Kroger adjusts operations and invests in technology to hang on

to customers who avoid stores; 'we've got to get our butts in

gear'

By Heather Haddon

This article is being republished as part of our daily

reproduction of WSJ.com articles that also appeared in the U.S.

print edition of The Wall Street Journal (April 22, 2019).

Nobody can say Rodney McMullen doesn't know the grocery

business. He started as a bagger at Kroger Co. when he was in

college, rising through the ranks to become chief financial

officer, then chief executive officer, of America's biggest

supermarket chain.

But can he lead the 2,764-store Cincinnati-based company through

the changes upending the supermarket industry?

"You are in Cincinnati. You are a conservative bunch of people,"

said Bill Smead, chief executive of Smead Capital Management and a

Kroger investor. "Does anyone's blood pulse through their veins

with an entrepreneurial bent?"

Not since Walmart Inc. first pushed into groceries in the late

1980s have traditional chains faced so many challenges. E-commerce

is transforming the business, forcing cash-strapped companies to

overhaul their operations and invest heavily in technology and

talent to keep customers from straying to Amazon.com Inc. At the

same time, they have to keep food prices as low as consumers have

come to expect.

The transition has proven rough for Kroger, which stayed focused

on store sales long after mass-merchant competitors were investing

in online-ordering technology and delivery services. Executives

have debated which investments to make and how drastically to

change the company's business model. Some would-be technology

partners have been turned off by what they see as the grocer's

conservative culture -- including members of one group who stormed

out of a meeting in protest.

Mr. McMullen knows it is a pivotal moment for the company and

that investors are concerned. "We've got to get our butts in gear,"

he said in an interview. "There was no doubt we were behind." He

said he believes Kroger executives have devised a plan to help it

grow again.

Few American retailers have managed the online transition

smoothly. Target Corp. and Walmart struggled before improving

stores and e-commerce operations. Sears Holdings Corp. filed for

bankruptcy protection in October. Toys "R" Us was liquidated in

March 2018.

Online ordering and delivery has been around in the U.S. grocery

business for decades, but it hasn't caught on as rapidly as it has

in other sectors. Many U.S. shoppers live close to supermarkets and

prefer to select food from the aisles. That is changing as more

young people form families and older people get more comfortable

ordering online. One option proving especially popular is for

consumers to order groceries online for pickup in a store's parking

lot.

Online purchases account for just 5% of the roughly $1 trillion

U.S. food and consumer-product market, according to Nielsen. Yet

online sales are growing 40% annually, while in-store sales have

been flat for years.

"It's like driving on the autobahn," Mr. McMullen told investors

last fall. "It's incredibly exciting. But there's a lot going on,

and it's going on fast."

Years ago Walmart became the largest food seller in the U.S.,

while Kroger remains the biggest supermarket chain by stores and

sales. Walmart boosted its delivery business with its 2016 purchase

of Jet.com, bringing on Jet executives to accelerate online grocery

sales. Target bought Shipt Inc., another grocery delivery service,

in 2017. And Amazon broadened its reach into the grocery business

by buying Whole Foods in 2017, although it, too, has struggled with

online delivery of groceries.

To catch up, Kroger has budgeted $4 billion for investments,

including warehouses managed by robots, a meal-kit company and

digitally enabled shelves that market products to customers through

LED displays. Last year, it formed a partnership with an

autonomous-vehicle startup, Nuro Inc., and started selling its line

of natural and organic products on Alibaba Group Holding Ltd.'s

Tmall site in China.

Those investments are denting its profits at a time of intense

competition to sell groceries cheaply. Its shares are down 17%

since June 2017, when Amazon said it would buy Whole Foods, and

have dropped after five of Kroger's eight latest quarterly earnings

reports.

Sapphire Star Capital, an investment fund, sold a $350,000 stake

in Kroger in September. "We just had to cut them loose," said

Michael Borgen, the fund's chief executive. "They just got too

volatile."

John San Marco, a research analyst at Neuberger Berman, an

investment-management firm that owns Kroger stock, said the company

is doing the right thing by investing in online operations, even if

it dents profitability in the near term. "Kroger is in the very

early innings of a business transformation," he said. "This isn't a

one and done."

Mr. McMullen, who became CEO in 2014, has acknowledged that

Kroger was slow to invest online. He said many competitors also

avoided investing in online operations until recently. On Kroger's

latest earnings call in March, he sought to reassure investors that

Kroger's investments will pay off. "You have to start somewhere,

and you have to learn," he said.

Kroger has a record of dabbling in digital projects without

committing to more significant changes to its business, current and

former employees say.

In 2000, when Mr. McMullen was CFO, Kroger canceled a pilot

delivery program in Columbus, Ohio, because of low demand. Another

pilot has been running at Kroger's King Soopers chain in Denver for

two decades without expanding to additional parts of the

country.

Another such effort began about seven years ago when executives

were told that Amazon had surpassed Kroger as a top seller of

Procter & Gamble Co.'s diapers.

At the time, Kroger's digital-operations staff fit into a small

room at its Cincinnati headquarters. They started meeting every

Friday at 7 a.m. to discuss ways to improve Kroger's digital

efforts. The operation soon expanded.

Kroger didn't have the infrastructure to ship goods to

customers. Building warehouses and wooing tech talent to build an

online-grocery portal would have cost hundreds of millions of

dollars, employees say.

Kroger managers remained focused on their stores, where sales

determine their compensation and chances for advancement. Some

believed boosting online sales would create extra work and distract

the company from maximizing store revenues, former executives

said.

