It was once America's most valuable company, the maker of power

turbines, jet engines, TV shows and MRI machines. Fueled by a

relentless optimism, it made and remade itself countless times.

This is the story of how General Electric lost power.

By Thomas Gryta and Ted Mann

This article is being republished as part of our daily

reproduction of WSJ.com articles that also appeared in the U.S.

print edition of The Wall Street Journal (December 15, 2018).

They came by the dozens in luxury sedans, black Ubers and sleek

helicopters. As they did each August, General Electric's most

important executives descended on a hilltop above the Hudson River

for their annual leadership gathering.

Just an hour's drive from New York City or a short flight from

Boston, Crotonville, N.Y., is the home of GE's management academy,

famed for culling and cultivating a cadre of leaders the company

saw as its most valuable product.

Crotonville is where Jack Welch, GE's larger-than-life former

chief executive, held his lecture sessions in "The Pit," a large

sunken auditorium where he coached the future CEOs of companies

such as Boeing and Home Depot. Welch remade and expanded the campus

during his two decades running GE.

Opened in 1956, the 60-acre property is half conference center,

half country retreat. Behind a guard house lolls a mix of low-slung

brick residence halls, classroom buildings and restaurants, a

fieldstone plaza with a fireplace, hiking trails and a helipad.

Welch and other GE bosses would visit nearly every month to lead

programs for middle managers, customers and executives from other

companies who wanted to learn the GE leadership magic. For the

300,000 people who work at GE, a trip to Crotonville is an ardent

desire and a treasured accomplishment.

This pilgrimage in August 2017 was different. The stock price

had been slumping, and longtime CEO Jeff Immelt had just stepped

down after a frustratingly middling 16-year tenure. The new boss,

John Flannery, had started a monthslong review of every corner of

America's last great industrial conglomerate.

On that summer afternoon, the auditorium buzzed with whispers of

what was ahead. No one doubted the 125-year-old company's ability

to rise again. It always had.

Then Jeff Bornstein started talking.

The gruff, 52-year-old chief financial officer had lost out on

the top job weeks earlier, but had committed to staying on to help

the new CEO navigate the company's complicated structure.

Bornstein launched into an exhortation: Run the company like you

own it. Be the leaders General Electric bred you to be. You should

all be accountable for every prediction made and every target

missed.

"I love this company," he said. Then, he stopped and took a

breath -- deep and racked. He started again and stopped again. Jeff

Bornstein, the shark-fishing, nicotine-gum-chomping, weightlifting

CFO, was crying.

A Maine native, Bornstein had come to GE after college,

eventually serving as finance chief of the lending arm, GE Capital,

where he helped stave off the worst damage of the financial

crisis.

His rivals within the company found him blunt to a fault,

willing to chastise or demean in public and private. He served as a

counterbalance to Immelt's relentless optimism, and his finance

chops brought him the respect of Wall Street.

If this guy was fighting back tears, something must be seriously

wrong. In the first six months of 2017, GE had earned hardly any of

the $12 billion in cash it projected for the year. It would need at

least $8 billion just to cover the dividends it had promised

stockholders.

The leadership meeting usually left executives refreshed,

reassured that the foundation of GE's success was not the power

turbines or the jet engines so much as the people in that room,

managers groomed in Crotonville who believed they could enter any

industry, anywhere and dominate it.

Now, as they shuffled out after Bornstein's talk, many felt

shock and confusion. The reckoning had been a long time coming, and

it was far from over. GE had defined and outlived the American

Century, deftly navigating the shoals of depression, world war and

the globalization of business. Even when things were at their

worst, its belief in its history and its prowess made it feel

titanic and impregnable. And, yet, unsinkable GE was taking on

water fast.

This article is based on scores of interviews with dozens of

people directly involved in these events. They include current and

former board members, senior executives and employees at GE

headquarters and in its various business units, as well as bankers

and advisers employed by the company, investors in its stock,

customers for its products and corporate analysts who evaluated its

performance.

The reporting also reflects internal GE communications and

documents, including emails, slide presentations and videos.

Publicly available securities filings, court records, transcripts

of meetings and previous Journal articles were also used. The

Journal reached out to the individuals in this article and offered

them the opportunity to comment.

THE ENGINE ROOM

General Electric Co. helped invent the world as we know it:

wired up, plugged in and switched on. Born of Thomas Alva Edison's

ingenuity and John Pierpont Morgan's audacity, GE built the dynamos

that generated the electricity, the wires that carried it and the

lightbulbs that burned it.

To keep the power and profits flowing day and night, GE

connected neighborhoods with streetcars and cities with

locomotives. It soon filled kitchens with ovens and toasters,

living rooms with radios and TVs, bathrooms with curling irons and

toothbrushes, and laundry rooms with washers and dryers.

The modern GE was built by Jack Welch, the youngest CEO and

chairman in company history when he took over in 1981. He ran it

for 20 years, becoming the rare CEO who was also a household name,

praised for his strategic and operational mastery.

Welch, short, sharp and volatile, had an intense glare and a

reedy growl that betrayed his blue-collar Massachusetts roots. He

was obsessive about setting targets and hitting them. A chemical

engineer by training, he once blew the roof off a GE factory.

He expressed disdain for GE's bureaucracy from his earliest days

there and later earned the nickname "Neutron Jack." He eliminated

some 100,000 jobs in his early years as CEO and insisted that

managers fire the bottom 10% of performers each year who failed to

improve, in a process that became known as "rank and yank." GE's

financial results were so eye-popping that the strategy was

imitated throughout American business.

"Fix it, close it or sell it" was a favorite slogan. Welch

wanted to get out of any businesses where GE wasn't a market

leader.

At its peak, General Electric was the most valuable company in

the U.S., worth nearly $600 billion in August 2000. That year, GE's

third of a million employees operated 150 factories in the U.S.,

and another 176 in 34 other countries. Its pension plan covered

485,000 people. With nearly 10 billion shares outstanding, GE was

also among the most widely owned stocks. The company paid dividends

to more than 600,000 accounts, from individual investors to major

mutual funds that served millions.

GE had moved in and out of businesses since 1892: airplane

engines, plastics, cannons, computers, MRI machines, oil-field

drill bits, water-desalination units, television shows, movies,

credit cards and insurance. The big machines were always GE's

beating heart. But it was a willingness to expand into growing

businesses and shed weaker ones that helped make it the rare

conglomerate to survive the mass extinction of its rivals.

The catalyst for GE's success during Welch's reign was that it

worked more like a collection of businesses under the protection of

a giant bank. As the financial sector came to drive more of the

U.S. economy, GE Capital, the company's finance arm, powered more

of the company's growth. At its height, Capital accounted for more

than half of GE's profits. It rivaled the biggest banks in the

country, competed with Wall Street for the brightest M.B.A.s and

employed hundreds of bankers.

