By Paul Ziobro

Union Pacific Corp. never hired Hunter Harrison to run its

sprawling network. But with congestion clogging its system, the

company is now adopting the late railroad maverick's strategy to

speed its freight trains.

The railroad, which until recently had been adding locomotives

and crew, plans to use less equipment in a bid to improve its

financial performance and service.

"By a number of measures, it's evident that we have not made the

kind of progress in improving our service and productivity

performance in recent months," Union Pacific Chief Executive Lance

Fritz said Wednesday.

Union Pacific will shift its focus from moving trains to moving

the individual railcars, with the end goal of providing a tighter

delivery window for customers. It also will try to minimize

downtime for railcars, reduce the number of times cars are sorted

at facilities so-called hump yards and blend different types of

cargo on one train.

The strategy being implemented at Union Pacific was espoused by

Mr. Harrison, who was running rival CSX Corp. when he died last

December. He honed the so-called precision scheduled railroading

model over a five-decade career that included turning around two

large Canadian railroads before he took the helm of Jacksonville,

Fla.-based CSX last year.

During a nine-month stint at CSX where he battled undisclosed

health issues, Mr. Harrison quickly idled hundreds of locomotives,

eliminated thousands of jobs, closed facilities and overhauled

train schedules.

Mr. Harrison's plan was disruptive at each stop, resulting in

thousands of layoffs and jolting changes to railroad schedules that

led to complaints from shippers. But the strategy drastically cut

costs, resulted in faster train times and lifted stock prices.

Union Pacific executives hope the changes will ease congestion

that has lingered on the 32,000-mile railroad for nearly a

year.

As executives detailed the plan Wednesday, they said that they

haven't decided to close any rail yards yet and that specifics on

idling locomotives, laying off workers and other changes typically

associated with Mr. Harrison's strategy haven't been finalized. But

as the plan is rolled out with more precise train schedules, the

company expects costs to drop, and to avoid some of the service

hiccups of the past.

"There are periods when we have fantastic service product and

then periods where that fades," Mr. Fritz said.

The plan will start to unfold next month along the Union Pacific

corridor between Wisconsin and Texas, and be put in place across

the network by 2020.

Union Pacific has been working closely with customers to

communicate the changes, although the revamped operations may

result in some shippers being dropped. "There may be some customers

where we may have to decide that it does not fit in the network,"

said Kenny Rocker, Union Pacific's head of marketing and sales.

Executives have long said that Union Pacific would borrow ideas

from other railroads to improve its performance. In the lead-up to

the plan, the company has tested some precision-scheduled

railroading concepts on parts of its network. Some executives

recently adopted an informal name for weekly meetings aimed at

helping trains run more smoothly: "WWHHD," or "What would Hunter

Harrison do?," two people familiar with the matter said.

Union Pacific's service problems have stemmed from a number of

issues. New technology called positive train control that is meant

to prevent accidents has caused slowdowns, including inadvertent

stops, as it has been rolled out.

The strength in the economy has pushed additional volume onto

Union Pacific's rails, especially in the Southern region of a

network that spans the Western two-thirds of the U.S. Crew

shortages exacerbated the issues. Union Pacific has responded by

bringing locomotives out of storage, adding railcars to handle the

additional cargo and enticing new hires with bonuses of $25,000 or

more.

The network is still facing gridlock. In its second quarter,

Union Pacific's average train speed was 3% slower than a year

earlier, while average time spent at terminals rose 4%. The company

has spent tens of millions of dollars on extra equipment, labor

hours and fuel to unclog the network.

The problems have pushed up Union Pacific's operating ratio to

64% in the second quarter from 61.9% a year earlier. An operating

ratio represents the percentage of revenue consumed by operating

costs, so a decline is an improvement. Investors have demanded

more.

The Omaha, Neb.-based company has faced questions from analysts

as to whether it should follow CSX's strategy to operate with fewer

workers and equipment. It has already made changes, including a

shake-up of its management team last month that included the

retirement of its chief operating officer and the addition of a

chief strategy officer.

The company said the changes being implemented will help its

operating ratio hit 60% by 2020 and 55% longer-term.

Analysts wondered if Union Pacific would need outside help to

implement the changes, or if there is someone capable of

overhauling the company's operations and culture. "That's going to

be critical in order to implement this," Credit Suisse analyst

Allison Landry said.

The railroad isn't currently planning to tap outside help from

other railroads that have undergone a transformation. Mr. Fritz

said that while this is the first time Union Pacific is

implementing Mr. Harrison's principles on a large scale, "they are

not a mystery."

Write to Paul Ziobro at Paul.Ziobro@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

September 19, 2018 10:34 ET (14:34 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

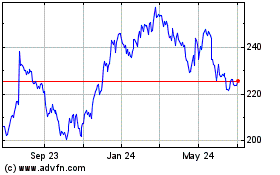

Union Pacific (NYSE:UNP)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

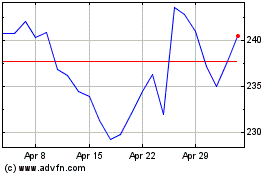

Union Pacific (NYSE:UNP)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024