By Sam Schechner and Parmy Olson

The U.K. government plans to create a regulatory body to force

the removal of harmful content from the internet, one of the most

far-reaching legislative proposals from a host of countries trying

to put a tighter leash on global technology companies.

The U.K. proposal, disclosed in a policy paper published early

Monday, aims to create a new legal obligation for companies

including Facebook Inc. and Alphabet Inc.'s Google to take

"reasonable and proportionate" action on a gamut of illegal or

potentially harmful content published on their platforms, ranging

from terrorist propaganda to cyberbullying and disinformation.

The government said the new regulator would be armed with powers

to enforce compliance, including potentially the power to issue

civil fines for demonstrated failures in some areas.

It said that issue would be refined in coming months through

consultations on an eventual law.

The U.K.'s proposal comes amid renewed momentum from governments

-- from Australia and New Zealand to the European Union -- to force

companies to take more responsibility for the content they

disseminate, from pirated music to extremist manifestos. Those

calls have grown since allegations that Russia abused social-media

tools to inject polarizing disinformation into the 2016 U.S.

presidential election -- and were amplified after last month's

terrorist attack in Christchurch, New Zealand, which the attacker

broadcast live over Facebook.

The new proposals and laws represent a shift from an older

model, where companies have often remained protected by

generation-old rules that shield them from liability for content

their users disseminate. Companies generally have signed on to

voluntary measures to curb the spread of illicit content but

increasingly face legal obligations, too.

Germany, for instance, last year implemented a law that

threatens up to EUR50 million ($56 million) in fines for companies

that systematically fail to remove hate speech.

"The era of self-regulation for online companies is over," said

Jeremy Wright, the U.K.'s digital secretary, in remarks

accompanying the proposal rollout. In an interview with The Wall

Street Journal on Monday, he said he hoped the move would be "a

model that other countries, including the U.S., will want to look

at very carefully."

He said the new regulator could impose sanctions within the

scope of European fines already being levied against companies that

breach the bloc's new privacy rules. Such fines can run into the

billions of dollars, though so far they have been much smaller. Mr.

Wright said the government was also looking at holding individual

company directors liable, as well as the possibility of blocking

internet service providers.

Big tech companies say they already work hard to remove illicit

and harmful content and increasingly use automated

artificial-intelligence tools to do so. While tech executives

increasingly say they also embrace regulation, TechUK, a lobby

group for firms including Facebook, Google, Amazon.com Inc. and

Apple Inc., said that the U.K. proposal would need to become more

specific to avoid subjecting companies to uncertainty. "Not all of

the legitimate concerns about online harms can be addressed through

regulation," the group said.

Facebook said that it supports new internet regulations, and

plans to work with the U.K. government and Parliament to help shape

the rules. But the company also raised what has often been a tense

issue for tech companies facing content restrictions: how to

balance the removal of potentially harmful postings with Silicon

Valley's more general embrace of free speech and enterprise.

"New rules for the internet should protect society from harm

while also supporting innovation, the digital economy and freedom

of speech," said Rebecca Stimson, Facebook's head of U.K. public

policy. "These are complex issues to get right."

Claire Lilley, a public policy manager at Google said the

company looks "forward to looking at the detail of these

suggestions and working in partnership to ensure a free, open and

safer internet."

How to police internet content is one of several topics in a

broader debate over how governments should exercise control over

big technology companies whose products are woven deeply into

millions of businesses and billions of individuals' daily

lives.

In recent months, European nations have pressured the U.S. to

participate in a new round of international talks about how to tax

digital profits. Both the European Union and U.K. have commissioned

reports that suggest potential tweaks to some antitrust enforcement

against big tech firms. The EU also passed a new copyright

directive and a regulation mandating more transparency in how big

tech platforms treat the businesses that rely on them.

On Monday, the EU plans to release a report it commissioned

asking for guidelines for the ethical deployment of

artificial-intelligence tools in the bloc.

Some lobbyists say that adding regulations in Europe or the U.S.

could risk slowing economic growth and putting Western companies at

a disadvantage in a technological race with China. "Tech is

becoming a highly regulated industry, especially in Europe," said

Christian Borggreen, vice president for Europe at U.S.-based

Computer & Communications Industry Association. "It will be

interesting to see how this will impact Europe's ability to create

innovative companies and be a leader for the future."

Removing terrorist content has been a particular focus of many

governments. Last week, security officials from the Group of Seven

nations met with tech companies including Google and Facebook, to

discuss their cooperation with the removal of terrorist content,

and called on the companies to accelerate their work.

The EU is currently debating a proposed law that would threaten

fines of up to 4% of annual world-wide revenue for companies that

don't comply with a regime that mandates the removal of all

terrorist material within an hour of being posted.

For the new U.K. regulator, focusing on the removal of extremist

content could be challenging, however, said Clark Hogan-Taylor, a

manager at counter-extremism software startup Moonshot CVE, which

works with Google. The U.K.'s proposal includes disclosure

requirements for companies, but may prove difficult to police for

accuracy, he said.

"In order for them to fine Facebook for not removing X number of

videos, someone has to know they haven't removed X number of

videos," Mr. Hogan-Taylor said. "How would they measure that?"

Write to Sam Schechner at sam.schechner@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

April 08, 2019 05:44 ET (09:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

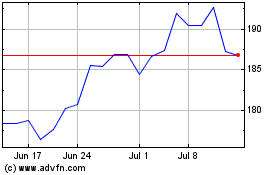

Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOG)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

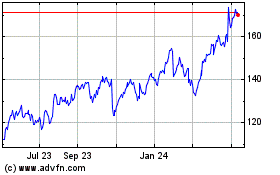

Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOG)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024