By Dustin Volz and Deepa Seetharaman

U.S. national-security officials traveled to Silicon Valley last

week to forge deeper ties with big tech companies in hopes of

better protecting the 2020 election from foreign intervention. It

didn't go entirely as planned.

At the meeting organized by Facebook Inc. at its headquarters in

Menlo Park, Calif., Shelby Pierson -- named over the summer to lead

the U.S. intelligence community's new election-threats group --

delivered a blunt message to the assembled executives: You need to

share more data with us about your users.

The executives and other U.S. officials in the room were caught

off guard by Ms. Pierson's assertion, according to people in

attendance or briefed on the conversation. After a tense moment,

another official explained that privacy law limited what

social-media platforms could hand over to spy agencies.

A Twitter Inc. executive then offered a rebuke: The Trump

administration was failing to share enough information with tech

firms about election threats, not the other way around, the

executive told the room.

Publicly, the companies in attendance -- Facebook, Alphabet

Inc.'s Google and YouTube, Twitter, and Microsoft Corp. -- said the

daylong meeting was constructive.

But privately, some tech staffers and U.S. officials found the

exchange troubling, people familiar with the meeting said, adding

that it was unusual to see government officials contradict one

another so openly. Some said they worried it could undo some of the

progress made to forge a more unified front against the scourge of

foreign disinformation since, according to the U.S., Russia

unleashed bots and trolls on social media during the 2016

election.

Moscow interfered in "sweeping and systemic fashion" in the 2016

election in an effort to boost then-candidate Donald Trump's

chances, according to the findings of former special counsel Robert

Mueller. Moscow has denied election interference.

In a statement, a senior U.S. intelligence official said the

meeting with Ms. Pierson, who works under the Office of the

Director of National Intelligence, was "collectively viewed as a

positive step" toward continued collaboration.

"The invitation from our industry partners to discuss our shared

commitment to free and fair elections represents an important

signal of forward progress," the official said. "It is vital we

have open and honest conversations about what government and

industry can learn from each other to better understand the tactics

and intentions of our adversaries seeking to undermine our

democratic process, while safeguarding the privacy and civil

liberties of users."

A Twitter spokeswoman declined to comment.

Technology companies and various federal agencies have taken

strides to increase collaboration on addressing foreign

interference since the last presidential election. Those

improvements paid off during the 2018 midterms, when Facebook and

other platforms dismantled small networks of suspected

foreign-backed disinformation accounts based on tips from the

Federal Bureau of Investigation.

But the progress hasn't always been easy. The tech giants remain

wary of appearing too cooperative with security agencies more than

six years after disclosures by former intelligence contractor

Edward Snowden showed how companies supported classified

surveillance programs.

The FBI, Department of Homeland Security and intelligence

agencies, meanwhile, have sought to cajole social-media firms into

more actively policing their networks while sharing more

information about what they find, even as regulatory agencies slap

companies with record-setting billion-dollar fines for privacy

violations. The Federal Trade Commission, the Justice Department

and state law-enforcement officials also have recently launched

various antitrust probes into Facebook and Alphabet.

"I'm going to guess that both sides think the other is still

holding out on them," said Adam Segal, author of a book on the

relationship between Silicon Valley and Washington and the director

of the digital and cyberspace policy program at the Council on

Foreign Relations. "They're both under significant pressure to make

sure [2016] doesn't happen again."

Some people familiar with the exchange last week involving Ms.

Pierson said it reflected a healthy friction between government and

the private sector and that the most important thing is that the

two sides are hashing out issues 14 months before voters go to the

polls. Before 2016, there was virtually no dialogue about foreign

election interference on social media, these people said.

Amid the fallout prompted by 2016, several government agencies

have created new efforts to fight foreign election interference.

FBI Director Christopher Wray created a Foreign Influence Task

Force in 2017 consisting of counterintelligence and cybersecurity

personnel to tackle the threat posed by Russia and other hostile

foreign nations seeking to use social media or other means to

influence U.S. domestic politics or amplify societal divisions. The

National Security Agency and U.S. Cyber Command created a Russia

Small Group, recently made permanent, that launched cyber

operations against the Kremlin-backed Internet Research Agency

during the 2018 midterms.

The companies also have sought to improve their systems for

finding and eliminating disinformation.

Facebook in particular has become better equipped to respond to

disinformation campaigns, said Nathaniel Persily, a Stanford

University professor who studies election integrity. The company

has developed machine-learning algorithms to identify inauthentic

behavior, has placed restrictions on political advertising and has

regularly taken down clusters of accounts that it has associated

with information operations. "The capacity of the tech firms is

dramatically different from what it was in 2016," he said.

Still, barriers remain when it comes to information sharing, Mr.

Persily said. "They can't just turn over all of Facebook's data and

Twitter and Google's data to the government."

April Doss, a former intelligence lawyer at the National

Security Agency, said swapping information about election

disinformation is far more challenging than traditional

partnerships established to share intelligence about more

conventional cyber threats, which raised fewer privacy concerns and

involved more neatly defined adversaries.

"This is such a complicated space," said Ms. Doss, who served as

senior counsel for the Senate Intelligence Committee's Russia

investigation until last year and is now a partner at Saul Ewing

Arnstein & Lehr LLP. "Our traditional models of public-private

interaction really don't have a template for how to handle

this."

Questions have persisted about whether the platforms have done

enough to prepare for 2020, or if the Trump administration has

focused enough on the problem. The Senate Intelligence Committee is

expected to release a report in coming weeks reviewing Russia's

disinformation campaign in 2016 and recommending ways to improve

responses for future elections, according to a congressional

aide.

--Robert McMillan contributed to this article.

Write to Dustin Volz at dustin.volz@wsj.com and Deepa

Seetharaman at Deepa.Seetharaman@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

September 13, 2019 14:50 ET (18:50 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

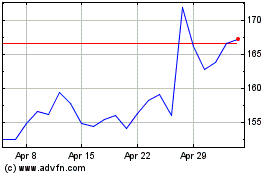

Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOGL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

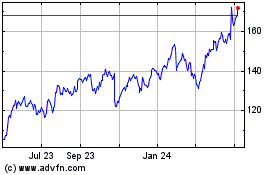

Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOGL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024