By Katherine Blunt and Sarah McFarlane | Photographs by Robert Ormerod for The Wall Street Journal

A decade ago, NextEra, Iberdrola and Enel were sleepy regional

utilities with little name recognition.

Now they are fast-growing giants with market values rivaling the

likes of oil majors Exxon Mobil Corp. and BP PLC, thanks to their

early all-in bets on wind and solar farms.

And still, many people have never heard of them.

Their early lead in the global transition away from oil has put

these companies on track to become the major energy companies of

the coming decades -- the "green energy majors." But they now face

the threat of increased competition as some of the oil titans that

have traditionally dominated the energy industry diversify into

wind and solar power.

If the green majors are nervous about a coming clash, they

aren't showing it. NextEra Energy Inc. Chief Executive James Robo

dismissed the idea that oil majors in the U.S. and Europe posed a

competitive threat at an investor conference this fall, saying that

the companies' green projects were among the worst he had seen.

"I don't worry about the oil majors at all," he told the

audience. "If I have 100 things I worry about at night, it's not

even on the top 100." Mr. Robo declined to be interviewed.

For now, NextEra, Enel SpA and Iberdrola SA are Wall Street

darlings, after Spain's Iberdrola and Italy's Enel became global

builders of green energy projects, while NextEra became America's

largest generator of wind and solar power.

Each of the companies has seen its share price soar in recent

months as investors bet on their ability to lead the transition to

a lower-carbon future with massive investments in renewable energy,

battery storage and improvements to the electric grid.

That transition is expected to accelerate in the U.S. under

President-elect Joe Biden, who has promised to focus on climate

change, and within the European Union and China, where ambitious

carbon-reduction efforts are under way.

Enel and Iberdrola have outlined plans to substantially expand

their portfolios of renewable-energy projects over the next decade

with about $170 billion in collective investments. NextEra, which

hasn't disclosed a long-term spending plan, expects to have

invested $60 billion in renewable energy projects between 2019 and

2022.

Still, analysts caution that increased competition within the

renewables industry could reduce profit margins for the most

established players.

"Oil companies entering the renewables market will need to

accept lower returns on projects initially to gain market share,

and this is going to result in a reduction in margins across the

board," said Fernando Garcia of RBC Capital Markets.

Already, Denmark's Ørsted A/S, a company formerly known as DONG

Energy that focused on oil and gas, has transitioned into a leading

player in offshore wind projects. BP is planning a big shift too:

It says it will increase its clean-energy investments in coming

years as it dramatically scales back oil and gas production.

However, the coronavirus pandemic has decimated demand for

fossil fuels this year, briefly turning U.S. crude prices negative

and forcing the oil industry to lay off thousands of workers and

slash spending. That has sapped the oil giants of much of their

financial strength, making it harder for them to quickly transition

into renewables projects, which require large upfront investment in

order to reap steady returns over a longer period.

While big oil companies once reported double-digit returns on

invested capital -- in the heady days prior to 2014, when crude oil

prices last topped $100 a barrel, some topped 20% annually,

according to FactSet -- the big renewables players have been

winning the race of late with slow and steady single-digit

returns.

"There is no better example than 2020 to show how extremely

different the risk profiles are," said Bernstein analyst Meike

Becker.

Iberdrola, Enel and NextEra have taken different paths to morph

from humdrum utilities into green growth companies.

Originally an Italian utility, Enel was actually later than some

others to home in on wind and solar. Two years after forming its

renewable development arm, Enel Green Power, the company sold about

a third of it in 2010 to pay down corporate debt. Enel then focused

on trying to build nuclear plants in Italy before citizens there

rejected that plan.

But Enel's current chief executive, Francesco Starace, then the

head of that green unit, said he recognized that wind and solar

power had the potential to become competitive in the broader energy

market as costs fell. The unit focused on developing projects in

regions without large subsidies or incentives to show investors

that they could stand on their own.

"At the time, this sounded like blasphemy or idiocy," Mr.

Starace said in an interview. "But we did it stubbornly, and kept

doing it, and eventually this prediction of ours became true."