GE Capital sucked in debt and spat out money. Created in the

first half of the last century to help people buy home appliances,

it now financed fast-food franchises, power plants and suburban

McMansions, and leased out railroad tank cars, office buildings and

airliners. The industrial spine of the company gave GE a AAA credit

rating that allowed it to borrow money inexpensively, giving it an

advantage over banks, which relied on deposits. The cash flowed up

to headquarters where it powered the development of new jet engines

and dividends for shareholders.

Capital also gave General Electric's chief executives a handy,

deep bucket of financial spackle with which to smooth over the

cracks in quarterly earnings reports and keep Wall Street happy.

Sometimes that meant peddling half a parking lot on the final day

of a quarter, or selling a part interest in a power plant only to

purchase it back after the quarter closed.

Many Capital veterans relished their reputation as mavericks and

cowboys, especially in comparison to their staid Wall Street

rivals. They loved the story about Capital's then-CEO Gary Wendt

renting a camper and driving across Eastern Europe in the early

1990s, buying up still sleepy banks as the post-Communist era

dawned. The rest of the decade saw explosive growth, helping drive

Jack Welch's fame into orbit.

With shares trading above $150 in early 2000, Welch split the

stock 3-for-1. It would prove to be a high-water mark. GE shares

retreated in his final year after a failed takeover of rival

Honeywell and the popping of the dot-com bubble. Still, GE shares

were trading at 40 times its earnings when Welch retired in 2001,

more than double where it had historically. And much of those

profits were coming from deep within Capital, not the company's

factories.

Disaster hit immediately after Welch left. The Sept. 11

terrorist attacks -- four days after his handpicked successor, Jeff

Immelt, took over -- hammered GE's insurance businesses and

grounded the airline industry. Immelt began revamping the Welch

portfolio, selling off the plastics division and most of the

insurance lines. He didn't rein in the lending at Capital, which

accounted for 38% of GE's revenue in 2008.

When the financial crisis hit, Capital fell back to earth,

taking GE's share price and Immelt with it. The stock closed as low

as $6.66 in March 2009. General Electric was on the brink of

collapse. The market for short-term loans, the lifeblood of GE

Capital, had frozen, and there was little in the way of deposits to

fall back on. The Federal Reserve stepped in to save it after an

emergency plea from Immelt.

After that, GE wasn't regarded like its fellow industrial

companies -- big, slow-moving businesses that could project demand

for their hulking machines over decades. Instead, the near-death

experience taught investors to think of GE like a bank, a stock

always vulnerable to another financial collapse.

Bank supervisors from the Federal Reserve moved into a suite of

offices in Capital's headquarters just off the Merritt Parkway in

Norwalk, Conn. They hovered in meetings, demanding details on

lending businesses that Capital staff worried the regulators didn't

understand or respect.

Immelt gritted his teeth at the name of Caroline Frawley, head

of the Fed teams that patrolled the unit that spun out nearly half

of GE's profits.

"That woman," he said at one point, "is not going to tell me how

to run this company." He wanted to be free to invest billions into

developing a new jet engine without worrying about the government

looking over his shoulder.

As the recovery slouched into the early part of this decade, a

handful of top-ranking executives huddled here and there, always

discreetly, to discuss their most obvious problem. GE couldn't live

without GE Capital, still so big it was essentially the nation's

seventh largest bank. But investors couldn't live with GE Capital

and its unshakable shadow of risk, either.

What if the GE Jack Welch built didn't work any more?

GE might reap billions from selling Capital's businesses, as

well as the real estate, mortgages and other assets it owned, but

that would create a gigantic tax bill. More importantly, the

company would need a plan to replace the earnings Capital brought

in each quarter.

Cracks in the performance of the company's industrial lines --

its power turbines, jet engines, locomotives and MRI machines --

would now be plain to see, some executives worried, without

Capital's cash to help cover the weak quarters and pay the

sacrosanct dividend. That dividend, doling out billions of dollars

to shareholders, is one reason GE was owned by so many, with about

43% of its shares held by individual investors.

It was hard to see how the puzzle pieces could be made to fit.

Immelt and Bornstein, the CEO known as Big Jeff and the CFO as

Little Jeff, and a small group of trusted lieutenants, kept

meeting.

Increasingly, Immelt worried about his legacy. He often reminded

people that he kept the ship afloat after Sept. 11 and the

financial crisis. But he also joked that his ability to ride out in

a blaze of glory ended the day Lehman Brothers went bankrupt in

September 2008.

Whittling away at Capital wasn't enough. Immelt, trapped in

Welch's long shadow, craved a bold move to shock his company out of

the doldrums that had plagued his tenure. It was time for GE to be

reinvented again.

MEAL AND DEAL

Jeff Immelt was on his way to the Winter Olympics in Russia in

February 2014 when the GE jet made a stop in Paris for dinner. He

had an invitation from Patrick Kron, his counterpart at the

struggling French industrial conglomerate Alstom SA.

Kron was looking for a savior. Alstom, a maker of trains, rail

equipment, power turbines and generators, was veering toward

insolvency, signing up business at a loss just to keep money coming

in the door. The beleaguered CEO had dined already with the chief

executive of GE's archrival, Siemens AG. In Immelt, Kron found a

man spoiling for a big deal.

Just a few months earlier, the word had gone out to the merger

teams embedded in each of GE's industrial units: Headquarters wants

your biggest targets.

Alstom was one of the expensive deals Immelt focused on as the

two CEOs chatted into the night in Paris. After dinner in France,

Immelt stopped in Helsinki to consider another target, Wartsila, a

Finnish builder of marine engines, oil-and-gas equipment and power

plants. Another potential deal, dubbed Project Lion, came from GE's

oil-and-gas unit. Still, not long after the restaurant bill was

paid, momentum was building for a bid on Alstom. The only question

was how much Immelt would be willing to pay.

Some GE directors and advisers were wary. Immelt's determination

to complete a blockbuster reflected his customary optimism, a trait

that had led him to overpay in the past, and one the succession

team warned the board about before it picked him as CEO.

Hardworking and affable, Immelt was 6-foot-4 with a mane of

graying hair swept back from the temples. He moved easily through

crowds and possessed the practiced eye contact of a politician. He

was quick to chuckle and usually had a joke to tell, even if it

often was one he'd already told.

Former colleagues compared him to Bill Clinton because of his

magnetic ability to hold the focus of a room. He sounded like a

leader. He was a natural salesman.

Immelt, an Ohio native who played football at Dartmouth, came to

GE out of Harvard Business School. He changed jobs often, working

in the plastics division before eventually running the health-care

unit. Immelt was 44 years old when he won a bruising and public

succession contest set up by Welch, beating out two men who would

later lead Home Depot, Chrysler, 3M and Boeing.

Welch advised him to carve his own path, and Immelt's decision

was to take a gentler tack. Welch was known to put his arm around

an executive who just missed his numbers, tell him he loved him and

if it happened again, he was out. Immelt could lean on executives

and their underlings just as hard, cajoling and challenging, but he

discouraged dissent by applauding optimistic news.

Welch, the engineer, was likely to quiz a manager about details

-- why are the numbers down at your plant -- where Immelt dealt in

broader strokes. He embraced his background in sales. A

presentation at any GE meeting was called "a pitch" and ideas for

new businesses were "imagination breakthroughs." Decisions had to

fit with the "story" of the company and where it was going.

