By James V. Grimaldi and Brent Kendall

WASHINGTON -- Are big technology companies using monopoly power

to defend and extend their dominance over the U.S. digital

marketplace?

That's the core question antitrust enforcers -- the Justice

Department, the Federal Trade Commission and a number of state

attorneys general -- are asking as they scrutinize four tech giants

for potential violations.

Two separate groups of attorneys general are investigating

Alphabet Inc.'s Google and Facebook Inc. A bipartisan group of 50

attorneys general from U.S. states and territories, led by Texas,

have joined in the Google probe, which was announced Monday.

The Facebook investigation was confirmed Friday by New York

Attorney General Letitia James, who is leading that effort.

Federal antitrust enforcers are also looking at Google and

Facebook, as well as Amazon.com Inc. and Apple Inc.

If a case results from any of those avenues, as many experts

predict, it will take antitrust enforcement into uncharted,

digital-age territory. Courts haven't seen a major monopolization

case since the Justice Department sued Microsoft Corp. two decades

ago.

Federal antitrust laws are broadly written, giving the

government flexibility to apply them to new forms of monopolistic

conduct as the economic landscape evolves. The Sherman Antitrust

Act of 1890, for example, outlaws monopolization and "every

contract, combination, or conspiracy in restraint of trade" that is

considered unreasonable.

Here is a look at arguments that antitrust enforcers could make,

and the companies' potential rejoinders, based on testimony before

Congress and the FTC, interviews with antitrust scholars and people

familiar with the government's preliminary investigations.

The Potential Case Against Google:

--That Google has used its dominance in online search to

solidify its dominance in internet advertising, creating an unfair

advantage over publishers and rival tech firms that sell and place

ads online.

Google, thanks in part to acquisitions of potential rivals such

as DoubleClick, has come to dominate software tools at every layer

between online advertisers and websites, including the main tech

platform that connects buyers and sellers of display ads, this

argument goes.

That middleman status has given it great power, especially

because no one else has anything like the data Google possesses on

publishers, advertisers and what consumers search for.

Advertisers are boosting their spending on digital ads, but much

of the money goes to Google and Facebook, not publishers, whose ad

revenues continue to decline. (News Corp, publisher of The Wall

Street Journal, is among those raising objections.)

--That Google won or maintained its huge market share of online

ad sales by excluding others that could have competed, including

through contractual terms that make it harder for advertisers and

publishers to work with other ad businesses that want to compete

with Google.

Advertisers feel they must use Google's products, rather than

tools from other companies, according to this argument. And in

2016, Google began requiring that advertisers use its tools to buy

ads on its YouTube channel, which has by far the biggest audience

for online videos.

--That Google uses its dominant core businesses to unfairly

favor its other products and services at the expense of rivals.

Google biases its own search results in favor of Google

offerings, the European Union found in levying a $2.7 billion fine

in 2017. One recent study said that less than half of the mobile

and desktop searches on Google result in a user clicking through to

a non-Google site.

The EU also imposed a $5 billion fine on Google for requiring

smartphone makers using Google's market-leading Android operating

system to pre-install Google's search app and its Chrome browser on

their devices.

Google's Defense:

--Google has an enviable place in online advertising, but it

doesn't have monopolistic pricing power.

Google competes with other big tech companies including Facebook

and Amazon for ad dollars, and weak demand for old advertising

models -- not its role in the ad-tech machinery -- is the reason

publishers haven't reaped more of a windfall from digital ads.

--Google's actions are geared toward goals like giving users the

information they want, as quickly as possible. Sometimes that means

directing consumers to Google sites and services, the company

says.

Supreme Court precedent states that companies such as Google

generally have no duty to assist in promoting a rival. In a 2004

ruling, the high court threw out antitrust allegations that Verizon

Communications Inc. provided insufficient service to rival telecom

companies using its phone lines.

--Many of Google's services are free to the public, with

consumers effectively paying with the personal data they

generate.

Judges may face challenges assessing the nontraditional products

that companies like Google and Facebook offer. "It's not like

having 90% of the market for toothpaste," said Cleveland State

University law professor Christopher Sagers.

The Potential Case Against Facebook

--That Facebook has achieved and maintained its dominance

through a pattern of acquiring upstart firms that had become

competitive threats.

Of the roughly 90 companies Facebook bought in 15 years, two

stand out as rivals that could have risen to challenge Facebook:

Instagram, the world's largest photo-sharing service (2012), and

WhatsApp, the largest instant-messaging app (2014).

While antitrust enforcers believe it is illegal for a company to

buy startups for the purpose of killing emerging rivals, neither

the FTC nor Justice Department has brought such a case after the

fact.

--That Facebook acquired monopoly power through deceptive

promises about privacy.

Facing competition from other social-media websites in the early

2000s, Facebook stood out among rivals such as MySpace by promising

consumers superior privacy protections. (From 2005-2011, MySpace

was owned by News Corp, which owns The Wall Street Journal.)

Then, as Facebook became the dominant social-media platform, it

didn't always honor those privacy pledges. The FTC levied a record

$5 billion fine against Facebook this year for privacy

violations.

Under the Sherman Act, it is illegal for a company to acquire

monopoly power by engaging in conduct beyond "competition on the

merits."

--That Facebook abused its market dominance to effectively

require consumers to allow tracking of their internet usage and

exclude competitors in online advertising.

Facebook, the argument goes, can exploit its dominance to

persuade consumers to accept terms allowing the company's use of

their personal data that they would reject if there were a truly

competitive social media platform available.

This allegation led Germany last year to order Facebook to stop

tracking user's web information without consent, though the company

recently won a favorable appellate ruling. The litigation is

ongoing.

