in the 2017 law, the edge

is small enough that it might not be worth reputational and

political costs.

Those changes might deter new inversions and cause inverted

companies to retake U.S. addresses if other business reasons

warrant such a move. Inversion deals were particularly hot from

2012 to 2015, as companies such as Eaton Corp. and Medtronic PLC

took foreign addresses.

The moves generated political blowback as lawmakers criticized

companies as abandoning the U.S. The dust-up led to new regulations

and provided some of the impetus for the 2017 tax-code rewrite.

"Transactions that historically would have been structured as

inversions are no longer being structured that way, even when the

opportunity to do it is clearly there," said Robert Willens, a New

York tax analyst. "Before, there was such a clear economic

advantage to structuring as an inversion that you were willing to

withstand the negative aspects."

Earlier this decade, companies had strong incentives to take

non-U.S. addresses. U.S. companies owed the full 35% tax rate on

their world-wide income, though they got credits for foreign taxes

and deferred the U.S. layer until they repatriated money.

Foreign-based companies didn't face that second tax layer. And

they could use a technique called earnings stripping, loading U.S.

operations with deductible expenses and pushing profits into

lower-taxed jurisdictions.

Through mergers, companies such as Allergan, Mylan, Medtronic

and Johnson Controls PLC moved tax addresses abroad. The companies

were often managed from the U.S.

"It was always a fiction that they were foreign," said Steve

Wamhoff, director for federal tax policy at the Institute on

Taxation and Economic Policy, a liberal group critical of corporate

tax avoidance.

Obama administration regulations curbed some benefits. Then, the

2017 law cut the U.S. corporate tax rate to 21% from 35%, reducing

incentives for profit shifting and using foreign-parented

companies.

"The Trump administration's response to this whole situation was

to cut corporate taxes enough that corporations don't really need

to try that hard to avoid them," Mr. Wamhoff said.

The law also aimed at earnings stripping by adding a tax on

certain cross-border transfers within companies.

"It's too early to say definitively that the playing field is

level, but it is more level today than it was," said Bret Wells, a

law professor at the University of Houston.

Because companies changed addresses without necessarily moving

jobs or operations, inversions had limited economic effects. But

the moves reduced federal revenue and disadvantaged U.S. companies

competing against inverted firms.

In this week's deal, Pfizer's off-patent drug division will

merge with Mylan, best known for the EpiPen emergency allergy

treatment. The new, yet-unnamed company is expected to be among the

biggest sellers of generic and off-patent medicines, with more than

$19 billion in yearly sales.

Favorable corporate tax conditions resulting from the 2017 law

contributed to the decision to domicile the new company in the

U.S., according to people familiar with the merger. But an

important reason was also Delaware's attractive

corporate-governance rules for shareholders, according to Mylan and

Pfizer.

"That's a very important part of the investment thesis," Albert

Bourla, Pfizer's chief executive, said in an interview.

Analysts and investors had criticized Mylan's Dutch governance

structure. Mylan's decision to become a Dutch corporation through

an acquisition while keeping its headquarters in Pittsburgh was

seen as defensive. Afterward, Mylan engaged in a takeover battle

with rival Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd. Mylan fended that

off after setting up a foundation, called a stichting in Dutch,

that triggered a Dutch variation on a poison pill.

Mylan's chairman, Robert J. Coury, told analysts this week that

governance played a greater role than tax for Mylan's exit from the

U.S. At the time of the inversion he endorsed inverting and its tax

benefits in a USA Today commentary.

Allergan referred comment to AbbVie, which said in a written

statement that remaining a U.S.-incorporated company was the most

appropriate structure for the company.

Under the new tax system, there are still benefits to a non-U.S.

address, because it can help companies avoid a new minimum tax on

U.S. companies' foreign income. Also, the parent's address is only

part of tax calculations. Some companies can still reduce U.S.

taxes by reporting profits abroad or investing in foreign

factories.

--Jonathan Rockoff contributed to this article.

Write to Richard Rubin at richard.rubin@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

August 02, 2019 02:47 ET (06:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

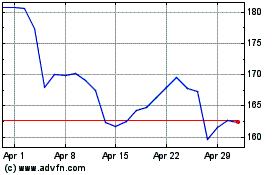

AbbVie (NYSE:ABBV)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

AbbVie (NYSE:ABBV)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024