By Andrew Tangel and Andy Pasztor

A senior Boeing Co. pilot raised concerns about a 737 MAX

flight-control system three years ago, but the company didn't alert

federal regulators until 2019, months after two deadly crashes

involving the same system, according to the Federal Aviation

Administration.

In a 2016 instant-message exchange, Mark Forkner, then Boeing's

chief technical pilot for the MAX, and a colleague named Patrik

Gustavsson appeared to discuss the plane maker's modifications of

the system, known as MCAS. The pilots compared notes on problems

they had encountered in 737 MAX flight simulators, according to a

transcript of the messages reviewed by The Wall Street Journal, and

Mr. Forkner described some of the MAX's simulated behavior as

"egregious."

Apparently referring to changes to the system, Mr. Forkner

wrote: "So I basically lied to the regulators (unknowingly)." At

the time, FAA regulators were in the process of certifying the 737

MAX as safe to carry passengers.

Mr. Gustavsson replied: "it wasnt a lie, no one told us that was

the case."

According to a letter FAA head Steve Dickson sent to Boeing on

Friday, the plane maker discovered the messages in February of this

year, several months after a Lion Air 737 MAX crashed in Indonesia

and around a month before another of the jets operated by Ethiopian

Airlines crashed, killing all on board. But Mr. Dickson's letter

said Boeing didn't reveal their existence to the agency until this

week and demanded the plane maker provide an immediate explanation

for the delay.

The messages suggest Boeing's pilots may have encountered some

of the problems that eventually led to the two crashes, which

together claimed 346 lives. MCAS has been implicated in both

crashes.

David Gerger, an attorney for Mr. Forkner, said: "If you read

the whole chat, it is obvious that there was no 'lie' and the

simulator program was not operating properly. Based on what he was

told, Mark thought the plane was safe, and the simulator would be

fixed."

The messages, coupled with questions about why they weren't

shared earlier with the FAA or congressional investigators,

intensify scrutiny on Boeing's management and safety culture.

They also raise the stakes for Boeing at an Oct. 30 hearing of

the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee. Rep. Peter

DeFazio of Oregon, the Democratic chairman of the committee, has

signaled that Boeing Chief Executive Dennis Muilenburg will be

grilled about whether the company misled regulators about MCAS and

then withheld relevant documents from investigators.

Mr. DeFazio said the messages "show deliberate concealment" of a

problematic system that was on the plane but not included in the

training manual. "That's just outrageous." After months assessing

the relative responsibility of federal regulators and the plane

maker in creating the MAX crisis, Mr. DeFazio said now his probe's

focus "is shifting way over to the Boeing side."

"You can't pin this on just this guy," he said, adding that

"this was a cultural problem."

The messages between Messrs. Forkner and Gustavsson highlight

issues relating to Boeing's efforts to get the MAX approved

smoothly -- as well as what pilots were told about MCAS -- both

topics that congressional investigators and federal prosecutors are

focused on, according to people familiar with the probes.

The pilots appeared to discuss Mr. Forkner's role in Boeing's

crafting pilot MAX manuals, which excluded references to MCAS.

After describing the feature "running rampant" in the flight

simulator, Mr. Forkner wrote: "Oh great, that means we have to

update the speed trim description" in those documents. Speed trim

is another flight-control system related to MCAS.

Investigators have been looking into whether such an update

could have alerted FAA officials about the power of MCAS, or

possibly prompted the agency to mandate additional simulator

training for pilots on the new model. Boeing and airlines that

bought the MAX, especially Southwest Airlines Co., were determined

to persuade the FAA that additional simulator training wasn't

required because MCAS was simply an offshoot of the long-standing

speed-trim system previously approved by regulators.

At the end of the exchange, when the aviators complain that

Boeing test pilots failed to alert them about the issues, Mr.

Forkner responded: "They're all so damn busy, and getting pressure

from the program."

Boeing is also the subject of a criminal investigation by the

U.S. Department of Justice, which is working with the Federal

Bureau of Investigation and the Transportation Department's

inspector general's office to delve into how the 737 MAX aircraft

was developed and certified. Last week, the company stripped Mr.

Muilenburg of his dual role as chairman. On Friday, Boeing shed $14

billion in market value, with its shares closing down 6.8% at

$344.

Boeing said Mr. Muilenburg called the FAA chief on Friday to

respond to the concerns raised in his letter, and the company

reiterated it will continue to cooperate with the House panel.

A Boeing spokesman said the company didn't believe it was

appropriate to share the document with the FAA sooner because of

the ongoing criminal investigation. The spokesman said Boeing

shared it with the FAA's parent agency on Thursday because it

planned to turn the letter over to congressional investigators on

Friday.

Separately, the FAA provided Mr. DeFazio's committee with a

batch of emails -- covering the period from 2015 to 2018 -- between

Mr. Forkner and unidentified FAA officials dealing with MAX

issues.

In one dated Jan. 17, 2017, with the name of the agency

recipient blacked out, Mr. Forkner wrote about deleting any mention

of MCAS from certain manuals or computer-based training for pilots.

"We decided we weren't going to cover it," the email said, "since

it's way outside the normal operating envelope" and therefore

pilots wouldn't be expected to experience it.

Ten months earlier, according to another email, Mr. Forkner

raised the same issue, telling another unidentified FAA official

the system was "completely transparent to the flight crew."

Boeing provided the instant messages to the Justice Department

in February after discovering them, and then to the Department of

Transportation's general counsel Thursday night, before giving the

same information to congressional committees investigating the MAX,

according to a person familiar with the matter. The FAA is part of

the Transportation Department. The Justice Department was informed

Boeing would hand over the information to other agencies, this

person added.

"We will continue to follow the direction of the FAA and other

global regulators, as we work to safely return the 737 MAX to

service," Boeing said, adding that the company shared the documents

with the appropriate authorities in a timely manner. A Justice

Department spokesman declined to comment about why the agency

didn't notify aviation regulators about the exchange.

Mr. Forkner served as an important liaison among Boeing, FAA

officials vetting the new model and managers at Southwest, the

MAX's lead customer, which was establishing training programs to

serve as templates for the rest of the industry.

Mr. Forkner left Boeing in 2018 and now works at Southwest. An

attorney for Mr. Gustavsson, who succeeded Mr. Forkner in his old

role and is still at Boeing, couldn't be reached.

A Senate panel is also likely to hold a hearing discussing MAX

later this month. Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D., Conn.), said he

wanted to question Mr. Muilenburg and Boeing's board of directors

about the instant messages, which he said portrayed a "decrepit

culture of corruption in safety."

Write to Andrew Tangel at Andrew.Tangel@wsj.com and Andy Pasztor

at andy.pasztor@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

October 18, 2019 19:45 ET (23:45 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

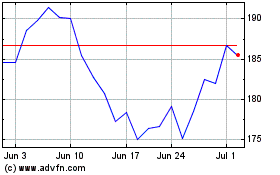

Boeing (NYSE:BA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Boeing (NYSE:BA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024