By Ben Kesling and Dustin Volz

Kris Goldsmith's campaign to get Facebook Inc. to close fake

accounts targeting U.S. veterans started with a simple search.

He was seeking last year to gauge the popularity of the Facebook

page for his employer, Vietnam Veterans of America. The first

listing was an impostor account called "Vietnam Vets of America"

that had stolen his group's logo and had more than twice as many

followers.

Mr. Goldsmith, a 33-year-old Army veteran, sent Facebook what he

thought was a straightforward request to take down the bogus page.

At first, Facebook told him to try to work it out with the authors

of the fake page, whom he was never able to track down. Then, after

two months, Facebook deleted it.

The experience launched him on a hunt for other suspicious

Facebook pages that target military personnel and veterans by using

patriotic messages and fomenting political divisions. It has become

a full-time job.

Working from offices, coffee shops, and his apartment, he has

cataloged and flagged to Facebook about 100 questionable pages that

have millions of followers. He sits for hours and clicks links,

keeping extensive notes and compiling elaborate spreadsheets on how

pages are interconnected, and tracing them back, when possible, to

roots in Russia, Eastern Europe or the Middle East.

"The more I look, the more patterns I see," he said.

Facebook's response to his work has been tepid, he said. Company

officials initially refused to talk with him, so he used a personal

contact at Facebook to share his findings. Lately, the company has

been more active.

Facebook didn't respond directly to a list of questions about

Mr. Goldsmith's research, but a spokesman said the company had

14,000 people working on security and safety -- double the amount

last year -- and a goal of expanding that team to 20,000 by next

year.

In a statement, the spokesman said the company relied on "a

combination of automated detection systems, as well as reports from

the community, to help identify suspicious activity on the platform

and ensure compliance with our policies."

About two dozen of the pages Mr. Goldsmith flagged, with a

combined following of some 20 million, have been deleted, often

coinciding with Facebook's purges of Russian- and Iranian-linked

disinformation pages -- including a separate crackdown by the

company last week on domestic actors.

The most recent suspensions included the page "Vets Before

Illegals," with nearly 1.4 million followers, which Mr. Goldsmith's

research showed had five page administrators in the U.S. as well as

three in the Philippines and DcGazette, a page pushing conservative

news that had attracted more than 400,000 followers.

Several of the pages Mr. Goldsmith has studied expressly catered

to conservative audiences and frequently promoted divisive memes

depicting President Trump favorably on issues involving veterans,

illegal immigration and the National Football League. While posts

didn't specifically discuss congressional candidates seeking

election in next month's midterms, they often promoted Mr. Trump's

2020 reelection bid while disparaging Hillary Clinton as a criminal

who deserved jail time.

But, based on his own research, he says the company needs to do

much more. "They have a responsibility" to deal with manipulative

accounts, Mr. Goldsmith says. "What you see on Facebook is your

reality."

Mr. Goldsmith is part of a cottage industry of digital

detectives investigating malfeasance on social media that extends

beyond internet firms, journalists and academics to include

ordinary citizens.

"They see me as a novice cybervigilante, and not someone with

the reputation of a research university to back me up," Mr.

Goldsmith said of Facebook. "Which, to be fair, is exactly the

case."

What U.S. intelligence agencies say was a widespread effort by

the Kremlin to influence the 2016 presidential elections -- and

renewed warnings about attempts to influence the midterms -- have

added urgency to their cause.

Facebook has vowed repeatedly to counter disinformation. Chief

Executive Mark Zuckerberg has called the effort an arms race, and

said the company is banking on artificial intelligence to better

detect manipulation campaigns.

The inner workings of Facebook's detection and takedown system

remain opaque, making it hard to evaluate the effectiveness of its

efforts -- even for those like Mr. Goldsmith, who has made it a

mission to track webs of connected pages.

Lee Foster, who manages the internet firm FireEye's information

operations intelligence analysis unit, a misinformation-tracking

team, said his team of investigators often struggles to discern

whether a Facebook page that appears fraudulent is a

foreign-influence campaign, a financially motivated click farm, or

something else.