Immelt was so confident in GE's managerial excellence that he

projected a sunny vision for the company's future that didn't

always match reality. He was aware of the challenges, but he wanted

his people to feel like they were playing for a winning team. That

often left Immelt, in the words of one GE insider, trying to market

himself out of a math problem.

For the month or so after the dinner with Kron, a team of GE

merger specialists set about trying to make the math for the Alstom

deal work.

Executives at GE Power knew Alstom well, having given it an

appraising sniff two years earlier. They found a company then too

troubled to take a run at: Alstom was in greater need of cash than

the market understood, had too many employees and French law made

it too difficult to lay off workers and sell assets.

Alstom's problems hadn't gone away, but now its stock was

cheaper, and Immelt saw the makings of a deal that fit perfectly

with his vision for reshaping his company. GE would essentially

swap Capital, the cash engine that no longer made sense, for a new

one that could churn out profits each quarter in the reliable way

that industrial companies were supposed to.

At the time of GE's 2014 shareholder meeting in April, Alstom

executives flew to a hotel near the venue in Chicago to talk. To

the dismay of some involved, GE's bid crept upward, from the EUR30

a share that the power division's deal team already believed was

too high, to roughly EUR34, or almost $47. Immelt and Kron met

one-on-one, and the deal team realized the game was over. The

principals had shaken hands.

Immelt knew Alstom had its problems but hoped to show off the

management prowess on which GE prided itself. The French company

had a large collection of power plants that GE would run more

efficiently and a flabby global workforce that GE would slash.

News of the deal leaked hours after the shareholder meeting was

over. Valued at $17 billion, the acquisition would be GE's largest

ever and the first move in the one-two combination that Immelt

thought would revive his company and set his legacy.

THE PIVOT

Jeff Immelt was all smiles when he took the stage for that

August's annual Crotonville leadership summit.

His first PowerPoint slide was entitled "GE Pivot." Alstom

promised "tremendous upside with strong execution," read another

projected on the auditorium's big screen. "Unique & historic

opportunity at high returns."

In Immelt's vision, this was a chance to corner the market on

lighting the unlit corners of the Earth. He imagined crushing

competitors for gas-fired power turbines such as Germany's Siemens

and Japan's Mitsubishi, and winning bids to build power plants

across the Middle East, Africa and South Asia. In the present, the

deal made sense to other GE executives because they believed the

company could squeeze more profit from the old, coal-fueled power

plants Alstom operated in Europe and Asia.

The visions for the present and the future were both

fundamentally flawed.

As GE's research department was preparing white papers heralding

"The Age of Gas," the world was entering a multiyear decline in the

demand for new gas power plants and for the electricity that made

them profitable.

Opposition from the French government -- blindsided when news of

the deal leaked in April -- slowed completing it to a crawl. GE's

negotiating team continued to agree to more costly concessions

demanded by regulators on both sides of the Atlantic as 2014 bled

into 2015.

Under pressure from the U.S. Justice Department, GE agreed it

would get rid of an Alstom unit that serviced turbines made by

competitors.

Bowing to the Europeans, GE agreed to dump Alstom's

still-developing program to build a state-of-the-art gas turbine

equivalent to GE's flagship model. That technology was transferred

to Italy's Ansaldo, potentially opening the door to more serious

competition since the company is 40% owned by the Chinese. And

European and Alstom officials stymied GE's attempts to review the

company's order book: a black box of immeasurable risk since the

French company had been lowballing bids just to keep sales coming

in.

By mid-2015, the concessions threatened GE's logic for the

acquisition. The company hired litigators at one point, ready to

fight regulators, or even to help extricate GE from the deal, if

Immelt and his top executives decided it no longer made sense.

A band of skeptics inside GE Power were hopeful the deal would

collapse. When advisers determined that the concessions to get the

deal approved might have grown costly enough to trigger a provision

allowing GE to back out, some in the Power business quietly

celebrated, confiding in one another that they assumed management

would abandon the deal.

But Immelt and his circle of closest advisers wanted it done.

That included Steve Bolze, the man who ran it and hoped someday to

run all of General Electric.

THE EXIT

In the early spring of 2015, GE Capital's chief, Keith Sherin,

strode into a colleague's office in the division's Norwalk

headquarters to share the company's most tightly held secret.

"We're going to de-SIFI," the boss said.

That mystifying bit of regulatory jargon could only mean one

thing: They were selling GE Capital. Immelt's reinvention of GE was

moving into its next phase.

In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, Capital was

deemed such a big player in the banking system that it was

designated a "Systemically Important Financial Institution" and

forced to accept the more intrusive regulation that Immelt so

despised. In the years since, GE Capital had been shrinking slowly,

but not fast enough for investors.

To get out from under the Fed's thumb, GE would sell $216

billion worth of financial assets -- real estate, railcars,

mortgage holdings and lending operations that served midsize firms

and provided venture capital. Added to what it had already spun

off, $310 billion worth of Capital's business would be chopped up

and spread across the American financial system. That would leave a

$100 billion stub that included the plane-leasing unit and some

industrial leasing operations meant to boost GE's power and

oil-and-gas businesses.

Once complete, less than 10% of GE's total earnings would come

from the finance engine that Jack Welch had built.

It struck some within Capital as an overcorrection to both the

markets and skeptical regulators at the Fed. Some worried how the

company would manage once most of GE Capital was gone.

"What are we going to do about the cash?" the second Capital

executive asked after Sherin broke the news.

"We'll work it out," Sherin said, thinking ahead to the

thousands of hours and hundreds of people it would take to pull

off. Immelt had picked Sherin, who had been the finance chief of

the entire company, to run Capital after the financial crisis.

Their idea was to use the proceeds from selling most of Capital

to buy back GE shares, offsetting the loss of Capital's

earnings.

The company made the plan public on April 10, almost one year

after the Alstom deal leaked to the press, and decided to act fast

to sell most of the business. Despite a few private misgivings in

Norwalk, the plan was widely supported by other GE employees, the

board and, more importantly, investors.

Billionaire Nelson Peltz, who runs Trian Fund Management, an

activist investment firm feared by executives of struggling

companies, called to congratulate Immelt on the pivot right after

the announcement.

In response, the GE boss told Peltz: "We'd love to have you in

the stock."

CRACKS IN POWER

Things were beginning to come together for Jeff Immelt as 2015

wore on. That summer he sat behind a desk in the auditorium in

Crotonville watching Steve Bolze cue up PowerPoint slides as part

of the Growth Playbook, a grueling annual examination of GE's eight

business leaders.

At the event, GE would hammer out targets for sales and profit,

setting the underlying assumptions for the financial estimates it

would give investors.

It had been a few months since the plan to sell off GE Capital

had been announced, and Bolze, the head of GE Power, was inching

toward completion of the Alstom deal.

