By Jay Greene and Laura Stevens

It is with a certain dread every autumn that some companies

described by Amazon.com Inc. as its technology partners gather at a

Las Vegas convention and find out if Andy Jassy has new plans to

encroach on their turf.

These firms run their software on Amazon's vast array of servers

-- part of what is known as "the cloud" -- and from there sell use

of their programs to others. Over nearly three hours, the boss of

the Amazon Web Services unit walks the stage, revealing a road map

of brand-new features Amazon itself plans to offer, a few of which

inevitably compete with partners.

Last November, Emil Eifrem, one of roughly 100,000 people

watching Mr. Jassy's keynote in the hall or remotely, braced for

what he expected to be one of the announcements, a data-graphing

service. Mr. Eifrem's company, Neo4j Inc., says it defined the

technology, which allows customers to analyze data on Amazon's

platform and others. Two years ago, as it researched the market,

Amazon visited Neo4j asking for help building a similar product,

said Mr. Eifrem, Neo4j's chief executive. Neo4j declined.

Mr. Jassy did announce Amazon's competing service in Las Vegas

and made it widely available this week. "When Amazon launches in

your space, you're stupid if you don't get scared by that," Mr.

Eifrem said, "because they do tend to outcompete everyone."

Amazon's web-services business has been blazingly successful,

and a look at how that came to be stands as a master class in how

Amazon wins -- and why now it has become a political target. The

unit has become the Seattle company's cash cow, providing 73% of

its operating income, or $1.4 billion, on about 11% of its $51

billion in total revenue it reported in the most recent

quarter.

Mr. Jassy made $194,447 last year, the second most among

Amazon's top officers after CEO Jeff Bezos, who made $1.7 million.

In 2016, Mr. Jassy received shares that were then valued at $35.4

million, in addition to his salary -- the most any top Amazon

executive received that year.

A web-services platform such as Amazon's lets businesses and

other entities rent computing resources at giant server farms,

allowing them to do computing tasks in the so-called cloud rather

than buying their own servers and software. Amazon was early to

build such a platform, and in doing so it upended the

information-technology industry, pressuring incumbents that sold

hardware and software.

Mr. Jassy's strategy echoes one Amazon employed in retail.

There, it built a dominant platform and became a powerful ally to

brands and vendors of goods sold on its website. Then Amazon also

began selling its own brands and goods that competed with some of

its vendors.

In its cloud services, Mr. Jassy built a platform that can weave

a multitude of programs in a seamless web of offerings, its own as

well as partners'. And Amazon then began selling its own services

that compete with some.

"On top of everyone's mind is this black-widow behavior," said

Bill Richter, chief of Qumulo Inc., a Seattle startup that offers

data storage and management on Amazon's system. Amazon doesn't

compete with his company, but every year, he said, "we pray there's

not some big announcement" of an Amazon service that will.

There is growing concern in Washington and abroad about the

dominance of giant tech firms such as Alphabet Inc.'s Google and

Facebook Inc. Amazon, too, has come under attack from right and

left. President Donald Trump in March tweeted that it is "putting

many thousands of retailers out of business!" Sen. Bernie Sanders

in an April Facebook post raised concerns about Amazon's

"extraordinary power and influence."

Mr. Bezos, at Amazon's annual meeting Wednesday, answered a

question about the mounting criticism, saying all large

institutions "deserve to be inspected and scrutinized. It's

normal."

Much of the ire focuses on Amazon's retail heft, but the story

of Amazon's web services helps show how far the company is

spreading its tentacles, with huge success. Mr. Jassy has turned

the world's largest online retailer into a dominant source of

corporate technology online.

Amazon is market leader, reporting $17.5 billion in web-services

sales last year. No. 2 Microsoft Corp. had $5.3 billion in revenue

last year from its cloud-infrastructure business, estimates

investment firm Stifel Nicolaus & Co.

The rising concern is over how Amazon's dominance may give it an

advantage in new businesses. None of the Amazon partners The Wall

Street Journal spoke with would say publicly that new Amazon

competition damaged its business. Privately, some said they worry

Amazon's encroachment may do damage eventually.

