Peace Breaks Out Among Activists and Their Prey

November 17 2019 - 11:02AM

Dow Jones News

By Corrie Driebusch

A new playbook is emerging in the world of shareholder activism,

one that calls for quick peace treaties enabling investors and the

companies they target to sidestep costly, protracted battles.

In the past few weeks, AT&T Inc. and Emerson Electric Co.

managed to quickly end high-profile activist challenges -- at least

temporarily -- by agreeing to make modest changes. The hedge funds

besieging them pledged nothing in return.

People involved in the deals insist they are not "settlements,"

the formal arrangements that typically end activist campaigns and

impose strict measures on both parties. Such agreements often

enable activists to name one or more board directors while

preventing them from agitating publicly or waging a proxy fight --

and trading in the stock.

The new setups are more like nonbinding handshake agreements,

and in the case of AT&T and Emerson merely entitle the activist

to recommend or advise on board changes. Emerson has drawn an

investment from D.E. Shaw Group, a hedge-fund firm with an activist

component that praised a new board member the industrial

conglomerate appointed earlier this month.

Elliott Management Corp., AT&T's pursuer, has also reached

non-settlement agreements with Marathon Petroleum Corp. and German

software giant SAP SE in recent months. The hedge-fund firm, one of

the most prolific and aggressive activists, plans to use them as a

template in future campaigns, according to a person familiar with

the matter.

Activists take stakes in companies and push them to make

operational or financial changes to boost their stocks, and have

become a major force shaping the agendas of companies in the U.S.

and Europe.

But both the investors and the companies they target have reason

to cry uncle in the broader war they have been waging the past

several years.

Drawn-out activist campaigns can be expensive and

time-consuming, engendering resentment among executives and board

members. In 2017, Procter & Gamble Co. engaged in a protracted

proxy fight with Trian Fund Management LP. The battle cost at least

$60 million, making it one of the most expensive in history, and

ultimately ended with the consumer-products giant appointing

Trian's Nelson Peltz to its board.

Companies are increasingly attuned to the risk that an activist

will land on their shareholder register, upend their strategy and

undermine their standing with other investors. They frequently

employ so-called defense advisers to game out their response should

they find themselves in an activist's crosshairs, and the

proliferation of informal truces is a sign they are growing more

sophisticated in dealing with the challenge.

Activists, for their part, are grappling with subpar returns and

eager for the increased flexibility and opportunity to tout a quick

victory that the new arrangements afford. An activist hedge fund

index tracked by HFR posted a return of 12% through the end of

October, compared with a return of more than 23% for the S&P

500.

The recent surge in non-settlements fits with a broader

narrative in which Elliott and some of its rivals have worked to

soften their images as they seek to be viewed more as partners than

antagonists.

"There's been a shift toward engagement for some of the larger

activists, " said Lawrence Elbaum, co-head of law firm Vinson &

Elkins LLP's shareholder-activism practice. "These funds want to be

looked at as sophisticated investors that reluctantly turn to the

activism playbook."

The new approach carries risks. A formal settlement is a legal

commitment and without one there is no guarantee one of the parties

won't go back on its promises. Investors with long track records

who are well known to board members, executives and advisers are

more likely to be trusted with a nonbinding agreement than newer,

smaller players, these officials say.

And those changes companies do make may be less consequential

than the ones activists have ushered in over recent years -- to the

benefit of U.S. corporations, many executives acknowledge.

In early September, Elliott sent a pointed 23-page letter to

AT&T, challenging its longtime Chief Executive Randall

Stephenson's acquisition strategy, saying the telecommunications

giant has suffered from "operational and execution issues" over the

past decade and encouraging it to shed assets. It was one of the

biggest activist campaigns in history, given AT&T's market

value of nearly $300 billion.

AT&T reached a resolution with Elliott just seven weeks

later, on the eve of an event to unveil new details of its

much-anticipated HBO Max video-streaming service. The company

promised to "refresh" its board by replacing retiring directors in

the next year and a half. It also outlined a three-year

capital-allocation plan that calls for higher dividends and more

share buybacks, and pledged to actively review its portfolio and

not make any large acquisitions in the near future.

Much of that the Dallas company already planned to do. Elliott

said it approved of the plan and had worked closely with AT&T

to develop it.

Write to Corrie Driebusch at corrie.driebusch@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

November 17, 2019 10:47 ET (15:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

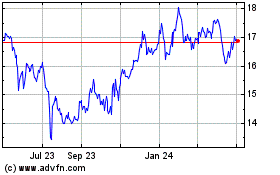

AT&T (NYSE:T)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

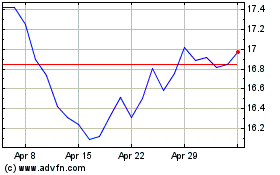

AT&T (NYSE:T)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024