Mr. Goldsmith's persistence and some help from congressional

aides led to a phone call among him, Facebook and House

Intelligence Committee staffers, and then a meeting at Facebook's

office in Washington, D.C. Facebook has responded to some of his

emails, but hasn't explained why some pages he has identified were

removed while others remain or whether his research contributed to

decisions to suspend certain pages.

The Facebook spokesman said veterans are among those who may be

especially appealing targets to bad actors.

"Financially motivated scams, including romance scams, commonly

rely on impersonating members of the public who are more likely to

be considered trustworthy -- including members of the military,

veterans, and other professionals," the spokesman said. "As a

result, organizations like Vietnam Veterans of America are more

likely to be targets of impersonation than most people on Facebook.

We recognize this and are working to combat impersonation in a

variety of ways."

One of Mr. Goldsmith's top concerns is that bad actors are

determined to try to exploit veteran and law-enforcement

communities. Mr. Goldsmith served more than three years in the

Army, including combat in Iraq.

Researchers have identified veterans as a particular target of

disinformation campaigns. A study from the University of Oxford in

October 2017 found accounts tied to the Kremlin were targeting

veterans and active military personnel on Facebook and Twitter with

divisive political propaganda, likely because of their status as

"influential voters and community leaders."

To Mr. Goldsmith's dismay, he has noticed that even friends and

colleagues follow some of the pages he most distrusts.

One was Maureen Elias, who works on outreach and advocacy at

Vietnam Veterans of America and unwittingly followed and then

shared content from a page Mr. Goldsmith has pegged as bogus. She

said she had followed the page only after seeing her own

acquaintances following it.

"It makes me sick to my stomach to think I've shared content

from these sites that target veterans and don't have our country's

best interests in mind," said Ms. Elias, a 41-year-old Army veteran

who specialized in counterintelligence. "It makes me feel even more

foolish because I fell for this crap. Of all people, I should know

better."

In addition to Facebook, Mr. Goldsmith has contacted at least 10

congressional committees and several federal agencies requesting

help to investigate social media use by foreign actors that target

veterans. The overtures largely were met with silence, though Mr.

Goldsmith said he did hear back from some congressional committee

staffers.

Mr. Goldsmith also has begun to examine suspect Twitter

accounts. A Twitter representative told Mr. Goldsmith this month it

had removed one account he had tracked, due to inactivity.

The representative declined to share information with Mr.

Goldsmith about the origin of the account, but Twitter said to Mr.

Goldsmith that his findings were promising and the company was

interested in learning more. Twitter declined to comment.

After his initial discovery of the fake Vietnam veterans account

on Facebook in August 2017, Mr. Goldsmith began noticing other

Facebook pages that had no original content, that appealed to

veterans, and that shared divisive memes, like one about

African-Americans vandalizing veteran memorials. He logged examples

of multiple pages sharing the same image and message -- minutes

apart.

Some accounts have changed their names over time, testing what

approaches garnered the most "likes" and follows. One he identified

was named "Support Police Officer." It has more than 20,000

followers and posts American military and law-enforcement

memes.

Using a Facebook feature that shows the history of a page's

names, Mr. Goldsmith found that the page began in 2015 as "Europe,

Balkan - Military Power" before changing to "Police & Military"

and then "Support Police" before settling on its current name.

Another page, called "Nam Vets," links to a website whose domain

is registered to a user in Plovdiv, Bulgaria, according to publicly

available data.

Facebook in early September launched a new feature allowing

users to see the country of origin for many, but not all, pages.

Using this tool, Mr. Goldsmith found that of more than 100

suspicious, veteran-focused pages he had been following, over half

had begun in a foreign country, and many in Vietnam, targeting

Vietnam veterans.

"I've identified dozens of these pages, but it's already too

late," Mr. Goldsmith said. "They're not just targeting the midterm

election, they're targeting the electorate."

Write to Ben Kesling at benjamin.kesling@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

October 17, 2018 06:01 ET (10:01 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

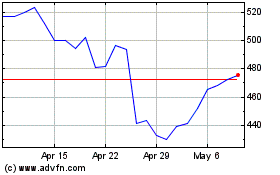

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024