By Liz Hoffman

Dane Holmes knows a lot of people don't like Wall Street. Not

regulators, not the stock market, not the college graduates

flocking to Silicon Valley. For the past decade, Mr. Holmes has

been the contrarian voice, tasked with presenting a humbler,

friendlier face of Goldman Sachs Group Inc.

He ran investor relations from 2007 to 2017, trying to win back

investors who bolted during the financial crisis. Since then, he

has overseen the bank's human-resources and recruiting efforts,

where he has tried to diversify Goldman's majority male, white

workforce and make finance cool again as a destination for recent

college grads.

At the end of the year, he'll move to San Francisco as chief

executive of Eskalera, a startup that uses data to help companies

find and keep diverse workers. The son of a white mother and black

father, Mr. Holmes joined Chase Manhattan bank through a diversity

recruiting program in 1992 after graduating from Columbia, where he

played basketball and majored in architecture. (He remains a design

geek.)

The Journal talked to Mr. Holmes in his office, where he folded

his 6-foot-8 frame behind a modernist desk that stands out among

Goldman's typically spartan office decor. Here are condensed and

edited excerpts from that conversation:

WSJ: You've had two jobs here, in investor relations and human

resources, where you're selling Goldman to the outside world. That

can't always have been easy.

Mr. Holmes: I always viewed these as two-way jobs, meaning it

was important for me to tell senior management, 'here's what they

think about us, here's where I feel like I have really good

arguments, and here's where I think we could do better.'

When I was in investor relations, the biggest misperception was

that people underestimated how flexible our firm was. They would

say 'if XYZ happens, you're done for.' And I'm like, 'no, if XYZ

happens, we'll make these adjustments.' We have a culture and

business model that allow for it.

On the people side, Goldman Sachs has a reputation of

excellence, but some people think that translates into robotic or

uni-dimensional. They think this is an investment bank and here's

what an investment banker does. Eighty percent of our workforce

doesn't fall into that category. I used to play a recruiting game

with people when I would go to colleges. I would say 'tell me what

your interests are, and I'll tell you what job that is at Goldman

Sachs.' You're into art history? Great. We have people who value

art.

WSJ: But Wall Street isn't drawing young people like it used

to.

Mr. Holmes: Before the crisis, we were growing at 17% a year.

People are obviously attracted to that. As you become a Fortune 100

company, it's hard to keep growing at that pace. Throw in the

financial crisis and the reputational issues that came along with

it, and we had more headwinds.

There's also been this major power shift from employer to

employee. When I was being recruited out of Columbia, I went into a

conference room and somebody told me what it was going to be like

to work there. I had no choice but to accept and frankly, I didn't

have a lot of mechanisms to check it. Today, somebody entering that

room has a great understanding of what their skills are. They've

talked to people who work here. They've been on Glassdoor [a

website where employees leave anonymous reviews of their

employers]. They come in informed. The whole thing has flipped.

WSJ: There's a big debate happening today, particularly in

Silicon Valley, about how much of your personal life you should

bring to the office. What's your view?

Mr. Holmes: We want employees to show up as their authentic

selves. But you're also hired to do a job. So there's a balance

between how much of your personal perspective about what you want

to see happen in the world needs to be executed by your company,

versus wanting to feel safe and comfortable at work and able to

express what matters to you.

WSJ: Speaking of which, millennials take a lot of flak for being

entitled and flighty. Fair or unfair?

Mr. Holmes: This whole positioning of the younger generation --

I hate using millennials as a label -- as 'hoppers' is wrong. The

hopping is more of a byproduct of having a set of things that

they're looking for. If they find it, they'll stay. So the way some

companies respond, figuring they're going to leave in two years no

matter what, I think is a mistake.

WSJ: You're a person of color. So was your predecessor in this

job. Is that a must-have to be a head of HR today? Do you worry

about tokenism?

Mr. Holmes: Tokenism only works when you put somebody in a job

that doesn't matter. It doesn't work for a high-performing company

in a really important job like this one. So, no, I don't worry

about that.

WSJ: Part of your job at Goldman has been to convince people to

work here instead of going to Silicon Valley. Now you're leaving to

go to Silicon Valley. What gives?

Mr. Holmes: I've known Tom Chavez [Eskalera's founder, and the

brother of longtime Goldman executive Martin Chavez] for a couple

of years. He and I spent time talking about our approach to

diversity and how tech can enable that. And he said, 'I would love

you to run this company.' At first I was like, 'haha, yes,

whatever.' But I thought about it. I've got another 10 to 15 years

of real oomph in me and I want to experience something new. And

it's about diversity, which I live and breathe as a person.

WSJ: How can technology help companies be more diverse?

Mr. Holmes: Data is a myth-buster. There was this 'informed

wisdom' at Goldman that said we have fewer women because they leave

for marriage and kids. So we looked at the data we have on certain

women to see whether they're actually staying at home [after they

leave]. But no, they're popping up in other big jobs. Then we

sliced the attrition statistics, and it turns out they aren't

different for women than for men.

So then you ask, OK, why don't we have more women at the top of

the pyramid? We do this thing called lateral recruiting [hiring

senior executives from other banks], which was massively skewing

the talent pool.

WSJ: Men hire other men.

Mr. Holmes: Correct. We were replacing women with men when they

left. So we need to focus on diverse lateral recruiting. You

wouldn't know that without data.

WSJ: How would you grade Wall Street's track record on

diversity?

Mr. Holmes: There's no way to look at it other than

unsatisfactory. And it's really, really unsatisfactory given the

tremendous amount of effort that's been put into it. So we've laid

down the gauntlet. [Earlier this year, Goldman set goals of having

50% of its junior employees in the U.S. be women, 11% black and 14%

Latino.] It doesn't mean we're not going to make mistakes. But the

fact that we've been so public about it is kind of counter to our

culture.

WSJ: Right, you guys usually do things and then brag about them

later.

Mr. Holmes: Correct. Underpromise, overdeliver. But on this one,

we knew that we couldn't facilitate the change we wanted without

it.

WSJ: How do you explain the backlash against technology

companies? Are there lessons in how banks like Goldman dug out from

the crisis?

Mr. Holmes: When you play a significant role in society, like

the financial services industry and the technology industry do, you

should accept a responsibility that reaches the highest standard of

care. One of the problems that Goldman had going into the financial

crisis was that we weren't good communicators. We were very

defensive. And obviously, you've covered us for a long time --

WSJ: I think you want me to say you're excellent now.

Mr. Holmes: [Laughs] I mean, I don't think if you put the

10-year-old version of us with the current version you'd even

recognize it. It's a learning mindset.

WSJ: When I talk to people who leave Goldman after a long time,

some of them say they needed a little deprogramming, like one of

those wildlife reservations where they get rehabilitated before

being released.

Mr. Holmes: This is an intense, driven place and when you're so

maniacally focused on what you're doing, in some ways the world

becomes small. When you leave, suddenly the world seems big and

there are a million things to do. I don't think about it as

deprogramming.

Write to Liz Hoffman at liz.hoffman@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

October 17, 2019 08:14 ET (12:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

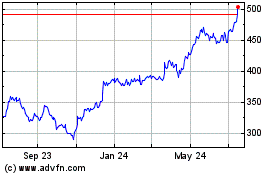

Goldman Sachs (NYSE:GS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

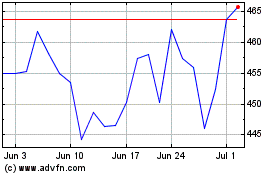

Goldman Sachs (NYSE:GS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024