One reason there is angst but no visible pain when Amazon

suddenly competes is that there is plenty of business to go around,

said Tod Nielsen, CEO of a cloud-application company named

FinancialForce.com Inc. "The total addressable market is so big.

We're really in the early days of the land grab."

Mr. Jassy said in a November interview that Amazon is providing

services that customers are asking for. "You'll continue to see us

add services as customers tell us they make sense and they want

them from us." He declined this week to comment further. In a 2016

interview, he said: "In every one of the spaces where we have built

further up the stack, our ecosystem partners who've built

significant offerings on top of our platform have done just fine.

These are gigantic markets."

Antitrust questions

Amazon's position raises the kind of concerns seen years ago

over practices of companies such as Microsoft. That company's use

of its dominance in personal-computer operating systems to move

into others' turf lay at the center of the landmark antitrust case

against it.

Microsoft and the federal government settled in 2001, with

Microsoft agreeing to such business restrictions as not engaging in

some discriminatory practices. At the time, Microsoft founder Bill

Gates called the deal "a good compromise and good settlement."

Amazon could run afoul of antitrust law if it tied new services

to its cloud-infrastructure offering, making it less likely

customers would use rival products, said Herbert Hovenkamp, a

University of Pennsylvania Law School antitrust professor. Moves by

Amazon to require customers and partners to use its services,

rather than competitors', would also get regulatory scrutiny, he

said.

One difference is Amazon Web Services isn't as dominant as

Microsoft's Windows in the late 1990s, when Microsoft held more

than a 90% share of its market. Goldman Sachs & Co. pegged

Amazon's share of the so-called public-cloud market at 42% last

year.

Amazon views the market more broadly, including all corporate

tech spending in the cloud and in companies' own data centers. By

that measure, Amazon's share "represents a single digit

percentage," said an Amazon spokeswoman. Amazon Web Services, she

said, "competes with the largest and most successful technology

companies in the world in a market segment that's trillions of

dollars in size."

And Amazon isn't growing as quickly as Microsoft and Google in

cloud computing. Microsoft's revenue from the business gained 94%

and No. 3 Google's more than doubled in the most recent quarter,

while Amazon's climbed 45%, according to Goldman Sachs.

Some partners praised what they said is Mr. Jassy's ability to

straddle the line between ally and rival, including CEO Bob Muglia

of Snowflake Computing Inc., a data-warehousing service. It

competes with an Amazon offering that existed when Snowflake began

offering it on the platform. Mr. Muglia, speaking of his earlier

days running Microsoft's division that worked with developers and

corporate customers, said: "Andy has done a better job partnering

with companies he competes with than I did."

The data weapon

One Amazon weapon is data. In retail, Amazon gathered consumer

data to learn what sold well, which helped it create its own

branded goods while making tailored sales pitches with its familiar

"you may also like" offer. Data helped Amazon know where to start

its own delivery services to cut costs, an alternative to using

United Parcel Service Inc. and FedEx Corp.

"In many ways, Amazon is nothing except a data company," said

James Thomson, a former Amazon manager who advises brands that work

with the company. "And they use that data to inform all the

decisions they make."

In web services, data across the broader platform, along with

customer requests, inform the company's decisions to move into new

businesses, said former Amazon executives.

That gives Amazon a valuable window into changes in how

corporations in the 21st century are using cloud computing to

replace their own data centers. Today's corporations frequently

want a one-stop shop for services rather than trying to stitch them

together. A food-services firm, say, might want to better track

data it collects from its restaurants, so it would rent computing

space from Amazon and use a data service offered by a software

company on Amazon's platform to better analyze what customers

order. A small business might use an Amazon partner's online

services for password and sign-on functions, along with other

business-management programs.

Amazon said it doesn't peer into the sensitive data such as

customer records, corporate accounts and other data that its

business partners store on Amazon's servers.

Amazon engineers are adding features and services at a rapid

pace, more than 1,400 last year. "They never let up on the gas

pedal," Mr. Bezos told shareholders Wednesday. "Our customers are

loyal to us right up until the second a competitor offers a better

service."

