By Melanie Evans and Joseph Walker

Limited stock of the first drug shown to treat Covid-19 is

arriving at hospitals, and location is a driving factor in whether

a patient gets any as states, counties and hospitals use different

approaches to allocate their shares.

Gilead Sciences Inc. is ramping up production of the drug,

remdesivir, which moderately sped recovery for hospitalized

patients in a federal study -- though it isn't known whether the

drug can prevent death from the disease, which is caused by the new

coronavirus. The company is donating early supplies to the federal

government in the U.S., which is allocating it to states.

Food and Drug Administration criteria for remdesivir use under

its May 1 emergency authorization are broad, doctors say, and

little published research points to who might benefit most. States

and counties, which are allocating the drug to hospitals, are

devising widely different methods of awarding the scarce supply.

Hospitals, too, use different methods to decide who to treat. That

means a patient who qualifies in one locale might be shut out in

another.

"We're in a situation of scarcity and we have to find a fair way

to allocate this scarce resource," said Doug White, a doctor and

ethicist at the University of Pittsburgh.

Hospitals affiliated with the University of Pittsburgh decide

who gets the drug by lottery -- though not a totally random one. It

is designed to slightly boost chances of patients from economically

distressed neighborhoods. "Random lotteries will simply propagate

disparities," said Dr. White, who helped develop the system.

It will also increase chances for essential workers, such as bus

drivers, agricultural workers and grocery-store clerks, he

said.

West Virginia hospitals will use the drug for patients first

come, first served. UW Medicine in Seattle is requiring anonymous

patient applications, to avoid possible bias.

Decisions about how best to use remdesivir are the latest

example of the health-care system's need to ration critical goods

and services amid the pandemic. To deal with scarcity, health-care

providers typically rely on plans for how to ethically deploy

resources, where the highest priority isn't the welfare of any one

patient but rather the community, said Robert Truog, director of

the Harvard Medical School Center for Bioethics. But maximizing

benefits can conflict with their fair use, he said.

UPMC, the hospital system and health insurer affiliated with the

University of Pittsburgh, doesn't have enough remdesivir for all

patients who qualify for treatment. "Not by a long shot," Dr. White

said.

States took over allocations to specific hospitals after the

Department of Health and Human Services faced criticism for its

initial distribution. HHS will have shipped 80% of Gilead's initial

donation of about 607,000 doses to states by the end of the week,

the agency said.

An HHS spokeswoman said this week that the government expects to

receive more than 330,000 additional doses from Gilead, but the

company declined to confirm any increased donation. "We are

reviewing the incidence of disease and discussing with the U.S.

government the amount of remdesivir potentially needed through the

end of June," Gilead spokesman Chris Ridley said.

In a National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

study, patients with Covid-19 who were given remdesivir recovered

four days faster than those given a placebo. It is the first drug

to show success in a late-stage clinical trial against the virus,

which has infected more than 1.58 million and killed more than

94,700 in the U.S., data collected by Johns Hopkins University

shows.

That study and another led the FDA to clear the drug for

emergency use for hospitalized patients with low blood-oxygen or

those who either need ventilators to breathe or supplemental oxygen

through a respirator mask or nasal tubes.

That covers virtually all patients admitted to hospitals for

Covid-19, say doctors. Because there isn't enough remdesivir to

treat them all, doctors have called for the National Institutes of

Health, which includes the NIAID, to release detailed study data,

which they say will help to prioritize who should get the drug.

Doctors expect that analyzing granular study data will reveal

patterns showing which variables -- such as symptoms or length of

illness -- predict who will be helped by the drug.

"When you're allocating scarce resources without good

information, it's really dicey," said Rochelle Walensky, chief of

infectious diseases at Massachusetts General Hospital. "We haven't

seen any data; it's been paralyzing."

West Virginia has received approximately 1,160 vials of

remdesivir. It will divide stock equally across four regions of the

state, said Dr. William Ramsey of the West Virginia University

Health Sciences Center, who is chief logistics officer for the

state's pandemic response.

Hospitals in each region will draw from local supply. Patients

qualify for the drug if they meet FDA emergency-use criteria on a

first-come, first-served basis.

California awarded its share by county, based on numbers of

hospitalized Covid-19 patients.

In San Diego County, patients were eligible if they had symptoms

for no more than 10 days or had been on a ventilator for no more

than five, said Ghazala Sharieff, chief medical officer for Scripps

Health. That excluded 18 at Scripps's hospitals who otherwise would

be eligible, Dr. Sharieff said. Doctors identified 14 who met the

county's criteria, while Scripps received doses for five patients,

she said.

The county has changed its formula and will now award doses

based on numbers of each hospitals' Covid-19 patients during the

prior two weeks, Dr. Sharieff said.

A San Diego County spokeswoman said the county switched to

proportional distribution from criteria based on FDA guidance for a

six-dose course of treatment.

Some states have issued guidance that narrowed pools of eligible

patients.

Beaumont Health, which has eight hospitals in Detroit and

Southeast Michigan, received about 400 vials of remdesivir. It

wasn't enough for the roughly 130 Covid-19 patients who met FDA

criteria, said Paul Chittick, section head of infectious disease at

Beaumont Hospital, Royal Oak.

Michigan then issued new guidance calling for hospitals to use

doses for patients with more severe oxygen needs, such as those

with nose tubes or ventilators, Dr. Chittick said. Southfield,

Mich.-based Beaumont has enough drugs for patients who qualify

under the more restrictive criteria, he said.

Michigan's Department of Health and Human Services urged

hospitals to treat severely ill patients and comply with ethical

considerations to treat those who need it most, an agency spokesman

said.

At UW Medicine, doctors fill out an anonymous application for

the drug that includes only medical information needed for criteria

set by the FDA and Washington state to avoid bias, said Shireesha

Dhanireddy, an infectious-disease doctor on the committee that

approves requests.

UW Medicine so far has enough doses, she said, but that may

change with future allotments from the state. "It's not an

unlimited resource," she said.

Write to Melanie Evans at Melanie.Evans@wsj.com and Joseph

Walker at joseph.walker@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

May 22, 2020 10:38 ET (14:38 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

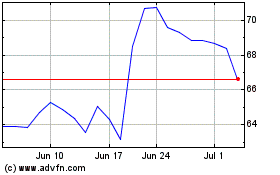

Gilead Sciences (NASDAQ:GILD)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

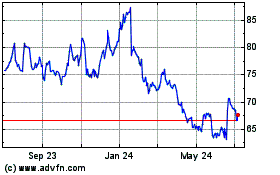

Gilead Sciences (NASDAQ:GILD)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024