By Suzanne McGee

This article is being republished as part of our daily

reproduction of WSJ.com articles that also appeared in the U.S.

print edition of The Wall Street Journal (May 6, 2019).

Marianne Swenson, a Boston-based labor lawyer, had done her

research; she knew that the less she paid in fees for the mutual

funds in her 401(k) portfolio, the more money she'd have to grow in

her nest egg over the years. And she knew that there were plenty of

S&P 500 index funds -- a key ingredient in the portfolios of

many fee-conscious investors -- charging less than 0.10% a

year.

Why then, Ms. Swenson wondered, was she paying 0.61% of assets

annually for her S&P 500 index fund, the only one offered by

her 401(k) plan?

"I am shocked, especially so when many other funds offer similar

funds charging a mere fraction" of what she pays, Ms. Swenson says.

"I know how the cost savings, and the costs, can accumulate over

time."

Even as providers like Fidelity Investments, BlackRock and

Vanguard Group roll out zero-fee mutual funds and exchange-traded

funds, it remains easy for investors to find themselves trapped

into paying relatively high fees and unable -- like Ms. Swenson --

to rationalize them.

Index-fee gap

The most striking example is the enduring gap in fees for

ordinary index funds, which cost relatively little to oversee and

are designed to replicate the performance of a specific index.

True, both research firm Morningstar Inc. and the Investment

Company Institute (the fund industry's professional association)

note that investors overall are paying lower fees these days;

Morningstar pegged the 2018 savings alone at $5.5 billion. But the

range in index-fund fees remains wide.

For mutual funds that track the S&P 500, investors can pay

as little as 0.03% for Schwab S&P 500 Index Fund (SWPPX) -- or

as much as 2.33% for the Class C shares of Rydex S&P 500 Fund

(RYSYX), a fee level that might make even the lauded manager of an

actively managed emerging-markets fund blush. In the middle are

offerings like Principal Financial Group's Principal LargeCap

S&P 500 Index Fund Class C shares (PLICX), which have a net

expense ratio of 1.3%. Ms. Swenson's S&P 500 index fund is

provided by State Street, which joins many other providers in

having an expense ratio just below or just above 0.5%. (Rydex's

parent, Guggenheim Partners, as well as State Street didn't respond

to requests for comment.)

Advisers and others point out that investors often get some

benefits in exchange for higher fees. For instance, if your share

class is pricier because you buy it through a brokerage firm or

it's part of your 401(k), you may be paying (indirectly) for

asset-allocation advice, as well as online access to your account

and a variety of record-keeping services. Perhaps your employer

matches some portion of your 401(k) contributions. Would you swap

that match for a less pricey fund?

But fee differences show up in returns. Fidelity 500 Index Fund

(FXAIX), with a 0.02% net expense ratio, generated a total return

of 13.48% in the 12 months through April and had a three-year

return of 14.86%, according to Morningstar. The Principal Group's

fund produced total returns of 12.02% and 13.36%, respectively. And

that Rydex fund? Its total returns were 10.65% and 12.10%.

Getting 'tricky very quickly'

Low-cost funds have attracted huge inflows of money from

investors. Some assets, however, remain stuck in higher-cost funds.

The number of share classes in the lowest-cost index funds nearly

tripled over the past decade to 164 at the end of April, while

assets soared to $2.23 trillion from $210.34 billion in 2009,

according to data from Broadridge Financial Solutions. But there is

still more than $121.16 billion invested in index funds levying

fees north of 0.5%.

Part of the explanation for the amount in higher-cost funds is

that those funds often form part of 401(k) plans, and the companies

that offer those plans to employees simply don't have the clout to

insist on access to the cheapest offerings. Another problem for

employees at many companies is that, in addition to the funds'

fees, they are paying fees to cover record-keeping and other

back-office costs that otherwise would fall on the shoulders of

their employer.