Already the chief of GE's largest business by sales, Bolze, 52

years old and square-jawed, was in the race to succeed Immelt, and

he was about to add a huge new global portfolio of power plants and

thousands of workers to his fiefdom.

Moving through the slides, Bolze came to the proposed annual

sales growth rate of the power business: 5%.

There was ample reason for skepticism. Power had been struggling

to meet targets, and its sales hadn't grown that quickly in years.

Global investment in new gas-fired power plants was slowing. Energy

efficiency was on the rise. That meant future revenue from the

highly profitable service contracts GE had signed was likely to

fall, or at least to grow less quickly. Global gross domestic

product, a reliable proxy for the power market, was below 4%.

It was a rosy assumption that cried out for interrogation, the

very point of the formal review. As the room watched, Immelt gave

the desk in front of him a confident slap.

"Great, next page," he said.

Immelt could be tough on executives in his own way in these

briefings, but it wasn't usually for being too optimistic. "Where's

the guy I used to know?" he would ask an underling who told him

Immelt's targets couldn't be hit. When the mood soured, the tone

changed. "Your people," Immelt would say, "don't want it bad

enough."

So, they stretched. This was particularly true in Power after

the Alstom deal closed in November 2015. Immelt pushed for market

share at all costs, which led to less than lucrative deals. They

also used financing from the stub of GE Capital to help prop up

customer demand.

Already facing a slowdown in equipment sales and competition

from renewable energy, managers in Power struggled to mesh their

operations with Alstom's, the largest effort of its kind in GE

history.

Throughout 2016, teams inside Power combed through the portfolio

of service contracts, each representing payments from power

generators to maintain the turbines GE had sold them. By design,

those contracts were malleable. A technological innovation that

improved the performance of a turbine blade or lengthened the

number of hours between maintenance outages had to be accounted

for.

The GE teams started offering discounted turbine upgrades to

customers in exchange for extending the length of contracts to as

far out as 2050. Executives scoured existing contracts for ways to

change underlying assumptions, such as the frequency of overhauls,

to boost their profitability.

GE Power even sold its receivables -- the bills its customers

owed over time -- to GE Capital to generate short-term cash flow.

The unit gave customers discounts on their service contracts,

lowering their overall value, in exchange for renegotiations that

let the company bill the customers sooner.

The accounting maneuvers were legal, if aggressive, GE

executives assured one another. But it also meant that the profits

were mostly on paper. Rarely was a new dollar of profit flowing in

the door.

Bolze's team was operating in a tradition that stretched at

least as far back as the glory days of Jack Welch, but the scale of

the aggressive contract accounting was far bigger.

Worry was starting to grow inside Power by the end of 2016.

Management's expectations about the sales growth and profit they

should be able to hit didn't reflect the dim reality of the market,

team members told Bolze and Paul McElhinney, the head of the unit

that administered the service contracts.

The complaints were common among lower-level executives, but

when raised to leaders like McElhinney, they were stopped cold.

"Steve's our guy," McElhinney said in one meeting. If Bolze was

elevated to CEO, those behind him in Power would rise too. "Get on

board," he said. "We have to make the numbers."

ENTER TRIAN

The seed Jeff Immelt sowed with his invitation to Nelson Peltz

bore fruit in the fall of 2015. Trian Fund Management disclosed it

had been secretly buying up GE shares, amassing a stake worth $2.5

billion that made it one of GE's 10 largest shareholders.

Some outsiders saw Immelt inviting in a disruptive investor like

Peltz as a sign of confidence, but it was also a defensive

strategy. Other activists were circling GE.

Activist investors are usually bad news for managers. The pools

of shares they control provide a fulcrum for prying loose board

seats, management changes and the sale of businesses.

Trian wasn't calling for a breakup or CEO change, though, as it

had at lumbering companies including DuPont and Kraft. It wasn't

even seeking a seat on GE's board, whose 18 high-powered members

were loyal to Immelt, as it had at Family Dollar, Ingersoll-Rand,

Mondelez International and PepsiCo.

Rather, the influential hedge fund was coming forward with what

amounted to a high-profile endorsement of Immelt's strategy.

Trian's co-founders, Peltz and his son-in-law Ed Garden, took

care to say this was a partnership with GE and its brass. The duo

traveled to GE's Fairfield headquarters on a Sunday afternoon to

explain their thinking. They sat alongside Immelt and Jeff

Bornstein, the GE chief financial officer, under oils and

watercolors, many of them the spoils of Jack Welch's ill-starred

purchase of the brokerage Kidder-Peabody.

"It's not something you want to break up," Peltz said inside the

wood-paneled boardroom. "It's something you want to keep taking

care of."

Trian didn't like to be called an activist investor, even though

it helped revolutionize that corner of the investing world,

preferring to be called an engaged shareholder. While it built a

reputation as a conglomerate killer, it had found a conglomerate it

liked in GE.

An 80-page white paper that Trian released with its investment

was titled "Transformation Underway...But Nobody Cares." It argued

GE's stock, then around $25, could reach $40 to $45 by the end of

2017. It praised the Alstom deal and pushed GE to borrow more so it

could repurchase another $20 billion in stock.

Running the GE relationship fell to Garden, a 57-year-old,

hard-charging financier who knew both Immelt and Bornstein. In

fact, Garden's brother had been a college buddy of Immelt.

Garden, a lean man fond of clear-rim eyeglasses, was the calmer

side of the partnership with Peltz. He had little problem speaking

his mind, though, making clear Trian helped fix companies -- and

also break them up.

It didn't take more than a few months for the good feelings to

sour. Trian said at the outset it would be watching GE's

performance. A year after the initial investment, GE was behind on

financial targets and the stock wasn't moving.

In the fall of 2016, an increasingly impatient Garden went to

see Bornstein at his six-level, $13 million townhouse in Boston's

Back Bay. Garden said if the performance didn't improve, Trian

might ask for a seat on the board. The threat of a public battle,

which GE wanted to avoid, gave Trian the leverage it needed.

The two men started to work out a compromise. GE doubled its

cost-cutting goals and tied more of its executive bonuses to

profits at its core industrial units.

Some parts of the agreement weren't public. If GE didn't get

back on track, Trian would push a board seat or management changes.

Both men understood that could include Bornstein himself, a man

many within the company thought had the best chance to succeed

Immelt.

TROUBLE IN SARASOTA

Jeff Immelt wasn't backing down on GE's strategy or direction.

The company was a market leader, it validated trends and set the

tone for other companies. It didn't run away from problems.

After President Trump's election and threat to pull the U.S. out

of multinational trade deals, Immelt used his annual letter to

shareholders in February 2017 to remind them that GE was bigger

than any one country.

"We don't need trade deals, because we have a superior global

footprint, " he wrote. "We see many giving up on globalization;

that means more for us."

During a time when many companies were trying to avoid attention

from the new president, Immelt didn't shy away when Trump's

deregulation agenda conflicted with GE's stance on climate

change.

"No matter how it unfolds, it doesn't change what GE believes,"

he wrote in a note to employees in March 2017.

