By Brent Kendall and Rob Copeland

The Justice Department filed a long-awaited antitrust lawsuit

Tuesday alleging that Google uses anticompetitive tactics to

preserve a monopoly for its flagship search engine and related

advertising business, illegally choking off potential

competition.

The case, filed in a Washington, D.C., federal court, marks the

most aggressive U.S. legal challenge to a company's dominance in

the tech sector in more than two decades, with the potential to

shake up Silicon Valley and beyond. It thrusts Google, once a

startup and now a vast conglomerate, into the type of public

showdown the company has sought to avoid.

The Justice Department alleged that Google, a unit of Alphabet

Inc., is maintaining its status as gatekeeper to the internet

through an unlawful web of exclusionary and interlocking business

agreements that shut out competitors. The government alleged that

Google uses billions of dollars collected from advertisements on

its platform to pay for mobile-phone manufacturers, carriers and

browsers, like Apple Inc.'s Safari, to maintain Google as their

preset, default search engine.

The upshot is that Google has pole position in search on

hundreds of millions of devices in the U.S., with little

opportunity for any other company to make inroads, the government

said.

"Google achieved some success in its early years, and no one

begrudges that," Deputy U.S. Attorney General Jeffrey Rosen said.

"If the government does not enforce its antitrust laws to enable

competition, we could lose the next wave of innovation. If that

happens, Americans may never get to see the next Google."

Google owns or controls search distribution channels accounting

for about 80% of search queries in the U.S., according to the

lawsuit and third-party researchers. The government says that

effectively leaves no room for competition, resulting in less

choice and innovation for consumers, and less competitive prices

for advertisers.

The wide-ranging lawsuit included details on alleged

deliberations within Google aimed at avoiding antitrust scrutiny.

The government quoted Google's chief economist as telling

employees, "We should be careful about what we say in both public

and private."

The lawsuit in particular targeted arrangements under which

Google's search application is preloaded, and can't be deleted, on

mobile phones running its popular Android operating system. Google

has expanded such agreements over the past year since the Justice

Department probe began, the government said

And yet the lawsuit provided little new hard data on such

tie-ups. Alphabet publicly discloses that it pays other companies

to funnel in search traffic; analysts estimate that it pays Apple

alone around $10 billion a year. The lawsuit cited a note from one

senior Apple employee to his Google counterpart: "Our vision is

that we work as if we are one company."

Kent Walker, Google's chief legal officer, said in a statement

that the lawsuit was deeply flawed. "People use Google because they

choose to -- not because they're forced to or because they can't

find alternatives," he said. "Like countless other businesses, we

pay to promote our services, just like a cereal brand might pay a

supermarket to stock its products at the end of a row or on a shelf

at eye level."

Mr. Walker said that, if successful, the lawsuit would result in

higher prices for consumers because Google would have to raise the

cost of its mobile software and hardware.

Alphabet's shares were roughly flat Tuesday, after The Wall

Street Journal first reported news of the impending suit.

The Mountain View, Calif., company, sitting on a $120 billion

cash hoard, is unlikely to shrink from a legal fight. The company

has argued that it faces vigorous competition across its different

operations and that its products and platforms help businesses

small and large reach new customers.

Google's defense against critics of all stripes has long been

rooted in the fact that its services are largely offered to

consumers at little or no cost, undercutting the traditional

antitrust argument centered on potential price harms to those who

use a product.

The lawsuit follows a Justice Department investigation that has

stretched more than a year, and comes amid a broader examination of

the handful of technology companies that play an outsize role in

the U.S. economy and the daily lives of most Americans.

A loss for Google could mean court-ordered changes to how it

operates parts of its business, potentially creating new openings

for rival companies. The Justice Department's lawsuit didn't cite

particular remedies, action that is usually addressed later in a

case. One Justice Department official said nothing is off the

table; the lawsuit said the government would seek structural

changes to Google's business "as needed."

A victory for Google could deal a huge blow to Washington's

overall scrutiny of big tech companies, potentially hobbling other

investigations and enshrining Google's business model after

lawmakers and others challenged its market power. Such an outcome,

however, might spur Congress to take legislative action against the

company.