Mr. Starace became Enel's CEO in 2014, and promptly repurchased

the portion of Enel Green Power that had earlier been sold. He also

reoriented Enel to pursue projects that could be completed within

three years to account for the pace of technological change. That

pretty much eliminated nuclear and coal plants, as well as large

hydroelectric projects, leaving wind and solar farms in the

mix.

Enel is now the world's largest renewable energy producer

outside China, with an EUR84 billion market value, equal to about

$102 billion, and projects in 32 countries. The company has a large

presence in the U.S. and has developed wind and solar farms in

remote areas in countries including Zambia and Chile. The company

plans to spend about EUR70 billion, equivalent to $85 billion, to

nearly triple its generation capacity in the coming decade, which

it expects will give it around 4% of the global market.

Iberdrola, initially a domestic Spanish utility, was an early

pioneer of renewables. It started in 2001, when the company

unveiled a plan to expand internationally and invest in clean

energy sources to help meet growing global demand for power.

It tapped Ignacio Galán to spearhead the strategy as CEO at a

time when wind and solar power were still hugely expensive relative

to other electricity sources. The company had historically focused

on building hydroelectric and nuclear plants, as well as some coal-

and gas-fired ones.

Iberdrola has expanded into renewables in part by aggressively

buying up smaller players with attractive growth prospects. In

October, it agreed to pay $4.3 billion for New Mexico-based

electricity company PNM Resources Inc. -- its eighth deal this

year. It plans to invest heavily in the U.S., where the company is

third in renewables generation capacity behind NextEra and

Berkshire Hathaway Energy, a unit of Warren Buffett's Berkshire

Hathaway Inc.

Mr. Galán said in an interview that Iberdrola at first faced

skepticism about its decision to focus on renewables, but now the

tide has turned: The company's value has multiplied by six on his

watch to around EUR71 billion, or $86 billion, far exceeding his

initial ambition to double its size.

"All we have been fighting for for 20 years, every person

recognizes that was the right decision," he said.

Iberdrola is now the world's second largest renewable energy

generator outside of China, with projects in 30 countries,

including an offshore wind farm in the Baltic Sea and a wind and

solar farm in Australia. It plans to spend EUR75 billion,

equivalent to $91 billion, over the next five years to double its

renewable power capacity.

Florida-based NextEra grew into America's largest renewable

energy producer by keeping debt levels low, capitalizing on federal

tax subsidies available to help finance wind and solar projects

around the country and reinvesting its profits to expand

further.

Over time, it developed the size and scale needed to

consistently underbid other companies in auctions to develop

projects. It operates two Florida utilities and sells renewable

energy output to others. It also operates electric transmission

lines in the U.S. and Canada, as well as natural gas pipelines.

Despite its rapid growth, NextEra has largely flown under the

radar. Some lawmakers in Washington and elsewhere didn't know much

about it until recently. The company several years ago launched a

targeted effort to introduce itself so that its representatives

wouldn't have to start meetings with tedious explanations,

according to a person familiar with the company's strategy.

NextEra declined to comment. The company's executives still

rarely speak to the press.

Investors, however, have been eyeing NextEra for years. Its

share price has roughly tripled over the past five years to reach a

market value of $146 billion, and for the first time it briefly

topped Exxon's value this year in a watershed moment for renewables

producers. Its project backlog totals 15,000 megawatts -- an amount

just larger than its current portfolio, built over two decades.

BP Capital Fund Advisors, a Dallas-based investment adviser that

has historically focused on oil and gas, bought shares in NextEra

in March as part of an effort to diversify with investments in

renewables. The firm was founded by the late T. Boone Pickens, the

oil industry magnate who took an interest in wind and solar power

late in his career. He died last year.

"NextEra stands alone in terms of what it offers in exposure to

the renewable theme," said portfolio manager Ben Cook. "If you're

investing in energy now...that has to be part of the equation."

Write to Katherine Blunt at Katherine.Blunt@wsj.com and Sarah

McFarlane at sarah.mcfarlane@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

December 11, 2020 11:14 ET (16:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

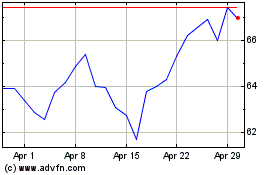

NextEra Energy (NYSE:NEE)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

NextEra Energy (NYSE:NEE)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024