By Lauren Weber

Drugmakers have hits and misses when it comes to medicines, with

some becoming blockbusters and others producing results so minimal

they barely register in clinical trials.

The same can happen with internal initiatives -- at least

according to Eli Lilly & Co.

A few years ago, the Indianapolis-based pharmaceutical firm

realized that its diversity efforts were yielding little progress

in terms of closing leadership gaps for women and people of color.

The improvements were so meager that Lilly executives estimated it

would take 70 years for the share of women in the company's top

positions to match that of men.

So Lilly, the maker of medicines such as Prozac, Cialis and

Trulicity, decided to try a new approach: It turned to a process

its brand-development teams use to better understand what patients

experience when they are ill, and used that process to get a

clearer picture of the barriers to advancement faced by the women

and people of color it employs.

The "Patient Journey," as Lilly calls the series of surveys,

focus groups and online journaling it asks patients to complete,

became the "Employee Journey." Around 400 women in management

identified as having high potential went through the process, which

began in 2015.

It worked because it took a business process that already had

credibility within the firm and applied it to the often-ambiguous

work of diversity, says Joy Fitzgerald, who became vice president

of diversity and inclusion shortly after the effort began. "That's

like the nirvana of D&I," she says.

The exercise revealed that the opportunities for advancement

Lilly had been presenting to women didn't work for everyone. In

particular, women of color were experiencing some different

challenges than their white counterparts. The feedback that

resulted sparked changes in the company's culture and processes

that have significantly boosted the representation of women and

people of color in Lilly's leadership ranks.

Lack of understanding

From December 2016 to August 2019, the share of women in

management grew to 44% from 38%, and the share of women who report

directly to the CEO rose to 38% from 29%, Lilly says. Women of

color now make up 9% of vice presidents and senior vice presidents

in the U.S., up from 3% in 2016.

The changes Lilly made included altering its recruitment,

development and succession processes based on corporate best

practices, putting measurements in place that are monitored

quarterly and reported to the workforce, and reviewing talent

metrics with all top leaders at least once a year.

Lilly's progress stands out compared with the broader

pharmaceutical and medical-product sector. Women occupy 24% of

senior-vice-president roles and 25% of C-suite jobs in the

industry, according to McKinsey & Co. and LeanIn.Org, which

analyzed data from 21 companies. Women of color account for 4% of

senior V.P.s and 5% of C-suite executives industrywide, while white

men and men of color occupy 63% and 12% of those two positions,

respectively.

Diversity work is "complex, emotional, controversial and tense,"

Ms. Fitzgerald says, adding that "the underpinning of being

vulnerable is that people think you're being a victim, and no one

wants to be a victim, particularly at work."

At Lilly, a Midwestern company founded in 1876 by a Civil War

veteran, politeness is valued, employees say. "we have a very kind

and nice and well-intended culture," says Laurie Kowalevsky, a

marketing executive who spearheaded the journey experiment. "But

there was a lack of understanding about what some of those

experiences were."

The results of the first journey exercise were presented at a

retreat for the executive committee in French Lick, Ind., in

February 2016. Leaders read survey data and anonymized journal

entries and listened to recordings of women describing their

careers at Lilly, including experiences of being overlooked or

having a sense of not belonging.

The stories challenged assumptions held by many at Lilly,

including its chief executive, Dave Ricks.

"I'm married to a working woman, I've got a daughter, I'm the

son of a working woman. I thought the things that happened to women

I loved and knew would not happen in my company," he said in March

of this year, when Lilly was honored with an award for its

diversity work from Catalyst, an organization focused on empowering

women in the workplace. "But they happened."

Looking at data "isn't the same as hearing the voices," adds

Steve Frey, Lilly's head of human resources and diversity. The

company shared the results with the entire workforce.

The results also led to a troubling realization by the team that

had organized the process. By focusing on women in fairly senior

roles, it had failed to get a critical mass of voices of women of

color, leading to an incomplete picture of women's experiences at

Lilly.

"The gap was pointing to the problem," says Ms. Kowalevsky. "The

representation of African-American women in the pipeline wasn't

where you would want it to be."

Standing ovation

Shortly after, Lilly went through the employee journey process

with African-American, Asian and Latino employees specifically. As

in the first exercise, employees were asked to participate in focus

groups and take extensive surveys.

Among them was Shannon Alston Rush, currently head of Lilly's

diabetes business in the U.K., Ireland and the Nordic countries.

Ms. Rush now chairs Lilly's women's resource group, called Women's

Initiative for Leading at Lilly, which has around 2,000 members.

When Ms. Rush became the group's leader, she introduced herself by

describing many of her experiences at the company at a meeting

attended by more than 1,000 employees.

"It took me weeks to unravel my 20 years here," she says. During

her 40-minute presentation, Ms. Rush talked about how it felt to be

the only African-American woman in a room at many times during her

career, "to be in the room where you're leading the

[profit-and-loss statement] yet no one is asking you the

questions." Afterward, she received a standing ovation.

Mr. Ricks has conducted two leadership programs, called Emerge,

for senior managers. The first engaged about 15 African-American

women; the second was for 28 Latino and Asian women. The programs

were a combination of relationship-building and leadership

development, with Mr. Ricks teaching case studies based on

decisions he has faced in his career.

"It was important to be recognized like that, without asking,

'How do I get on that list?' " says Ms. Rush, who participated in

the first session. "It meant a lot that our CEO took three days off

his calendar" for the program.

Some problems can be addressed by "waving your CEO wand," giving

orders and getting results, Mr. Ricks said at the Catalyst

ceremony. Other problems, he said, can't be fixed that way. For

those, "you have to make things important, and one of the primary

ways leaders can do that, especially the CEO, is by paying

attention to them."

Ms. Fitzgerald believes that commitment is filtering through the

organization, sometimes in unexpected ways. Every year, Lilly hosts

an African-American forum focused on career development and other

issues. In prior years, the event mostly drew African-American

employees. When registration opened this year, the 1,200 available

spots plus the wait list filled up within two hours, and the

majority of participants were Caucasian, she says, suggesting that

interest is broader and stronger than before.

Lilly employees also have begun to share a vocabulary that helps

them have conversations about what might once have been awkward

topics, executives say. "I've been in the room where a man said to

someone, 'Did you just mansplain that to her?' " says Ms.

Kowalevsky. "People now feel more comfortable than not saying those

things."

The company is looking ahead, resetting goals, and already has

begun a journey process for LGBTQ employees. "We've made a lot of

progress in the last five years or so," says Mr. Frey. "We're not

where we want to be still."

Ms. Weber is a Wall Street Journal reporter in New York. Email

her at lauren.weber@wsj.com.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

October 15, 2019 00:17 ET (04:17 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

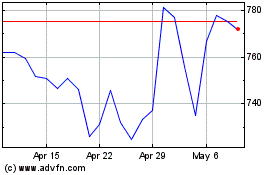

Eli Lilly (NYSE:LLY)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Eli Lilly (NYSE:LLY)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024