--Facebook leverages the power of its data by sharing it with

strategic partners while cutting off access to hobble potential

competitors, such as Twitter Inc.'s Vine, a video app that is now

closed, the claim goes.

Facebook's Defense

--Facebook says it doesn't have monopoly power and faces

numerous rivals, including Twitter, Snapchat, Apple, Pinterest,

Microsoft's Skype, Google and Amazon.

Competition is vigorous because "barriers to entry for digital

platforms are low," said Matt Perault, public policy director of

Facebook, testifying before Congress.

The company also faces growing competition for its members'

time: "Users increasingly spread their time between more and more

services," Mr. Perault said.

--Facebook has acquired companies that have complementary

strengths to make its social-media platform a better experience for

consumers -- and not with the intent of putting a competitor out of

business.

Also, Facebook likely would argue that the companies it bought

wouldn't have grown to the same extent without Facebook's

investment and know-how.

The Potential Case Against Amazon

--That Amazon's rise -- and the tactics that facilitated it --

have squeezed suppliers and harmed rival sellers, creating

different types of disadvantages for consumers, such as lower

product quality and reduced innovation.

Amazon sells not only its own products, but also is a dominant

platform for non-Amazon, third-party sellers. Those vendors now

account for more than half of the company's global sales, and the

platform is crucial to their survival.

Third-party sellers say Amazon imposes fees and terms that the

company couldn't sustain if it faced a real online competitor, and

benefits from an omniscient view of these companies' sales data and

customer relationships.

"It would be as if Walmart owned our malls and Main Streets,

decided which firms could operate in these spaces and on what

terms, and surveilled every move they made," Stacy Mitchell,

co-director of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, an advocacy

group for independent businesses, said in recent congressional

testimony.

A study published by Harvard University found that Amazon used

its data to identify independent sellers' best-selling products and

then introduce its own version. The Amazon brand often then became

the default search option on the platform, the study found.

--That Amazon's tactics can lead to higher prices on other

websites.

Some vendors that could sell their products more cheaply

elsewhere, thanks to fees lower than Amazon's, say they are fearful

of doing so.

"If we sell our products for less on channels outside Amazon and

Amazon detects this, our products will not appear as prominently in

search," toy vendor Molson Hart, who has spoken with the FTC, wrote

in a post on Medium in July.

--That Amazon has limited competition by removing some vendors

from its site.

After Amazon reached a deal to allow Apple to sell iPads,

iPhones and other devices on Amazon, third-party vendors who sold

refurbished Apple products say they were removed.

"I was doing 40 to 50% of business on Amazon," said John

Bumstead, a reseller of refurbished MacBooks who said he was kicked

off Amazon and spoke to the FTC in July. "That chunk of business

evaporates."

Amazon's Defense

--Amazon's growth has been fueled by a determination to offer

consumers low prices and it has competed fairly and legally against

rivals.

The company has invested in supporting third-party sellers and

wants them to succeed. That approach has benefited consumers "in

the form of competitive pricing, great selection and unprecedented

convenience," Amazon associate general counsel Nate Sutton told a

House antitrust subcommittee in July.

Amazon also is far from a retail monopoly, Mr. Sutton said,

because 90% of U.S. retail sales still take place in

bricks-and-mortar stores. Amazon says it doesn't use

seller-specific data in creating its own private-label products,

and offers fewer private-label goods than many of its retail

competitors.

The Potential Case Against Apple

--That Apple has used its platform for iPhone apps to favor its

own products and services over rival offerings.

A Wall Street Journal analysis published in July found that in

the Apple App Store, Apple's own mobile apps routinely appear first

in search results ahead of competitors'.

Music streaming service Spotify has complained to U.S. antitrust

authorities and filed a complaint with the EU's antitrust arm

claiming Apple made it difficult for rival subscription services to

sell to users without using Apple's payment system, which generally

takes a 30% cut of transactions.

--That the company charged inflated prices in its App Store

because iPhone users are prohibited from buying apps elsewhere.

This requirement prompted a private antitrust suit that was

given the green light to proceed by the Supreme Court. Consumers

are stuck with the company's terms because it is expensive to

switch to a rival device, this argument goes.

Apple's Defense

--Apple doesn't have a monopoly in anything -- iPhones have less

than a 50% market share in the U.S.

--Apple says its closed platform protects consumers' data. By

requiring iPhone users to buy exclusively from Apple's store, Apple

ensures the software is safe and won't compromise users' iPhones

with viruses or spyware.

And if Apple favoritism has crippled rivals, then why have

consumers downloaded Spotify 300 million times in the App

Store?

--Apple is under no significant legal requirement to give

competitors a leg up.

"Even if, as Spotify alleges, Apple has monopoly power and has

suppressed competition in its App Store, the government would still

have a difficult time making a case under current doctrine as

interpreted by some courts," said former FTC lawyer Michael Kades,

a director of competition policy at the Washington Center for

Equitable Growth.

Still, Apple has run afoul of antitrust authorities before. In

2012, the Justice Department sued the company for conspiring with

publishers to raise the price of e-books. Courts ruled Apple's

actions were anticompetitive, and the company was ultimately

compelled to pay $450 million.

--Ryan Tracy contributed to this article.

Write to Brent Kendall at brent.kendall@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

September 09, 2019 14:54 ET (18:54 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

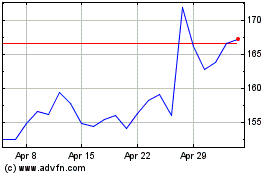

Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOGL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

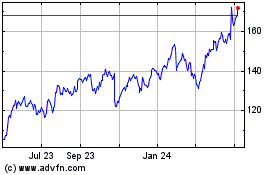

Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOGL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024