By Erich Schwartzel

On the evening of Feb. 4, 2022, an opening ceremony in Beijing

is scheduled to kick off the Winter Olympics, the second time in 14

years the Games will be held in China. But more than medals will be

on the line. The 2022 Games highlight a dilemma facing potential

sponsors: Risk association with an authoritarian regime, or forgo a

much-needed chance at a star turn on the global stage?

Major companies are eager to get in on the action. Visa Inc.,

Coca-Cola Co. and a host of other businesses will be represented in

Beijing as "Olympic Partners," the highest level of sponsorship

available, a tier that covers several Games cycles and is reserved

for those writing the biggest checks and launching the most

aggressive tie-in marketing campaigns. Mars-Wrigley will be there,

too, handing out Snickers, "the official chocolate of the 2022

Winter Olympics and Paralympic Games."

What might have seemed like a no-brainer -- backing a popular

sporting event in a country with 1.4 billion consumers -- may turn

out to be a high-risk gamble. The Olympics could mark the crescendo

of a yearslong trend of some consumers, advocates and Western

lawmakers pointing out what they consider the true costs of working

with a country where horrifying human-rights abuses have been

cataloged by journalists and U.S. officials. At a time when global

companies rely more heavily than ever on the Chinese market, its

government has proven easily triggered by the slightest criticism

-- and unafraid to exact economic punishment on those who cross it

politically.

Already advocates are asking Airbnb Inc., another Olympic

Partner, why its lodging is available in a country where Uighurs in

the province of Xinjiang are housed in concentration camps,

subjected to forced labor and other abuses.

Airbnb is one of many companies that tout themselves as

corporate models of social responsibility, highlighting volunteer

programs and nonprofit outreach in ways that are increasingly a

consideration for consumers deciding how and where to spend their

money. When it comes to China, such activists say, the company

appears to be less concerned.

"Airbnb is very big on social issues, but they are selective on

which social issues," said Zumretay Arkin, the program and advocacy

manager at the World Uyghur Congress, an organization committed to

raising awareness of the minority's plight.

Such criticism presents a Catch-22: It demands an answer from

firms like Airbnb -- but an answer that even alludes to the

existence of Uighur concentration camps could be enough to threaten

its business in China. An Airbnb spokesman declined to comment.

Sports and politics in China have proven a combustible mix in

the past. Just ask the National Basketball Association, still

struggling to regain full access to the market after the Houston

Rockets' general manager tweeted support for pro-independence

activists in Hong Kong in 2019.

In the wake of China's response, prominent players and coaches

withheld criticism and in some cases supported China. Chinese

broadcasts of NBA games were canceled, and sponsorship deals ended

totaling millions of dollars. A state-run network resumed

broadcasting NBA games only last October, a year after the

offending tweet.

In the case of the NBA and other sports, a comment by one person

made an entire organization radioactive, and that could put

Olympic-affiliated companies in a bind. Revenues for Nike Inc., for

instance, grew 24% in China last quarter, compared with 1% in North

America. Behind those sales lies a China-based supply chain

essential to making its entire global operation work.

What, then, might happen to an Olympian's corporate sponsor if

she lands in Beijing and speaks out in support of the Uighurs?

Given China's modus operandi in such matters, shutting up is

likely to be encouraged. Chinese officials reject allegations of

human-rights abuses, and have characterized the camps as vocational

schools. And it's not just the Uighurs to whom advocates will be

drawing attention -- support groups for Tibet and Hong Kong have

also parlayed the Games into an opportunity to raise awareness of

their causes. The Olympic Charter prohibits "demonstration or

political, religious or racial propaganda" at Olympic sites, but in

December the U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Committee said it

wouldn't punish American athletes who protest at the Games.

Some sponsors are hoping the globalized romanticism of the Games

will supersede messy political realities. "We strongly support the

Olympics' vision of building a better world through sport," a

Mars-Wrigley spokeswoman said.

But there are significant unknowns to consider. China's

crackdown on protests in Hong Kong in 2019 caught popular U.S.

businesses in the middle. Protesters targeted Starbucks Corp.

storefronts in Hong Kong, believing the company's local franchisee

supported Beijing. Apple Inc. removed an app used by protesters --

for what the company said were public-safety reasons -- and faced

criticism it was helping the Chinese authorities.

What if similar protests are timed to the 2022 Games? Or if

China, in the 12 months before the Games are to begin, makes an

aggressive move toward Taiwan, a development some believe would

necessitate a U.S. response?

Businesses, meanwhile, are desperate for a ratings bonanza.

Stay-at-home orders have driven more consumers to platforms like

Netflix, which don't carry advertising, making the prospect of a

live broadcast event all the more tantalizing.

There's an appropriate precedent to consider: The case of Mesut

Özil, a midfielder with England's Arsenal soccer club. In late

2019, he posted a comment to his social media accounts decrying the

Uighur internment camps.

Arsenal's next game went off the air in China -- and when

matches resumed, Chinese commentators pretended Özil wasn't on the

field. Özil's avatar disappeared from the Chinese versions of

soccer videogames.

It was professional soccer's China 101 moment. In Hollywood,

several movies that have drawn the ire of Chinese officials taught

everyone to avoid the "three T's": Tibet, Taiwan and Tiananmen

Square.

When choosing Beijing, the International Olympic Committee had

only controversial options. In 2015, when the location of the 2022

Games was being decided, Oslo, Krakow, and Stockholm had dropped

out, leaving just one competitor for Beijing: Almaty,

Kazakhstan.

The IOC opted for "the devil they knew," said Mandie McKeown,

the executive director of the International Tibet Network, who

organized a letter from more than 180 human-rights organizations

calling on governments to boycott the Games.

President Biden has indicated he would not support a boycott

that would stop American athletes from attending. Relocation isn't

in the cards, either.

"We have exhausted that route, so we are going to focus on

corporate sponsors," said Ms. Arkin.

The market forces dependent on the 2022 Games and its host

country at large may prove resilient.

Money talks. Or in this case, keeps silent.

Write to Erich Schwartzel at erich.schwartzel@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

February 12, 2021 11:14 ET (16:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2021 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

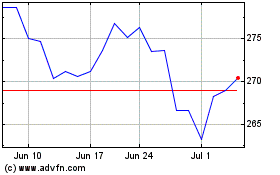

Visa (NYSE:V)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Visa (NYSE:V)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024