GE was still on the muscle, hunting for big deals. A team in the

aviation division had worked with bankers to put together a

proposal to buy aerospace rival Rockwell Collins in late 2016. The

deal pitch, worth more than $15 billion, reached Immelt in early

2017. He scuttled it. Instead, GE kept repurchasing stock, spending

more than $3 billion in first four months of 2017.

GE Power, the unit that led all others in sales, was the

centerpiece of Immelt's new GE. But there were only so many service

contracts to be renegotiated.

The company revealed the weakness hidden inside the unit that

April with a single, startling figure: GE's industrial businesses

were sending $1.6 billion more out the door in the first quarter

than was coming in, about $1 billion worse than it had projected.

The result raised red flags about aggressive accounting and whether

the company could make its goals.

Most of the shortfall came from its service contracts, which

should have been the source of the easiest profits. Instead, the

heart of the industrial business was hollow. And its failure was

about to tip the entire company into crisis.

Immelt only had a month before the Electric Products Group

conference, a sort of national convention for the industrial

fraternity. As the head of the biggest U.S. conglomerate, the GE

chief was traditionally the star attraction, holding court and

giving the keynote presentation to close the three-day meeting.

GE's shares were down 11% so far that year, missing out on a

broad market rally that had seen the S&P 500 climb more than

6%. Investors openly wondered if Immelt would stick by his 2018

profit target of $2 a share. Senior executives were perplexed about

the long-held target, and Jeff Bornstein, the CFO who had given his

word to Trian at risk of his job, advised against sticking to

it.

Immelt was an accomplished presenter, his ability to navigate a

deck of PowerPoint slides honed over the decades. This year was

different. The confident, affable salesman ready with a smile and a

joke wasn't himself as he faced a skeptical audience inside the

ballroom of the Longboat Key Resort in Sarasota, Fla.

He was shaky, racing through the highlights of his slides. On

the last one, he defended the company's 2018 profit goal. Sort of.

If the oil and gas markets didn't improve, he said, the $2 target

for 2018 would be a reach, and the company would have to cut even

more costs.

Immelt, with his eye on the future, believed the next CEO would

eventually have to reset the goal, and Immelt thought cutting the

target twice would be bad for investors and the company.

The crowd buzzed with confusion. Barclays analyst Scott Davis

asked bluntly if Immelt was backing the target.

"It's going to be in the range, Scott," Immelt said. "If we

wanted to take it off the page, we would have taken it off the

page. We didn't want to."

The questions didn't get better. Is the Alstom deal not working?

Can the power division improve its cash flow? Would the company

consider spinning off the health-care division that Immelt had once

run?

Immelt, as he had before, argued that investors had GE all

wrong, mispricing a stock that should have been above $30 a share.

The aviation business was booming, outpacing competitors with its

newest model. The once-troubled health unit was on the upswing. The

oil-and-gas business, which had suffered through sliding crude

prices, was riding a rebound.

"It's not crap. It's pretty good, really," Immelt said of his

company's financial performance.

When the grilling was over, Immelt wasted no time getting out of

Sarasota. In less than an hour he was aboard a GE jet. Immelt, his

credibility wounded with Wall Street, limped through the rest of

the week as frustrated investors called seeking clarity on the

state of the company.

Trian, which had recently projected that GE could actually

exceed the 2018 goal Immelt had waffled on, made it clear it was

going to push for a seat on the board.

All of a sudden, a question that Immelt had batted away with

little more than a joke during the questioning in Florida seemed

significant.

"Hate to put you on the spot," said Steve Tusa, an analyst from

JP Morgan Chase & Co. who had been telling investors to sell GE

shares, "but I'd like to get any update on succession planning,

potential time. I know you just can't bear the thought of not

coming down to Sarasota."

AFTER IMMELT

Only a dozen men had led General Electric to this point in its

history. Many spent a decade in the role. Jack Welch spent two.

Jeff Immelt was in his 16th year. He had tried everything to

revive the stock, but in the days after his struggles in Sarasota,

he realized he had lost the confidence of investors, especially

Trian. Without that, the optimist saw little chance he could lead a

turnaround.

Immelt decided it was time for a change, and he wanted to do it

without being pushed.

GE didn't take replacing its CEO lightly. When Immelt competed

for the top job, candidates were moved around, performance was

measured, the list was narrowed and those passed over often left.

Corporate governance experts praised it at the time as the very

model of a modern chief-executive succession.

The process left Immelt with a sour taste. For years he was

clear he wanted his own successor picked in a less public contest,

and was true to his word.

The board years earlier had quietly set a target of late 2017

for a new CEO to take over and identified four GE men as possible

successors: Bornstein, the finance chief; Bolze, the head of the

power division; John Flannery, the leader of the health-care unit;

and Lorenzo Simonelli, boss of the oil-and-gas business.

In May 2017, around the same time of Immelt's disastrous

performance at the conference, the board called the candidates to

New York to audition. But by that time, the secret race had already

been won. Flannery was the unofficial heir apparent.

Simonelli, seen at 45 as too young for the main job, was

ticketed to run the public company that resulted from the merger of

GE's oil-and-gas unit and oil-field service company Baker

Hughes.

Bolze, whose team at Power had stretched so far in hopes of

riding his coattails, was out. Not only was his unit the sclerotic

heart of GE's struggles, but Bolze, who had occasionally clashed

with Immelt, was seen early in the process as a poor fit as

CEO.

Bornstein hadn't run a GE business unit before, and Immelt and

the board felt he could be a better partner to a successful

candidate, if he would agree to stay on.

The process was shrouded in secrecy up until the end. After

Immelt informed the board of his intention to step down, a small

staff worked out of human-resources chief Susan Peters' apartment

to write the press release and other materials for the

announcements.

A 30-year GE veteran, Flannery had yet to be told he had won the

job. On Friday, June 9, less than three weeks after the Sarasota

conference, Flannery got a call. Immelt was out. He was in.

Bald and bespectacled, Flannery was nothing like Immelt. He was

soft-spoken and analytical. More accountant than salesman, he

lacked Immelt's booming presence and charisma.

Flannery was Trian's ideal successor, a balm for its

frustrations with Immelt. He had an investor's mind-set, crunched

numbers naturally and was obsessed with the cash businesses

produced.

Flannery, whose father was president of a small Connecticut

bank, spent most of his years at GE Capital after getting his

M.B.A. from Wharton. He worked in risk management, private equity

and eventually rose to be the head of mergers and acquisitions. He

had spent years imagining a more streamlined GE and was bewildered

by its inability to meet cost-cutting targets.

For some, that made him dry. For others, including the GE board,

he was just what GE needed. He knew of Immelt's flaws and wanted to

change the culture to encourage debate and focus. Some of Immelt's

signature endeavors and buzzwords evaporated when Flannery

ascended.

It was tempting to cast him as the anti-Jeff, but he was

instrumental in the Alstom deal, arguing it would be a valuable

asset.

Flannery was also a GE die-hard, just as his predecessor and his

rivals for the job. Flannery told associates after taking over that

he kept a "f -- you list" bearing the names of those who had done

GE wrong, especially those who left the company.

