The Big Challenge for Policy Makers: Policing American Tech Giants

June 03 2019 - 7:36AM

Dow Jones News

By Jacob M. Schlesinger

Free services are good for consumers. Monopolies tend to be bad

for them. The big tech platforms have elements of both--a

combination that is vexing policy makers around the world as they

struggle to figure out how best to police American technology

behemoths and their unusual business models.

The latest sign of escalating scrutiny: The Justice Department

is laying the groundwork for an antitrust investigation of Google.

That isn't surprising. On the surface, the Alphabet Inc. unit has

traits that would traditionally raise concerns about stifled

competition squelching choices for consumers. The same could be

said for Facebook Inc., Amazon.com Inc. and Apple Inc.

They all have dominant market shares in their sectors--from

search to social media, e-commerce, online advertising and

smartphone apps--and are protected by practices and conditions that

make it hard for new rivals to challenge them.

And yet they don't fit neatly into the old formulas that signal

harm from such power: higher prices and less choice for consumers.

On the contrary, these companies offer many of their core products

to customers for no charge. And they have vastly expanded the

ability of consumers to search, compare and buy a newly broad range

of products from all over the world with a quick click, search, or

download.

Big tech "creates novel complexities and considerations,

particularly a concern that the digital platform may be a unique

combination of economic forces that require both new analysis and

new public policy," said a report issued in mid-May by a group of

scholars at a University of Chicago conference dedicated to

debating how to apply antitrust to the 21st-century economy.

The Chicago meeting followed exhaustive studies on the subject

completed in recent months by governments around the world,

including the U.K., the European Commission and Australia. All

reached similar conclusions about the evolving nature and impact of

competition in the digital world.

One common argument is that consumers are facing myriad harms

even as they now enjoy free services that used to cost money, like

searching for information, using maps and getting directions,

communicating with friends and having goods shipped to their

homes.

Many economists say consumers do pay for all of these services,

not with cash but by providing the tech companies with valuable

information about their personal lives as well as shopping and

search habits. Those companies in turn convert that data into big

profits by selling it to advertisers and other users. These

economists say that in a more competitive market, the real

free-market price could be lower than it is. Consumers, they

suggest, might be paid for that data.

"Although accessing services for free may appear to be an

attractive proposition, this zero-price may in fact be too high, as

consumers could be extracting greater value in return for their

data," said a March report commissioned by the British government,

written by Jason Furman, who was President Obama's chief White

House economist. The report also suggests that data-privacy

concerns--a nonmonetary "cost" borne by consumers using digital

platforms--might be better addressed with more competition, if

different companies tried to lure customers by offering tighter

protections.

The huge share of the digital advertising market controlled by

Google and Facebook also means they can charge more for those ads

than they could in a more competitive market--costs that may be

passed on to consumers with higher prices for the goods they buy

online, the reports say. They add that the prominent placement of

ads associated with those platforms also degrades the quality of

the user experience for consumers.

Economists also warn of the potential abuse in the ability of

platforms to control the choices consumers see--and how they see

them--a power that can be used to limit consumer options. That is

the argument behind a private antitrust lawsuit pending against

Apple, accusing it of forcing customers to pay higher prices by

requiring all iPhone software be purchased through its App

Store--where Apple can take a cut--and preventing users from

acquiring the programs directly from developers.

Apple says its App Store isn't a monopoly market and adds that

the controls are imposed to ensure higher quality for its

consumers. The Supreme Court in mid-May rejected Apple's attempt to

dismiss the suit, stating in an opinion that "Apple's theory would

provide a road map for monopolistic retailers to... thwart

effective antitrust enforcement."

The recent spate of research on digital platforms all conclude

those industries naturally tend toward monopoly, for a few reasons.

They cite "network effects," which means that services like social

networks inherently grow more valuable for their customers the more

users they have, a self-reinforcing cycle that tends to foster more

dominance. Those products also work better the more data they can

analyze, compare, and sell--another tendency favoring existing

firms that makes it harder for new competitors to emerge.

The Chicago report says that, with digital platforms, the

"competition in the market" shaping most industries is replaced by

"competition for the market," meaning that once a firm has won the

battle to control a sector, it faces little challenge from other

rivals. The study--led by Yale economist Fiona Scott Morton, an

Obama administration antitrust official--warns of "the difficulty

of entry into digital platform businesses once an incumbent is

established."

The reports all recommend tougher antitrust policies toward the

big digital platforms. That could include more active

investigations of practices used to curb competition, as well as a

more aggressive stance in blocking any future acquisitions by those

firms of potential competitors, like Facebook's purchase of

Instagram and WhatsApp.

But the studies also say there are limits to what antitrust

authorities, like the Justice Department, can do about Google or

the other big tech firms given that technology leads to single-firm

dominance and moves so quickly.

Both the Chicago and U.K. studies conclude that governments will

need new powers to foster more competition.

Write to Jacob M. Schlesinger at jacob.schlesinger@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

June 03, 2019 07:21 ET (11:21 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

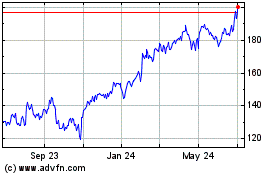

Amazon.com (NASDAQ:AMZN)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

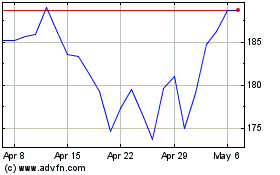

Amazon.com (NASDAQ:AMZN)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024