By Liz Hoffman and Peter Rudegeair

When Spotify Technology SA went public in April, Goldman Sachs

Group Inc. was sitting on a stake in the music-streaming startup

worth more than $350 million, a sevenfold return on a 2012

investment.

Those gains weren't the handiwork of any of the hundreds of

Goldman professionals whose day jobs are to invest in companies.

They came instead from the firm's bankers, who have been quietly

moonlighting as venture capitalists.

These corporate consiglieres, who advise on mergers and

underwrite securities, oversee a venture-capital portfolio worth

several hundred million dollars, according to people familiar with

the matter.

Plenty of big banks invest in promising startups, but they

typically do so through their strategy groups or asset-management

arms. Goldman has those, too, but they are distinct from the

portfolio maintained by its investment bankers, who are investing

on the bank's behalf.

The bankers were early backers of now-household names including

Uber Technologies Inc., online storage vault Dropbox Inc. and

payments company Square Inc. Recent investments, according to the

people, include Ripple Foods Inc., which makes milk from peas, and

Beyond Meat, which makes, as its name implies, meatless

burgers.

As startup valuations have soared, seemingly everyone wants to

be a venture capitalist. Celebrities including Kobe Bryant and

Jared Leto have invested in private companies. A member of the

Dutch royal family cashed in a stake in payments firm Adyen NV when

it went public last week.

Goldman's investment bankers are hoping to cement their ties to

emerging companies that might later hire the bank for an IPO or

sale. (The bank calls it "relationship equity.")

"We are proud to provide creative solutions, excellent execution

and in certain unique situations, small, passive capital

investments to further our client's goals," Dan Dees, Goldman's top

technology banker, said in a statement.

The upside -- if it can pick winners and avoid duds -- is

profits that can far outstrip the fees Goldman might get from those

deals. Goldman made about $15 million advising Spotify on its IPO,

people familiar with the matter said, versus hundreds of millions

of dollars in paper gains on its shares.

The strategy is a throwback to the old merchant-banking

playbook, when banks regularly put capital to work alongside

clients. That model has largely fallen out of favor with large

banks -- a retreat hastened by the crisis and new regulations that

followed -- but is still practiced by a handful of smaller boutique

banks, including Byron Trott's BDT Capital Partners LLC and Skip

McGee's Intrepid Financial Partners LLC.

Goldman's dual roles could pose conflicts as its bankers advise

startups on deals that could result in big profits or losses on the

stakes owned by the investment bank. What's more, Goldman has

raised billions of dollars from outside investors for its

private-equity funds and risks being accused of cherry-picking the

best deals for itself.

Sarah Friar, Square's chief financial officer and a former

Goldman research analyst, said the bank's investment in Square

"showed they wanted to build a relationship more long-term in

nature."

As for the potential conflicts, she said Square does much of its

deal work internally, without hiring bankers, and is "not short of

advice" from other sources.

Still, venture investing is risky, especially now as the

exuberance that propelled valuations sky-high shows signs of

cooling.

Viddy Inc., a startup touted as "the Instagram for video,"

raised money from Goldman in 2012 but shut down its smartphone app

two years later. Investments in ZocDoc Inc., an online appointment

and ratings system for doctors, and e-commerce firm Beachmint Inc.

haven't performed as expected, people familiar with the matter

said.

And Goldman has been burned before. In 1999, the firm invested

$100 million in online grocer Webvan Group Inc., a deal endorsed by

Hank Paulson, who had been a senior investment banker and later

became Goldman's chief executive, people familiar with the matter

said. Webvan went bankrupt two years later as the dot-com bubble

burst.

The recent effort traces back to the lean years after the

financial crisis, when IPOs dried up. Eager to stay close to

promising startups, Goldman focused on introducing them to venture

capitalists. As its bankers brokered fundraising rounds, they began

putting the firm's money in, too.

They invested $25 million in Dropbox in 2011 and $5 million in

Square in 2012, according to securities filings and people familiar

with the matter. Goldman later made loans to both companies and was

lead underwriter on their IPOs.

When Square went public in 2015, its lower-than-expected IPO

price triggered a provision in Square's shareholder agreements that

required the company to give its investors, including Goldman,

additional shares. Goldman was among the banks that helped set the

IPO price.

Goldman invested in Uber at a roughly $200 million valuation in

2011, the people said. The deal -- a huge winner, as Uber's

valuation has soared past $50 billion -- benefited from a stroke of

luck: When Goldman executives sought approval from then-CFO David

Viniar, he had recently received a call from his daughter in San

Francisco about a hot new app that summoned cars on demand.

Goldman's bankers have been branching out in their investing.

What was once known internally as the Internet Fund is now the

Growth Investment Fund, and executives have been tasked with

sourcing investment opportunities in consumer products, financial

services, energy and health care. Recent investments include Beyond

Meats and Ripple, as well as credit-card startup Marqeta Inc., said

people familiar with the matter.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

June 17, 2018 07:14 ET (11:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

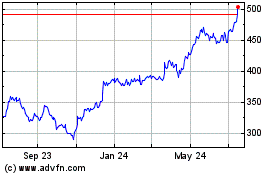

Goldman Sachs (NYSE:GS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

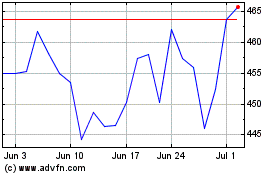

Goldman Sachs (NYSE:GS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024