A SHORT HONEYMOON

John Flannery didn't waste any time. Even before he was supposed

to officially start as CEO in August, he launched a review of each

business unit, scuttled a futuristic building planned for the new

Boston headquarters, and grounded the fleet of corporate jets that

Immelt had used so extravagantly that he had a spare plane follow

him around the world. Each Friday, even if Flannery was on business

overseas, he answered employee questions in a recorded video,

helping to boost spirits.

He also made a pilgrimage to Nantucket to see Jack Welch, then

81, who has a house there. Some expected Flannery to be more like

Welch and less like Immelt; in the aviation division some workers

were walking around chanting "Jack is back." The enthusiasm was

double-edged, an endorsement of Flannery and a rebuke of

Immelt.

The honeymoon didn't last long. Flannery was expected to make

things better, but he revealed in his first conference call in July

that he wouldn't lay out his strategy until November. Investors

used to Immelt's optimism were left mired in uncertainty. GE's

stock dropped nearly 3%, to $25.91 a share.

Flannery soon learned that things were worse inside GE Power

than he had known. The service contracts tweaked when Steve Bolze

was in the running for CEO made earnings look better on paper, but

delayed money coming in. Factories were holding a glut of expensive

inventory because the division had prepared for growth into a

market that was collapsing, tying up more cash.

The mess in Power led to the abrupt departures of key GE

veterans, a move some inside the company worried would leave the

rookie CEO short of experienced hands to help revive GE's

fortunes.

Bolze had left soon after losing the CEO competition. The

secrecy of the succession race meant there wasn't another leader

ready to step in at Power. It was still integrating the company's

largest-ever acquisition and about to enter one of the biggest-ever

slumps in the power-generation market.

Immelt, who had stayed on as chairman, didn't stick around for

the new CEO to dismantle what he had built. He left the company

where he had spent most of his life in October, months earlier than

expected. A few days later, Flannery nudged out Immelt's top

lieutenants, marketing chief Beth Comstock and international

business head John Rice.

As the board was gathering in October for a monthly meeting,

Flannery stepped into the room to make an announcement: Bornstein,

the company's hard-nosed CFO, was resigning. Bornstein himself

later came in to explain his decision. They were likely to have to

offer Trian a seat on the board. Leaving now might spare directors

some conflict between Trian and management. Bornstein would depart

along with Comstock and Rice.

It blindsided several directors, leaving them disappointed the

board hadn't been consulted. They felt they could have persuaded

Bornstein to stay on. The CFO's resignation caused more worry from

investors. GE announced Bornstein's departure after the market

closed on a humdrum Friday.

The next big news wasn't long in coming, and this time it

involved addition instead of subtraction. That Monday, GE named

Trian's Ed Garden to its board, a move months in the making after

the company failed to hit the targets Bornstein had agreed to in

his Back Bay townhouse. Investors drove down GE stock almost 4% to

$23.43 by the time the market closed.

Flannery and the board, wanting to avoid a proxy fight, added

Garden without opposition. Some directors welcomed the new voice,

even if Garden could prove abrasive at times, while others on the

board were blunt in declaring their distaste for him.

Garden was fond of reminding them all that Trian had lost

hundreds of millions of dollars on their watch. Now, he had a

direct say in decisions and access to all of GE's financial

secrets.

THE ANTI-JEFF

If Jeff Immelt was known for his vaulting optimism, John

Flannery quickly became known for his boundless brooding.

Few decisions, even major ones, were final as he devised the

strategy he promised to unveil in November. Flannery relentlessly

sought input from outsiders, searching for flaws in his reasoning.

The feedback meant a decision, like selling off a division, could

be reassessed at any time.

He repeatedly conferred with the board and encouraged debate.

Under Flannery, the board or its committees had dozens of meetings

and conference calls. In just one year, they got together in one

way or another 50 times.

Flannery felt more analysis and scrutiny was exactly what GE

needed. Too often, the company under Immelt had made major

decisions about how to spend its cash without enough rigor. And

because of GE's decentralized structure, Flannery felt he needed

time to better understand the disparate units despite his three

decades working at GE.

The whole process, invigorating at first after Immelt's dislike

of dissent, quickly became grating to the top executives.

By the time the third-quarter results came in October, the stock

was below $25 and losing ground. GE warned that full-year cash flow

from its industrial businesses would now be $7 billion, a shadow of

the earlier guidance of $12 billion. The loss was almost entirely

from the troubled Power division.

With the November date for releasing his strategy to investors

rushing toward him, Flannery was forced to stop agonizing, even

though his plan remained a work in progress.

Hours before several hundred investors, analysts and reporters

packed into a large wood-paneled meeting room in Midtown Manhattan

on Nov. 13, GE disclosed it would cut its dividend in half.

Some of Flannery's explanation was familiar -- he blamed the

previous management of GE Power -- and some of it was new and

unnerving. "We've been paying a dividend in excess of our free cash

flow for a number of years now," he said.

In the dry language of accounting in which he was so fluent,

Flannery was declaring a pillar of Immelt's pivot had failed: GE

had been sending money out the door to repurchase its stock and pay

dividends but wasn't bringing in enough from its regular operations

to cover them. It wasn't sustainable. Buybacks and dividends are

generally paid out of leftover funds.

Flannery warned it would take years to fix some of the company's

businesses and laid out a future for three core markets -- power,

aviation and health care -- while planning to jettison smaller

divisions, such as transportation and lighting.

Despite the wait, there was no radical restructuring, and just

as it had after Flannery spoke in June and in October, the stock

fell. Shares drifted below $20.

Deep inside the disappointing three-hour presentation was a

little-noticed warning from Jamie Miller, Jeff Bornstein's

replacement as chief financial officer: The ghost of an insurance

business that investors thought the company had rid itself of years

before would prevent GE Capital from sending the $3 billion it had

promised to headquarters.

In 2004, GE spun off most of its insurance holdings into

Genworth Financial, and the remainder was largely sold to Swiss

Reinsurance Co. two years later.

Top executives celebrated the move often in public statements.

Immelt said that GE might not have survived the financial crisis if

it hadn't shed the insurance operations, an example he and his

supporters used to demonstrate his astute deal timing.

But when GE spun off Genworth, there was a chunk of the

business, long-term-care insurance, that lingered. Policies

designed to cover expenses like nursing homes and assisted living

had proved to be a disaster for insurers who had drastically

underestimated the costs.

The bankers didn't think the long-term-care business could be

part of the Genworth spinoff. To make the deal more attractive, GE

agreed to cover any losses. This insurance for insurers covered

about 300,000 policies by early 2018, about 4% of all such policies

written in the country. Incoming premiums weren't covering

payouts.

Two months after Miller flagged the $3 billion, it was clear the

problem was a great deal larger. GE was preparing for it to be more

than $6 billion and needed to come up with $15 billion in reserves

regulators required it to have to cover possible costs in the

future. The figure was gigantic. By comparison, even after the

recent cut, GE's annual dividend cost $4 billion.