"On some level, you are subsidizing the costs of your 401(k)

plan," says Andrew Houte, director of retirement planning at Next

Level Planning & Wealth Management in Brookfield, Wis. Clients

of his who might work for large companies in the region will pay

less in mutual-fund fees than will those who work for a small local

business with only a few dozen participants in a 401(k) plan. "It

can get tough for these smaller employers to offer a plan, and

offer a match, and still pay for record-keeping and other

paperwork," he says. So they simply pass those costs along to

employees.

"This can get tricky very quickly," says Charles Sachs,

Miami-based director of planning at the wealth advisory division of

Kaufman Rossin. "If we find an ATM fee or an overdraft fee on our

bank statements, we see it and understand it. But the amount of

mutual-fund fees aren't explicitly deducted from returns on any

statement, so the true impact of those fees becomes more opaque and

harder to understand.

Other gaps

Wide discrepancies in fees aren't unique to Index funds; they

can be found in actively managed funds as well.

Washington Mutual Investors Fund, offered by Capital Group's

American Funds, is a case in point. It has no fewer than 17

different share classes, with annual operating expenses that range

from 0.29% (if you are part of a large 401(k) plan) to 1.42% (if

you're investing in the fund for your "529" education-savings

plan). Everything north of 0.23% in management fees represents some

kind of distribution fee, commission or service fee, according to

the fund's prospectus -- something that investors are paying for

over and above the cost of simply generating the fund's investment

returns.

Craig Duglin, senior product manager at Los Angeles-based

Capital Group, says his funds offer some of the lowest management

fees in the industry. As for the range in fees, meaning that there

can be a big difference between the management fee and the total

cost, investors "have to assess the value; what the outcome is for

the fee," he says. Part of that is performance, says Jacob Gerber,

investment director for Washington Mutual Investors Fund. "We

produce results over time that have outpaced the broad market, and

do it with lower volatility."

Meanwhile, as target-date funds become a default investment of

choice for retirement-plan sponsors, advisers are stumbling across

pricing discrepancies in this area as well.

Linda Rogers, Memphis-based founder of Planning Within Reach, a

financial advisory firm, found that Fidelity offered three

different options for a client planning to retire in 2045 -- each

with a different fee. This was irksome to her and her client, but

Fidelity explains the divergence this way: "The pricing differences

for our three strategies (Freedom, Freedom Balanced and Freedom

Index) reflect the different index allocations and investment

flexibility" in each, says Adam Banker, a spokesman for the firm.

The least expensive option employs only low-cost index

strategies.

What investors can do

Investors don't have to simply shut up and pay up if they're

annoyed by higher fees for funds in a 401(k) account while

enviously eyeing those lucky enough to have access to lower-cost

alternatives. The first step is to raise your concerns with your

company's human-resources division and ask them to review the array

of investment options. "I have found that many companies are

willing to explore this, if they can make the case that they're

improving the plan for employees," says Eric Walters, president of

Silvercrest Wealth Planning in Denver.

Also, you're not locked into investing in 401(k)-eligible plans

to save for retirement -- you can also invest in an individual

retirement account. If you find you can access a particular mutual

fund at a lower cost via your IRA, you can do so, and keep your

401(k) assets invested in other funds where fees aren't as high.

Rolling over your 401(k) into an IRA when you leave a job also will

give you more investment flexibility, especially if you have a

sizable balance.

And finally, higher-net-worth investors working for larger

employers may find that their 401(k) plans offer a "brokerage

window": Rather than investing in whatever funds are made available

to you by your employer, you can create a brokerage account under

the umbrella of your 401(k) and invest in whatever you wish.

Ms. McGee is a writer in New England. She can be reached at

reports@wsj.com.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

May 06, 2019 02:47 ET (06:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

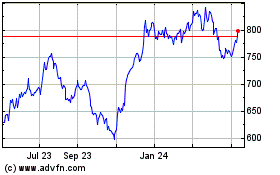

BlackRock (NYSE:BLK)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

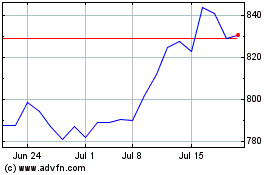

BlackRock (NYSE:BLK)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024