The case could take years to resolve, and the responsibility for

managing the suit will fall to appointees of the winner of the Nov.

3 presidential election.

The campaign of former Vice President Joe Biden didn't return a

request for comment about how he would approach the lawsuit if

elected. Mr. Biden has called for greater antitrust enforcement

more broadly but has stopped short of saying that big tech

companies should be broken up.

During the Democratic primaries, Mr. Biden said a proposal from

Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren to dismantle Facebook, Google

and Amazon was worth taking "a really hard look at" but said it was

premature to make a final judgment.

The challenge marks a new chapter in the history of Google, a

company formed in a garage in a San Francisco suburb in 1998 -- the

same year Microsoft Corp. was hit with a blockbuster government

antitrust case accusing the software giant of unlawful

monopolization. That case, which eventually resulted in a

settlement, was the last similar government antitrust case against

a major U.S. tech firm.

Google started as a simple search engine with a large and

amorphous mission "to organize the world's information." But over

the past decade or so it has developed into a conglomerate that

does far more than that. Its flagship search engine handles more

than 90% of global search requests, some billions a day, providing

fodder for what has become a vast brokerage of digital advertising.

Its YouTube unit is the world's largest video platform, used by

nearly three-quarters of U.S. adults.

Google has been bruised but never visibly hurt by various

controversies surrounding privacy and allegedly anticompetitive

behavior, and its growth has continued largely unchecked. In 2012,

the last time Google faced close antitrust scrutiny in the U.S.,

the search giant was already one of the largest publicly traded

companies in the nation. Since then, its market value has roughly

tripled to almost $1 trillion.

The company enters this legal showdown under a new generation of

leadership. Co-founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin, both

billionaires, gave up their management roles last year, handing the

reins solely to Sundar Pichai, a soft-spoken, India-born engineer

who earlier in his career helped present Google's antitrust

complaints about Microsoft to regulators.

The chief executive has in his corner Messrs. Page and Brin, who

remain on Alphabet's board and in effective control of the company

thanks to shares that give them, along with former Chief Executive

Eric Schmidt, disproportionate voting power.

Executives inside Google are quick to portray their business

divisions as mere startups in areas -- like hardware, social

networking, cloud computing and health -- where other Silicon

Valley giants are further ahead. Still, that Google has such

breadth points to its omnipresence.

European Union regulators have targeted the company with three

antitrust complaints and fined it about $9 billion. The cases

haven't left a big imprint on Google's businesses there, and

critics say the remedies imposed on it have proved

underwhelming.

In the U.S., nearly all state attorneys general are separately

investigating Google, while three other tech giants -- Facebook

Inc., Apple and Amazon.com Inc. -- likewise face close antitrust

scrutiny. And in Washington, a bipartisan belief is emerging that

the government should do more to police the behavior of top digital

platforms that control widely used tools of communication and

commerce.

A group of 11 state attorneys general, all Republicans, have

joined the Justice Department's case, officials said. More could

join later, according to the court docket. Other states are still

considering their own cases related to Google's search practices,

and a large group of states is considering a case challenging

Google's power in the digital advertising market, The Wall Street

Journal has reported. In the ad-technology market, Google owns

industry-leading tools at every link in the complex chain between

online publishers and advertisers.

The Justice Department also continues to investigate Google's

ad-tech practices.

Democrats on a House antitrust subcommittee released a report

this month following a 16-month inquiry, saying the four tech

giants wield monopoly power and recommending congressional action.

The companies' chief executives testified before the panel in

July.

"It's Google's business model that is the problem," Rep. David

Cicilline (D., R.I.), the subcommittee chairman, told Mr. Pichai.

"Google evolved from a turnstile to the rest of the web to a walled

garden that increasingly keeps users within its sights."

"We see vigorous competition," Mr. Pichai responded, pointing to

travel search sites and product searches on Amazon's online

marketplace. "We are working hard, focused on the users, to

innovate."

Amid the criticism, Google and other tech giants remain broadly

popular and have only gained in might and stature since the start

of the coronavirus pandemic, buoying the U.S. economy -- and stock

market -- during a period of deep uncertainty.