The company won a waiver from regulators to allow it to build up

the reserve over seven years rather than all at once. The numbers

were dire enough, though, that GE held a special call for investors

in January 2018, only days before it was scheduled to release

earnings.

During the call, Flannery, who had promised in November that his

review had left no stone unturned, said that he would spend some

time -- again -- looking at options for all of the business units.

He carefully avoided using the words "break up," but that's how it

was interpreted: The GE lifer was considering dissolving the

conglomerate. Investors he hoped to placate were unimpressed. GE

shares fell almost 3% to $18.21.

THE BEST PEOPLE

The General Electric board of directors had long been one of the

world's most prestigious corporate appointments.

When Flannery took over as chairman from Immelt, the members

included a dozen current or former CEOs, the dean of New York

University's business school and a former chairman of the

Securities and Exchange Commission.

The 17 independent directors got a mix of cash, stock and other

perks worth more than $300,000 a year, and they also could receive

up to $30,000 worth of GE products in any three-year period. The

company also matched directors' gifts to charity. Upon leaving the

board, a director could direct $1 million in GE money to a

charity.

For 36 years under Immelt and Welch, the board had largely

followed the chairman's lead. One newcomer under Welch was so

surprised by the lack of debate that the director asked a more

senior colleague, "What is the role of a GE board member?"

"Applause," the older director answered.

Immelt, like many CEOs who are also their company's chairmen,

made sure his board was aligned with him. In 2016, he pushed out

Sandy Warner, a 24-year GE director and the former CEO of JP

Morgan, after the two had clashed over Immelt's succession.

Warner thought it should be sped up, and that Steve Bolze, head

of GE Power, was likely the man for the job. Immelt, dissatisfied

with how Bolze was running Power, felt he had to force Warner off

the board to torpedo Bolze.

Warner appealed to fellow directors in a closed session. Would

they at least allow a debate on whether it was time to replace the

CEO? The board stuck with Jeff Immelt, and Sandy Warner walked away

for good. GE told investors in a securities filing he left because

of new term limits and didn't disclose the dispute.

The Federal Reserve, when it was supervising the company, had

urged the board to push back more on Immelt. The CEO often made it

a point to go around the board table to ensure everyone had a

chance to comment on a strategic decision. Directors rarely

challenged him. To Immelt, it was proof he solicited input and

encouraged debate.

Flannery had committed to revamping and shrinking the board

after investors criticized its oversight of Immelt.

Board meetings at GE were an elaborate production. With 18

directors and another dozen regular attendees, the room was packed,

and the agenda was, too. The plan being implemented in the first

part of 2018 called for the board's size to be cut to 12. Half of

the current directors would leave and three new ones would be

added.

Just like previous CEOs, Flannery wanted to make the board his

own, but he wanted more than a rubber stamp for his decisions. He

wanted an active debate. It was one of the reasons he welcomed the

inclusion of Trian's Ed Garden.

He also sought out Larry Culp, the former CEO of smaller

conglomerate Danaher Corp. In the 14 years Culp ran the company

known for its dental implants and medical devices, he had earned a

reputation for tough deal-making and careful spending.

Danaher shares surged during his tenure, and he had retired at

52 years old after making more than $300 million. The company

sometimes came up at GE board meetings as an example of a more

functional conglomerate.

Before Culp joined the board in April, an adviser warned

Flannery that Culp would be the man to replace him atop GE if

things soured. Flannery said he didn't care; he needed the best

people to help him right the listing ship.

BACK TO SARASOTA

Before he was named the boss, John Flannery had enjoyed a

reputation inside of GE for being a calm, confident leader who had

revived GE's health-care business.

Folks liked to point to how he handled a presentation to 700

company bigwigs at GE's annual global management retreat in Boca

Raton, Fla., in January 2015. It was a big deal to be chosen to

talk at the company's ultimate networking event, and the

presentations took weeks to prepare.

Flannery showed up for his without PowerPoint slides and wowed

the audience with his quiet confidence and command.

Three years later, it was clear that being CEO of GE wasn't the

same as presenting at Boca, especially when everyone was looking to

you to save the company. Flannery was building a new reputation. He

lacked self-confidence and sometimes flew off the handle. He could

get flustered in high-pressure situations, and GE's stock price

dropped anytime he opened his mouth.

The Electric Products Group conference was fast approaching in

May in Sarasota, the setting for Immelt's last stand a year

earlier.

Flannery's handlers were prepping him to avoid another setback.

They had a long sheet of possible questions and appropriate

answers. They did mock sessions and asked him the same questions in

many different ways, so he could always steer to the best

response.

Once on stage, the preparation couldn't hide Flannery's

all-too-familiar message. The power business faced years of

struggle and major changes at the conglomerate would take time to

show results.

When pressed, Flannery declined to commit to GE's dividend for

2019. He gave the answer as a finance expert. The dividend will

reflect the ability of the existing portfolio to pay it, so it may

change with the portfolio. If a company sold half its businesses,

it couldn't pay the same dividend.

The transparency was unusual. The CEO playbook called for him to

stand by his commitment to the dividend, until he didn't. Flannery

also defended his methodical approach to his latest review of the

company's businesses.

"So being deliberate and then moving when things make sense as

opposed to moving just because somebody wants us to is just not my

style," he told the crowd. "So, I get that people want faster. I'm

managing in a broader sense."

Flannery had spoken, and the stock had fallen 7%.

THE BREAK UP

It was a measure of the challenges facing John Flannery that

when GE was dumped from the Dow Jones Industrial Average in June,

he had bigger things on his mind.

An original member of the index, GE had been continuously part

of the Dow since 1907. It was replaced by Walgreens Boots Alliance

Inc., a drugstore chain with a market capitalization half as big as

GE's.

It was a blow to GE's battered rank-and-file. Being dropped from

the most widely cited stock index meant they no longer worked at

one of America's 30 most prestigious companies.

Flannery was too busy to lament a move he saw as inevitable. In

a week, he was going to unveil a plan to break up the company

spawned by Edison and Morgan, and made and remade by Welch, Immelt

and 10 other men before him. The moment weighed on the GE veteran

with the enemies' list in his head.

The preparations were intense. Investment bankers, crisis PR

consultants and other advisers were brought in to finish the plan

and help Flannery construct a message he would deliver in a

surprise announcement June 26.

He presented a plan that many expected back in November. GE

would spin off its health-care division, sell its stake in

oil-field supply company Baker Hughes, cut its debt and streamline

its sprawling corporate structure. The stub of GE Capital was all

that remained unresolved.

Almost as an afterthought, it was announced that Larry Culp had

been elevated to lead director, replacing Jack Brennan, the former

CEO of giant mutual-fund company Vanguard Group.

Culp had the kind of successful industrial pedigree that

investors, including Trian, wanted steering the board. Some

directors thought GE should abandon its tradition of having the CEO

also serve as chairman. Having a strong lead director was a good

compromise.

