By Eliot Brown

This article is being republished as part of our daily

reproduction of WSJ.com articles that also appeared in the U.S.

print edition of The Wall Street Journal (January 25, 2020).

Mattress startup Casper Sleep Inc. typifies the kind of startup

that Silicon Valley investors fawned over through the 2010s,

defined by big vision and rapid growth at the expense of

profits.

Now, it is seeking to go public at the very time that such a

model appears to have fallen out of favor, in a test of what is to

come for dozens of similar loss-heavy startups that need to raise

money as private fundraising becomes more difficult.

The mood in Silicon Valley has changed dramatically in the past

year, as Wall Street investors have proven far less enamored with

many high-profile, high-loss startups than venture capitalists

expected. Uber Technologies Inc.'s stock is down 16% since its

listing last year, and Lyft Inc.'s is down 32%, while the Nasdaq

composite index is up over 18%. Their experience, along with the

failed effort to go public by WeWork parent We Co., have left

startup financiers fearing the same fate for their own investments,

and sparked a scramble across Silicon Valley to stanch the flow of

red ink.

New York-based Casper, which this month filed paperwork for a

planned initial public offering, is considerably smaller than the

ridehailing companies and WeWork. But it shares traits, most

notably a tendency toward burning through capital and a business

model vulnerable to intense competition.

For the first nine months of last year, Casper reported a net

loss of $67 million on $312 million of revenue, with $54 million of

cash. It has raised more than $300 million from investors, with a

valuation on the private markets of $1.1 billion, and sought

additional private funding late last year, according to people

familiar with the matter. That funding was never finalized, and now

it is seeking much-needed cash on the public markets.

The company has for years been marketing itself like a tech

startup, though its IPO prospectus emphasizes other key selling

points, such as the rapid growth of its brand. In six years, it has

become a leading name in mattresses -- aided by $422 million in

marketing in the past four years alone. Its IPO prospectus cited a

survey that 31% of the U.S. is aware of its brand.

Casper says that brand -- and marketing spending -- set it up

well to play into a growing category it calls the "global sleep

economy," which includes everything from pillows to sheets to

sleep-tracking devices. Meanwhile, old incumbent mattress sellers

have struggled with years of slow growth.

The company also is pushing a non-tech approach: expanding its

retail store footprint, which it says is "complementary, not

cannibalistic" to its online sales. It can point to revenue that is

continuing to grow significantly faster than losses -- a trait not

shared by WeWork.

David Hsu, a management professor at the University of

Pennsylvania's Wharton business school, said the company is burning

large sums of money on marketing and could face a tough reception

on Wall Street given the new environment. "There's more discipline

in today's financial markets," Mr. Hsu said.

The effects of that newfound discipline are rippling broadly. A

string of high-profile startups has engaged in cost cutting and

layoffs in the past few weeks, including Oyo Hotels & Homes,

delivery company Rappi Inc. and scooter company Lime Inc. That

follows recent guidance from the largest funder of such companies,

SoftBank Group Corp., that the startups it backs should move toward

profitability -- reversing its prior emphasis on growth.

Fundraising for such startups has become far more difficult.

Companies including Lime and food delivery-focused DoorDash Inc.

-- once able to raise large infusions of cash with little trouble

-- both sought to raise hundreds of millions of dollars in the past

three months and haven't yet succeeded, people familiar with the

attempts said.

Of course, any chill could be fleeting. Money continues to pour

into venture capital funds by the billions, as yield-starved

investors remain anxious of missing the next big thing. Having

soured on consumer tech, venture capitalists say interest has

recently begun to soar in financial-related startups, or

"fintech."

The experience of Casper offers a window into consumer-focused

startups more broadly. Companies including Casper, luggage-maker

Away and sneakers seller Allbirds pioneered a new business model

selling products directly to consumers instead of through other

retailers, often via Google and Facebook ads. Many of them have

tech-like valuations and ambitions to go public. Five-year-old Away

Luggage's $1.4 billion valuation is nearly half the $3.1 billion

market capitalization of luggage leader Samsonite International

S.A.