At the same time, Google's growth across a range of business

lines over the years has expanded its pool of critics, with

companies that compete with the search giant, as well as some

Google customers, complaining about its tactics.

Specialized search providers like Yelp Inc. and Tripadvisor Inc.

have long voiced such concerns to U.S. antitrust authorities, and

newer upstarts like search-engine provider DuckDuckGo have spent

time talking to the Justice Department.

News Corp, owner of The Wall Street Journal, has complained to

antitrust authorities at home and abroad about both Google's search

practices and its dominance in digital advertising.

Some Big Tech detractors have called to break up Google and

other dominant companies. Courts have indicated such broad action

should be a last resort and only if the government clears high

legal hurdles, including by showing that lesser remedies are

inadequate.

The outcome could have a considerable impact on the direction of

U.S. antitrust law. The Sherman Act, which prohibits restraints of

trade and attempted monopolization, is broadly worded, leaving

courts wide latitude to interpret its parameters. Because litigated

antitrust cases are rare, any one ruling could affect governing

precedent for future cases.

The tech sector has been a particular challenge for antitrust

enforcers and the courts because the industry evolves so rapidly.

Also, many products and services are offered free to consumers, who

in a sense pay with the valuable personal data companies such as

Google collect.

The search company famously outmaneuvered the Federal Trade

Commission nearly a decade ago.

The FTC, which shares antitrust authority with the Justice

Department, spent more than a year investigating Google but decided

in early 2013 not to bring a case in response to complaints that

the company engaged in "search bias" by favoring its own services

and demoting rivals. Competition staff at the agency deemed the

matter a close call, but said a case challenging Google's search

practices could be tough to win because of what they described as

mixed motives within the company: a desire to both hobble rivals

and advance quality products and services for consumers.

The Justice Department's case doesn't focus on a search-bias

theory.

Google made a handful of voluntary commitments to address other

FTC concerns. The resolution was widely panned by advocates of

stronger antitrust enforcement and continues to be cited as a top

failure. Google's supporters say the FTC's light touch was

appropriate and didn't burden the company as it continued to

grow.

The Justice Department's current antitrust chief, Makan

Delrahim, spent months negotiating with the FTC last year for

jurisdiction to investigate Google this time around. He later

recused himself in the case -- Google was briefly a client years

before while he was in private practice -- as the department's top

brass moved to take charge.

The lawsuit comes after internal tensions, with some department

staffers questioning Attorney General William Barr's push to bring

a case as quickly as possible, the Journal has reported. They

worried the department hadn't yet built an airtight case and feared

a rush to litigation could lead to a loss in court. They also

worried Mr. Barr was driven by an interest in filing a case before

the election. Other staff members were more comfortable moving

ahead.

Mr. Barr has pushed the Justice Department to move ahead on the

belief that antitrust enforcers have been too slow and hesitant to

take action, according to a person familiar with his thinking. He

has taken an unusually hands-on role in several areas of the

department's work and repeatedly voiced interest in investigating

tech-company dominance.

If the Microsoft case from 20 years ago is any guide, Mr. Barr's

concern with speed could run up against the often slow pace of

litigation.

After a circuitous route through the court system, including one

initial trial-court ruling that ordered a breakup, Microsoft

reached a 2002 settlement with the government and changed some

aspects of its commercial behavior but stayed intact. It remained

under court supervision and subject to terms of its consent decree

with the government until 2011.

Antitrust experts have long debated whether the settlement was

tough enough on Microsoft, though most observers believe the

agreement opened up space for a new generation of competitors.

--Ryan Tracy and Sabrina Siddiqui contributed to this

article.

Write to Brent Kendall at brent.kendall@wsj.com and Rob Copeland

at rob.copeland@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

October 20, 2020 14:37 ET (18:37 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

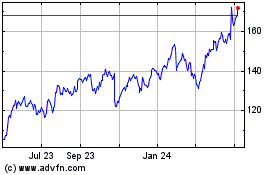

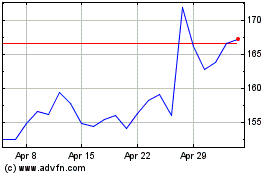

Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOGL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOGL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024