By Theo Francis

If the U.S. imposes sweeping tariffs on imports from China early

next month as planned, the levies will be felt not only in ports

ringing the Pacific, but also across companies, product lines and

factory towns in the U.S.

For General Electric Co., that includes its business making

magnetic resonance imaging machines, or MRIs, many of which are

assembled at plants in Florence, S.C., and Waukesha, Wisc.

GE, which is struggling to boost profits and revamp its

operations after a series of missteps, has argued to federal policy

makers that it is counterproductive to impose tariffs on components

the company imports from its own plants in China, including some

assembled using parts that were originally made in the U.S.

"Putting tariffs on the parts they produce will not hurt Chinese

businesses or sway Chinese decision makers," GE executive Karan

Bhatia said in a May hearing held by a committee of the Office of

U.S. Trade Representative. "Rather, they hurt U.S. companies that

own these facilities, as well as the U.S. workers and suppliers who

rely on these parts from China to make world-class products in the

United States."

GE's MRI business is just one part of the company's health-care

division, which last year accounted for about 16% of companywide

sales, or $19 billion. Still, it offers a window into the complex

interconnections of global trade, where components made in one

country get assembled in another -- and, once in finished form, may

be sold back into the first. Some parts make more than a single

roundtrip.

"Global supply chains have become so integrated over the last

few decades that it's really hard to put tariffs in place that are

not going to harm some domestic manufacturers," said William Hauk,

an economics professor at the University of South Carolina.

The administration has said tariffs are needed to prevent China

from dominating key industries with unfair state subsidies. A

senior administration trade official said a forthcoming

product-by-product exemption process will seek to take into account

the kinds of scenarios raised by GE, without creating so many

exceptions that it weakens the tariffs' impact.

"We are being as sensitive as we can to these types of problems,

given the overall problem that we're trying solve," the official

said. Still, he acknowledged, some U.S. companies could see costs

rise.

GE, which makes everything from LED bulbs to jumbo jet engines,

has said it expected to be affected by levies imposed on about

three-quarters of an initial list of products facing U.S. tariffs.

But it considers some three dozen products to be critical, in part

because obtaining them elsewhere will prove difficult or require

months to arrange.

That shorter list includes parts for aircraft-engine turbines,

submersible electric pumps, locomotives and steam boilers. It also

includes key parts for X-ray machines and other equipment made by

GE Healthcare -- including MRIs.

GE sells its U.S.-made MRIs for anywhere from $500,000 to $10

million depending on service and other options, analysts say.

Nearly $1 of every $5 in circuit boards and other components for

the scanners is imported from China, the company said.

Some analysts expect the ultimate impact of the China tariffs on

GE to be muted. Chinese imports make up only part of the

manufacturing cost, and end-users will likely be reluctant to

switch brands of complex machinery for a relatively small savings,

said Nicholas Heymann, an analyst for William Blair & Co.

Moreover, competitors, who also manufacture in the U.S., face the

same tariffs.

All told, GE Healthcare's MRI business directly employs about

950 people in the U.S., the company said, plus more who spend at

least part of their time on the products, such as by selling or

servicing multiple products.

At GE's Florence location, workers make the giant magnets at the

heart of the MRI scanners -- each magnet can weigh as much as 9

tons -- and assemble the "cabinet," which contains electronics and

much of the rest of what makes the scanners work. Workers in

Waukesha, a town that is home to about 72,000 people, also assemble

MRI cabinets.

Florence's mayor, Stephen Wukela, said GE has employed people

for decades in the 38,000-person town and is an important part of

an expanding economy that also boasts a paper mill and an Otis

Elevator plant. The region is already feeling the pinch from rising

construction costs, exacerbated by separate U.S. tariffs on steel,

aluminum and lumber.

"If tariffs spread into more products, then there's more

anxiety," said Mr. Wukela, who has run as a Democrat.

In Wisconsin, makers of industrial equipment and parts are also

seeing costs rise with tariffs on Canadian steel, aluminum and

lumber, said Noah Williams, director of the University of

Wisconsin's Center for Research on the Wisconsin Economy.

Still, he added, "the economy is doing relatively well -- this

is a shock, nobody likes it, but they feel like they can absorb it

for now."

Like other companies, GE isn't simply waiting for tariffs to

drive up prices. Mr. Bhatia, GE's president for government affairs

and a former U.S. trade official, has pushed for broad exceptions

for certain imports from China, including those made at

U.S.-controlled factories and those with a significant proportion

of U.S.-made components. The company plans to seek exemptions for

specific products where possible.

The company also is exploring how it could revamp its supply

chain to produce more of the components elsewhere in the world. But

that can't happen quickly, Mr. Bhatia has said. Stringent U.S.

quality and safety rules for medical equipment mean new factories

can take a year or more to bring on line.

The stakes are higher for companies like GE that own the

factories producing their imported parts, said Gary Hufbauer, a

senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International

Economics, a Washington, D.C., think tank. In addition to operating

costs for ramping up production in a new location, they may also

have to try to sell or repurpose their specialized factories in

China.

"The factory may become economically obsolete even though it's

technically very good," Mr. Hufbauer said.

In the meantime, GE could find it tough to pass the cost of the

tariff on to the buyers of its MRI scanners. Three-quarters of GE

Healthcare's medical equipment is sold within the U.S., much of it

to hospitals and other buyers facing tight spending constraints.

The rest is exported to markets, including in China, where

competitors aren't troubled by the U.S. tariffs. Alternatively, GE,

like other industrial companies, could absorb the tariffs, reducing

profit margins in the process.

"Either consumers bear more cost, or we bear the cost and it

ultimately flows down to investment expenditures," Mr. Bhatia said

in an interview. "Either way, you're talking about bad things

happening, ultimately, to the economy."

Write to Theo Francis at theo.francis@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

June 24, 2018 10:10 ET (14:10 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

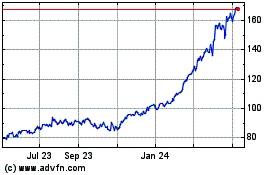

GE Aerospace (NYSE:GE)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

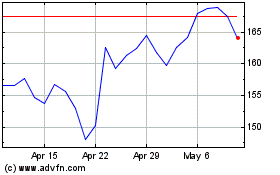

GE Aerospace (NYSE:GE)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024