Casper, which delivers compressed foam beds direct to customers'

doors, launched in 2014 seeking to disrupt the mattress industry by

cutting out middlemen and drawing customers happy to avoid slogging

to mattress stores.

Its early approach -- which is mostly unchanged today -- was

sprinkled with tropes and strategies commonplace among startups

aiming at millennials. It paired clever advertising with a friendly

brand written in sans serif font in a soothing shade of blue.

Celebrity investors like Leonardo DiCaprio were touted. Executives

trumpeted an origin story in which the co-founders realized the

value of sleep after they were overworked in a startup incubator.

Executives less frequently mentioned that co-founder and Chief

Executive Philip Krim previously ran an online mattress company he

eventually sold.

Casper ads flooded podcasts, Instagram and the New York City

subway. The company fashioned itself as "the Nike of sleep," rather

than just a mattress seller, expanding into products like pillows

and dog beds and telling investors it was poised to dominate a

sleeping-related market it estimates at $432 billion. It launched a

magazine devoted to wellness and comfort, with many stories on

sleep.

As sales surged, money rushed in from venture capital investors,

who assigned very high valuations for a mattress company.

Its early success spawned imitators who realized the basic

business model was easy to replicate. Competitors found that Casper

didn't make its own mattresses but procured them from a handful of

U.S. foam factories that supply numerous brands.

Work piled into these factories from dozens of competitors, who

could start companies with little more than a logo and website.

They found the process easy given that some factories design,

produce and ship the mattresses directly to consumers for the

companies. Casper said in its prospectus that one challenge of the

business was its manufacturers share "competitively sensitive

information with our competitors."

But the new entrants in the market -- including Purple

Innovation Inc. and Leesa Sleep LLC -- meant that prices for online

ads targeting mattress-inclined millennials soared ever higher,

dimming the hopes of making a profit.

Purple, a main competitor that went public through a shell

company a couple of years ago, recently turned a profit and sports

a faster growth rate. The stock has almost doubled in the past

year, and its $304 million of revenue in the first nine months of

2019 was just shy of Casper's $312 million.

Sam Bernards, the former CEO of Purple, said he tracked more

than 200 similar companies in the space at the height. While many

were small, they were "all competing for the same keywords on

Google, and the same on Facebook."

The result, he said, was "just economics 101. The more

competition, the higher the spend."

Casper spent $126 million on sales and marketing in 2018, or 36%

of its revenue, down from 42% in 2017.

To find new forms of growth, Casper began opening stores in

malls and hip retail strips, requiring new investment and

employees. Then it started selling through other retailers too,

including U.S. furniture chain Raymour & Flannigan, adding a

middleman and the costs that come with it. Casper said its online

sales have grown faster in cities with retail stores, suggesting

they spur online growth too.

Incumbent online retailers including Amazon.com Inc. and Walmart

Inc. began making their own mattresses, undercutting the others on

price. Casper's lowest-price queen mattress is listed on its

website for $536. An Amazon-branded memory foam queen-sized

mattress sells for $289.

Casper's revenue in the first nine months of 2019 grew 20% from

a year earlier and full-year revenue in 2018 climbed 43%.

"Twenty percent growth isn't that high given the size of the

operating losses," said Jason Stoffer, a partner at venture capital

firm Maveron. He said ideally, a strong direct-to-consumer company

would be closer to profitability at this point.

Write to Eliot Brown at eliot.brown@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

January 25, 2020 02:47 ET (07:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

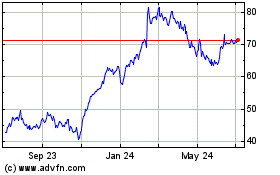

Uber Technologies (NYSE:UBER)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

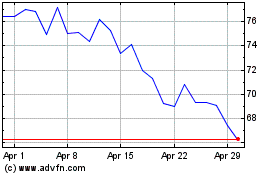

Uber Technologies (NYSE:UBER)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024