"Most of us, when we say the digital world, automatically

conclude that e-commerce is where everything is going," then-CEO

David Dillon told investors in 2013. "I don't draw that same

conclusion." Reaching customers digitally also included things like

online coupons and social media, he said.

Amazon continued to siphon diaper sales from Kroger and other

retailers, notching roughly $500 million in diaper sales last year,

according to estimates by market research firm Edge by

Ascential.

Kroger turned to acquisitions to boost its digital reach. It

bought Vitacost.com, an online retailer of natural foods and

supplements, for $280 million in 2014. But Kroger was slow to

integrate Vitacost's technology into its operations. That

frustrated Vitacost's founders and Kroger employees who had

brokered the deal, according to people from both companies.

A meeting at Vitacost's Boca Raton, Fla., headquarters soon

after the deal closed underscored the divide. Vitacost employees

suggested emailing promotions to customers so that discounts could

be tweaked more often than through the paper circulars that Kroger

planned months in advance.

Kroger executives balked, with one marketing head saying that

Vitacost was a rounding error in the company's overall balance

sheet and it wouldn't just change its promotional plans, according

to people from both companies. Some Vitacost executives walked out

in protest.

Kroger was slow to add a link to Vitacost on its website or

place signs in its stores promoting Vitacost. Officials from the

two operations clashed over whether to let Vitacost accept Apple

Pay or PayPal, the people said. Vitacost's revenue grew less than

that company had expected. Engineers and executives left the

company. Other Vitacost executives have remained at Kroger and

helped on various technology initiatives.

Some at Kroger acknowledge more could have been done to make its

Vitacost investment pay off. "Some look at us and argue we haven't

done much with Vitacost," said Michael Schlotman, who stepped down

as chief financial officer this month and will retire at the end of

the year. "It's a fair assessment."

Kroger now accepts PayPal on Vitacost but not its other

e-commerce sites. It uses Vitacost's technology for a ship-to-home

grocery service that made its debut last year. Executives hope the

service will win back business from Amazon's subscription service

for staple goods.

"It's just starting to get legs," Mr. McMullen said.

Kroger recently tried to partner with, invest in or acquire

three different startups: Shipt, the online grocery delivery

service; meal-kit company Plated; and Boxed.com, a bulk online

retailer, according to people familiar with those efforts. None

panned out.

Target bought Shipt in December 2017. National grocery chain

Albertsons Cos. purchased Plated in 2017 for more than Kroger

offered, according to people familiar with the negotiations. Boxed

executives and investors balked over terms offered by Kroger in

negotiations, talks stalled and Kroger never made a formal

offer.

"They aren't willing to pay enough to buy technical talent,"

said one person involved in negotiations between Kroger and those

startups.

Yael Cosset, Kroger's chief digital officer, declined to comment

on any negotiations. He said the company tends to be more

conservative in rolling out tech pilots that directly affect

customers in stores, but has moved faster behind the scenes on

other efforts.

Kroger officials say the company is now working with Microsoft

Corp., Oracle Corp., IBM Corp. and other tech companies, and is

spreading the word about Kroger to potential tech startup partners

at the Cincinnati-based Cintrifuse startup investment fund.

"Kroger has been very bold in their vision," said Luke Jensen,

chief executive of Ocado Solutions, a division of U.K.-based

automated-grocery company Ocado Group PLC that Kroger has invested

in to build a network of automated warehouses for online retail in

the U.S. "They are learning from us, but we are learning from

them."

Kroger spent years negotiating with Instacart Inc. before

Amazon's Whole Foods purchase spurred executives to strike a deal.

Instacart now makes deliveries from more than 1,600 Kroger

stores.

Some suppliers give Kroger executives credit for acknowledging

the challenges they face. Last year, one grocery-delivery vendor

told a Kroger technology executive that despite the company's

investments in automated online warehouses, it still wasn't getting

digital orders to customers as fast as its competitors.

The executive agreed, according to a person familiar with the

conversation. To figure out how to make same-day deliveries, he

told the vendor, Kroger might need to make another acquisition.

As the company tries to change, some senior executives are

leaving. Mr. Schlotman is retiring after more than three decades at

the company. Christopher Hjelm, the chief information officer who

urged fellow executives to help him turn Kroger into "a technology

company that just happens to sell food," is also departing. Matt

Thompson, the digital official who devised many of Kroger's online

pickup and delivery strategies, left earlier this month. Investment

banker Robert Beyer is stepping down as lead independent director

in June.

A Kroger spokeswoman said the retirements were long planned. Mr.

McMullen has recruited new officials with technology experience at

the executive and board levels, she said.

Executive bonuses have declined in the past two fiscal years,

reflecting Kroger's weaker sales. Financial filings show that

executives hit less than 4% of their targets for performance-based

bonuses in the last fiscal year, the lowest payout in at least two

decades.

Mr. Cosset, the chief digital officer who is set to succeed Mr.

Hjelm as chief information officer in May, has set ambitious time

lines for opening online-pickup locations and other goals. Yet he

has also been careful not to drift too far from Kroger's focus on

its stores.

"The traditional brick-and-mortar customer shouldn't feel

neglected," he said.

Write to Heather Haddon at heather.haddon@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

April 22, 2019 02:47 ET (06:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

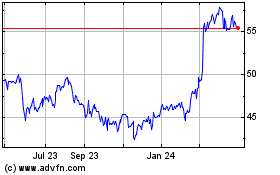

Kroger (NYSE:KR)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Kroger (NYSE:KR)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024