By Paul Hannon, Timothy W. Martin and Sam Schechner

LONDON -- The U.K. government said it would move ahead with

plans to introduce a new tax targeting revenue generated locally by

large tech firms, setting the country on a path to become the first

developed country to roll out such a "digital" tax.

The new tax is still subject to final rule making and won't

start until 2020. Still, it comes as dozens of other countries are

contemplating new levies on digital services sold by companies such

as Alphabet Inc.'s Google and Facebook Inc. These governments are

hoping to capture more revenue from digital services as economic

activity increasingly shifts online.

The U.K. treasury chief, Philip Hammond, said Monday the tax

would only target large, profitable companies, with global revenues

of at least GBP500 million ($640 million.) The new levy would

target 2% of such a company's revenue in the U.K. Mr. Hammond said

it could eventually raise some GBP400 million annually.

The tax would be levied on activities linked to U.K.-based usage

of services like search engines, social media platforms and online

marketplaces. The tax was one of a series of fiscal measures

disclosed as part of the government's annual budget.

The Office for Budget Responsibility, the U.K.'s fiscal

watchdog, said that the Treasury's estimate of how much tax the new

levy will raise is highly uncertain. Among the questions as yet

unanswered about the new tax's structure are whether it will be

deductible against corporation tax, for instance. The watchdog also

flagged a range of ways the new levy could affect corporate

behavior as companies seek to minimize any liability, such as by

reclassifying revenue as income not covered by the tax.

Still, the OBR said it is also possible the digital-services tax

could prove a bigger money-spinner for the Treasury than its

preliminary estimates suggest, given that online activity accounts

for a growing share of the overall economy.

For giants like Alphabet, Amazon.com Inc. and Facebook, the U.K.

tax would amount to a relatively small sum of additional tax. But

it represents the first concrete step among several governments

globally to increase the tax burden of these and other large,

global tech-services companies.

The effort comes amid a yearslong backlash among governments,

particularly in Europe, against companies that critics say aren't

paying their fair share of taxes.

Opponents of digital taxes, which include lobbyists for

multinationals and countries with large amounts of exports, say a

patchwork of new rules that vary by country will hurt smaller

companies. They say the initiatives could lead to double taxation

of corporate profits, which will stifle international trade and

discourage investment.

The tech industry opposes the proposals. On Monday, after the

U.K. announced its planned tax, the Information Technology Industry

Council, a Washington, D.C.-based lobby group that represents tech

companies including Google and Facebook said that "imposing a

digital tax could create a chilling effect on investment in the

U.K. and hinder businesses of all sizes from creating jobs."

Amazon and Alphabet declined to comment on the new tax. Facebook

and Apple didn't immediately respond to requests for comment. All

four companies have said in the past, amid criticism of their tax

practices, that they pay their fair share.

The U.K. first said it had justification for a new tax in

November 2017, arguing users of digital services help make the

product that tech companies sell to advertisers and other

customers. That principle has influenced the rest of the European

Union, which is working on its own tax proposal.

Since launching a broad effort to overhaul the system for taxing

companies that operate internationally in 2013, developed-country

governments have been divided on whether to introduce new levies

that specifically target digital companies or to treat digitization

of the economy as a process that requires a more broad-based

response. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and

Development, which oversees international tax negotiations, hopes a

compromise can be reached by 2020.

Mr. Hammond said that while a global agreement "is the best

long-term solution," progress has been "painfully slow." The U.K.

said its new tax would only be in force until a global solution is

found, but Mr. Hammond said "we cannot simply talk forever."

Inspired by European Union proposals to impose a tax based on

the revenue of tech companies rather than their profit, South

Korea, India and at least seven other Asian-Pacific countries are

exploring new taxes. Mexico, Chile and other Latin American

countries too are contemplating new taxes aimed at boosting

receipts from foreign tech firms.

Such taxes, which are separate from the corporate income taxes

many companies already pay, are broadly known as digital taxes and

could add billions of dollars to companies' tax bills. They seek to

impose levies on digital services sold by global companies in a

given country from units based outside that country. In some cases,

the proposed taxes target services involving the collection of data

about local residents, such as targeted online advertising.

Europe is the largest overseas market for many tech companies,

and the EU estimates that its proposal would bring in about EUR5

billion ($5.7 billion) annually. But digital taxes could eventually

take a bigger bite in Asia, where growth is faster and there are

many more internet users.

At the heart of the debate is the question of where tech giants

should pay their taxes.

Under international tax principles, income is taxed where value

is created. For tech companies, that isn't always clear. Services

including advertising and taxi reservations are now often delivered

digitally from halfway around the world, by companies that pay

little income tax locally.

U.S. tech companies often report little profit, and therefore

pay little income tax, in the overseas countries where they sell

their digital services. That is because customers in those

countries are actually buying from a unit based elsewhere, often a

low-tax country. The in-country unit is tasked with marketing and

support, and the overseas unit that actually makes sales reimburses

the local unit for expenses, leaving little taxable profit.

Under growing political pressure, some tech companies, including

Amazon.com., Facebook and Google, have recently started declaring

more revenue in countries where they do business. But they also

declare more expenses locally, which could offset much of that

additional revenue.

The U.K. tax and the other global proposals put pressure on

countries with large economies -- including the U.S., which last

year imposed a new minimum tax on U.S. multinationals' overseas

profits -- to arrive at an agreement about how to tax the digital

economy. The OECD has been leading international talks with the

goal of reaching a consensus by 2020.

Pascal Saint-Amans, the head of the group's tax-policy center,

said the proposals create an incentive to move more quickly. "We

understand there has been some frustration, and there is a

political urgency," he said. "We cannot ignore it."

On Thursday, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin expressed concern

over "unilateral and unfair" tax proposals aimed at U.S. tech

companies and urged his overseas counterparts to work within the

OECD on a global plan.

Write to Paul Hannon at paul.hannon@wsj.com, Timothy W. Martin

at timothy.martin@wsj.com and Sam Schechner at

sam.schechner@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

October 29, 2018 15:02 ET (19:02 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

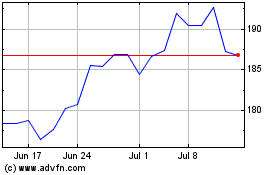

Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOG)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

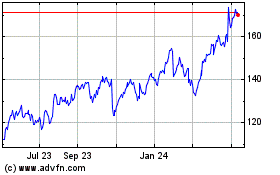

Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOG)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024