The day before his November 2017 keynote, Mr. Jassy previewed

his speech with venture-capital firms in a windowless Las Vegas

conference room, two attendees said. One venture capitalist asked

Mr. Jassy if he planned to launch services that could threaten

startups that built their businesses on Amazon's platform. Mr.

Jassy replied, they said, that any time Amazon moved into a market

niche, companies already there continued to succeed because the

markets are large and growing.

The notion that Amazon's entry in a market won't hurt new rivals

"doesn't quite pass the smell test," said one of the attendees, a

venture capitalist who said he worries about the threat to

companies in his portfolio.

"A lot of CEOs go into Andy's keynote saying, 'God, I hope

Amazon doesn't introduce a product that competes with mine,' " said

Snowflake's Mr. Muglia.

The introductions continue after Las Vegas. In December, Amazon

launched Single Sign-On, which manages access to Amazon Web

Services accounts, a move some believe will put it in competition

with Okta Inc., which offers a way for customers to sign on once

across multiple services. Okta CEO Todd McKinnon said his company's

product lets users sign in across a broader array of companies than

Amazon's. Still, "we're paranoid," he said, "so we're watching

them."

Inside job

Mr. Jassy is a 20-year insider, a Harvard M.B.A. who led Amazon

into music CDs and did a gig in the early 2000s shadowing Mr. Bezos

as his technical assistant. He has led Amazon Web Services, known

as AWS, since 2003.

The idea for the service, he said, was discussed at a 2003

brainstorming session in Mr. Bezos' living room. Participants began

looking into how Amazon, which had built data centers to manage its

retail operation, could turn that expertise into a business.

Early on, AWS focused on being a place where companies could

build code and store data, and from which they could offer services

to firms wanting to do business tasks in the cloud. The vision was

that "any individual in his or her own garage or dorm room," Mr.

Jassy said, "could have access to the same cost structure and

scalability and infrastructure as the largest companies in the

world."

"We thought we would have database services," he said, "but we

didn't anticipate building our own."

AWS appealed to startups, which, with just a credit card, could

buy the computing services they needed. Airbnb Inc., Lyft Inc. and

Pinterest Inc. are AWS customers. More-established corporations

came along later.

Initially, Amazon built a few massive data centers in the U.S.

It now has 55 collections of data centers globally.

Amazon's partners saw it becoming a rival in 2015, when Mr.

Jassy introduced a data-analytics tool, QuickSight, in his keynote.

That encroached on partners such as Tableau Software Inc.

QuickSight has gained some traction with small and midsize

businesses, while Tableau has had success with larger corporations,

said Stifel Nicolaus analyst Tom Roderick. The threat looms, he

said, that Amazon will pluck off those bigger customers. "The fact

is that Amazon is the bogeyman that can come at you in three to

five years."

Tableau CEO Adam Selipsky, a former AWS executive and a friend

of Mr. Jassy's, said: "There are tiny areas where the companies are

in competition, but it's really noise."

Companies happy with Amazon's web services despite competing

with Amazon include Netflix Inc., whose CEO, Reed Hastings, said

Mr. Jassy took a hands-on approach to securing his business.

"As Andy would say, we are particularly valuable because we

competed," said Mr. Hastings, saying he isn't concerned about

Amazon's move a few years ago to become a rival in video.

Amazon's decisions to move into others' markets are part of

doing business, said Barry Crist, CEO of Chef Software Inc., which

makes tools to automate developer tasks and has limited competition

with Amazon in the business of provisioning computing

resources.

"As a small company, you've got to be the minnow that swims in

and out of the mouth of sharks," he said. "If you get lazy, that

mouth might close on you."

Write to Jay Greene at Jay.Greene@wsj.com and Laura Stevens at

laura.stevens@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

June 01, 2018 05:44 ET (09:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

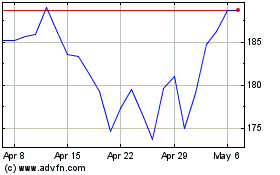

Amazon.com (NASDAQ:AMZN)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Amazon.com (NASDAQ:AMZN)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024