Culp grabbed the reins in the summer board meetings, drilling

the new CEO on questions about the power business, scolding

Flannery in front of directors for not knowing such nitty-gritty

details as inventory levels. Given the sprawl of GE, few expected

Flannery to have them at the ready.

In his previous life at the much smaller Danaher, Culp was known

for immersing himself in its various companies. Rather than

bringing executives to headquarters for reviews, he would travel to

their offices and walk the factory floors.

For some on the board, the dressing down revealed a bigger

problem. Flannery lacked the experience to juggle the steady flow

of crises while also running the company that he was still learning

about. Flannery felt he was bringing scrutiny to major issues, like

how to best spend GE's money, that were previously glossed

over.

But there was also a group on the board who already wanted to

consider pushing Flannery out. They were worried he wasn't up to

the job, and GE had no room for error. Even a normally manageable

problem could mean disaster.

It came from the blades in GE Power's newest line of heavy-duty

gas turbines. They were failing. Exelon, a big utility, was forced

to shut two power plants in Texas for repairs. GE would need to fix

dozens of other turbines it had sold. That promised to damp already

weak sales and drive up maintenance costs in the struggling unit.

GE was counting on that turbine to battle rivals such as

Siemens.

There was more. GE was on pace to miss its cash-flow targets and

would have to take a charge of more than $20 billion to write off

the value of previous acquisitions, including Alstom. Flannery

briefed directors in a conference call on Wednesday, Sept. 26.

By the end of the weekend, Flannery was out, fired after 14

months, the shortest stay at the top in GE's long history. The new

boss was Larry Culp.

Culp hadn't been looking for the job when he joined the board,

and didn't accept it lightly. He had retired three years before and

was spending much of his time working with his alma mater,

Maryland's Washington College, sitting on corporate boards and

working as a senior adviser to Bain Capital, the private-equity

firm.

He saw opportunity, though, and thought he would be a good fit.

After all, he had 14 years of experience as a CEO and was only 55.

Unlike Flannery, he acted decisively, slashing the GE dividend

again within his first weeks on the job, leaving investors to

collect a token 1 cent per share each quarter.

Like Flannery, he still planned to dismantle the company, now

beset by investigations, lawsuits and waning confidence that it

could pay its debts.

Federal criminal and civil investigators were looking into the

ways GE Power had modified service contracts to wring out more

short-term profits. They were probing how GE Capital disclosed its

continuing liability for long-term-care insurance, as well as

write-off Alstom and other deals.

Shareholders accused the company of defrauding them, citing the

power contracts and insurance liability in their lawsuits. GE has

denied the allegations. And GE, once the owner of credit almost as

good as the U.S. government, saw rating agencies drop the grades on

its once-golden bonds.

Like Flannery, when Culp spoke the stock sank. In a fidgety TV

interview in November, he said the power business had yet to hit

bottom. He declined to set new financial targets. GE's stock soon

fell below $7 for the first time since the financial crisis.

The collapse has been so complete that there is little left to

lose. JP Morgan analyst Steve Tusa, who led the pack in arguing

that GE was harboring serious problems, removed his sell rating on

the stock this week. GE's biggest skeptic still thinks the

businesses are broken but the risks are now known. The stock

climbed back above $7 on Thursday, but is down more than 50% for

the year and nearly 90% from its 2000 zenith.

As far and as hard as the fall looked to those on the outside,

it felt even farther and harder to those who had been on the

inside, the true-believers like Jack Welch and Jeff Immelt and John

Flannery, GE men through and through. Today as they try to

reconcile how a company valued at nearly $600 billion 18 years ago

is now worth a tenth of that, they can't help but feel the deep

sting of the slights of history.

Since being forced out, Flannery has kept his distance from GE.

The 56-year-old set out on a six-week road trip with his wife, a

journey he long dreamed of taking but couldn't fit into his three

decades of climbing to the top of General Electric. He was

crisscrossing the American landscape that not long ago he was

cruising above in business jets.

Flannery is unrepentant about refusing to be rushed into

plotting a better course for the company he loved. He had unearthed

serious problems, every decision was heavy, affecting thousands of

factory jobs or a lonely retiree waiting for a dividend check. In

exile, he remains certain that there was no quick fix no matter how

much investors and the board wanted one.

Immelt, now 62, divides his time between Silicon Valley, where

he joined a venture-capital firm and sits on the boards of four of

its startups, and Watertown, Mass., where he serves as chairman of

Athenahealth Inc., a medical-software company. In a sun-filled

office in the rehabilitated brick factories of an old arsenal

complex, Immelt is doing what he told colleagues he wanted to do

after leaving GE: work with young, growing tech companies.

But the anguished way he left the company to which he'd devoted

his life remains fresh. He feels misunderstood and unfairly

portrayed. He has quipped to some in Silicon Valley that he takes

solace in the fact that no one there watches CNBC or reads The Wall

Street Journal.

Immelt sees his tenure as Sisyphean, a battle against gravity as

he tried to break the company free of its dependence on Capital

only to reveal unseen weakness in the power business that was

supposed to be GE's strength.

"The notion of plugging financial services and industrial

companies together, maybe it was a good idea at a point in time,

but it is a uniquely bad idea now," Immelt said this week.

Welch, now 83, has slowed from his relentless peak, but was a

ubiquitous presence on Nantucket this summer, never hiding his

disdain for the man he chose to succeed him. He fumed about

operational failures in the power business, and the execution of

the pivot. Welch readily greeted old acquaintances with a grimace

about the latest news of the company, saying he gave himself an A

for the operation of his old shop, and an F for his choice of

successor.

"I'm terribly disappointed. I expected so much more," he said

this week. "I made the best choice I thought I could make, and it

didn't turn out right."

The old chairman isn't sure the powerhouse of his time can be

revived, but he hopes that Larry Culp can "build a new GE."

To Flannery, Immelt, Welch and the others schooled in

Crotonville, Larry Culp's ascension punctured a deep and abiding

conviction: General Electric made the greatest managers in the

world, who could run anything better than anyone else. When the

company they loved needed them most, though, the heirs to Edison's

ingenuity had run out of ideas.

In the cruelest of codas, the last CEO of America's last great

industrial conglomerate would be an outsider.

--Illustration by Justin Metz | Design by Tyler Paige | Graphics

by Hanna Sender

Write to Thomas Gryta at thomas.gryta@wsj.com and Ted Mann at

ted.mann@wsj.com

Join WSJ journalists in a live subscriber-only call on what

happened at GE, how they got the inside story and what it all

means. Register at wsj.com/gecall, and send your questions on GE to

subscribercall@wsj.com.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

December 15, 2018 02:47 ET (07:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

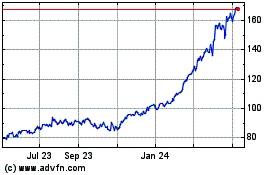

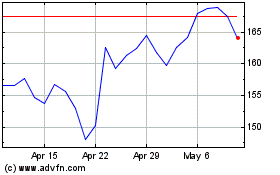

GE Aerospace (NYSE:GE)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

GE Aerospace (NYSE:GE)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024