By Sarah E. Needleman

This article is being republished as part of our daily

reproduction of WSJ.com articles that also appeared in the U.S.

print edition of The Wall Street Journal (June 18, 2019).

Amazon.com Inc.'s yearslong effort to invade the $130 billion

videogame industry is hitting a rough patch.

The company last week laid off several dozen employees from its

division that develops videogames, according to people familiar

with the matter. The layoffs come as Amazon has struggled to

produce a hit and make inroads with internal software it hoped

would lead more game developers into becoming customers of its

cloud service, Amazon Web Services.

An Amazon spokesman declined to specify exactly how many jobs it

eliminated. In a statement, the company said it is reorganizing to

focus on two games under development and new projects, and would

assist the affected employees in finding jobs within Amazon.

Videogames publication Kotaku earlier reported on the layoffs.

Amazon's troubles in videogame creation show how even one of the

world's biggest companies can struggle to break into different

markets. The online retail giant causes concern among companies in

other industries when it moves into their businesses. Amazon has

become a leader in cloud computing, a major Hollywood studio and is

emerging as a threat in advertising, logistics and health care.

It has had its missteps, too. Earlier in the week, Amazon said

it would shut down its restaurant delivery service after it failed

to gain traction. Its attempt at selling its own smartphone failed

several years ago.

Amazon's overall push into videogames isn't a bust. The company

in 2014 purchased for $980 million Twitch Interactive Inc., a

live-streaming platform beloved by gamers. Last year, people spent

505 billion hours watching live-streams on Twitch, up from 355

billion in 2017, according to its own data. Wedbush analyst Michael

Pachter estimates Twitch made $400 million in revenue last year,

double from the year Amazon purchased it.

Amazon's videogame woes have mostly stemmed from its Amazon Game

Studios unit, which the company formed in 2012 and today has

roughly 800 employees across three studios in Seattle, San Diego

and Irvine, Calif.

Amazon Game Studios initially focused on publishing other

developers' mobile games, but in 2015 it switched to developing its

own titles for personal computers. The unit announced in 2016 that

it had three significant PC games under way. Since then, one has

been canceled, while the other two remain under development.

"In spite of our efforts, we didn't achieve the breakthrough

that made the game what we all hoped it could be," Amazon staff

wrote in a Reddit post last year revealing the cancellation of

"Breakaway," one of the three PC games it announced. The company

had described it as an online multiplayer "mythological sports

brawler."

One additional PC game was never announced publicly but has been

canceled, according to people familiar with the matter. Amazon Game

Studios last year released a car-racing title called "Grand Tour

Game" for consoles, but it has sold poorly.

To aid its efforts, Amazon recruited several industry

heavyweights over the years, including former Sony Corp. executive

John Smedley and game designers Kim Swift and Clint Hocking. Mr.

Smedley still works for the company, but Ms. Swift and Mr. Hocking

left years ago.

Like Hollywood movies, videogames can take years to make, and it

isn't unusual for some to get scrubbed upon receiving harsh

feedback from testers. The game-creation business is so competitive

that success in it can be elusive even for a cash-rich company like

Amazon.

The usual game-industry headwinds aren't entirely to blame for

Amazon's challenges, according to current and former employees.

Amazon sought to build powerful games off software it acquired in

2016, with the goal of enticing more game makers to use its cloud

servers to host their wares online.

The software, a so-called engine known as Lumberyard, wasn't

built for the kind of multiplayer games Amazon wanted to make, and

the company's efforts to retool it have proved difficult, the

current and former employees said. As a result, making "Breakaway,"

for example, was like driving a train while the tracks were still

being laid down, these people explained.

"They're still ironing out the kinks of what it means to own and

maintain your own engine," said a developer working at Amazon Game

Studios, referring to a separate team responsible for

Lumberyard.

Game engines represent a little known but critically important

part of the industry. While major publishers such as Electronic

Arts Inc. have proprietary game-creation software, scores of

developers rely on commercial engines from companies such as

"Fortnite" maker Epic Games Inc. and Unity Technologies Inc.

Amazon's Lumberyard, which is free for developers, has yet to

reel in a true blockbuster.

Amazon may soon allow its game studios to use other company's

engines, according to people familiar with the matter. That could

potentially propel the development of its games, but also require

Amazon to pay a subscription fee or royalty on sales.

Other tech giants are attempting to break into game development.

Google said in March that it was building a game studio to be led

by Jade Raymond, known for her work on Ubisoft Entertainment SA's

"Assassin's Creed" franchise. The Alphabet Inc. unit also is

planning to launch a Netflix-like streaming service for videogames

called Stadia in November, a move that some analysts expect Amazon

to jump into as well.

--Dana Mattioli contributed to this article.

Write to Sarah E. Needleman at sarah.needleman@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

June 18, 2019 02:47 ET (06:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

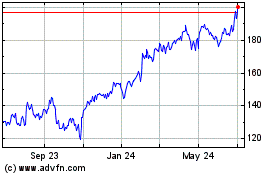

Amazon.com (NASDAQ:AMZN)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

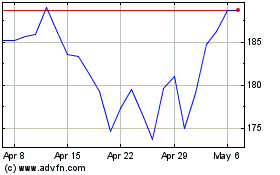

Amazon.com (NASDAQ:AMZN)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024