By Daniel Kruger and Akane Otani

The yield on the 10-year U.S. Treasury note hit 3% for the first

time since 2014 in a vote of confidence for the economic expansion,

but warnings from large companies that profits were peaking helped

send the Dow industrials to their fifth straight decline.

Investors on Tuesday dealt with two conflicting messages. The

rise in bond yields early in the day was a signal that the Federal

Reserve might have to raise interest rates more rapidly to respond

to economic growth and the prospect of more inflation. That could

add fuel to the long stock rally.

Yet a handful of large companies sounded a different tune: It

might not get much better than it is now.

That sent both stocks and bonds down, the latest move in a wave

of volatility after a banner year in which nearly all assets seemed

to be constantly charging higher. The Dow Jones Industrial Average

tumbled 424.56 to 24024.13, leaving it 9.7% below its Jan. 26

record close.

Shares of heavy-machinery manufacturer Caterpillar Inc. --

considered a bellwether for industrial America -- tumbled 6.2%

after company officials cautioned first-quarter results could mark

a "high-water mark for the year," while multinational conglomerate

3M Co. shed 6.8% after the company trimmed the top end of its

fiscal-year earnings guidance.

"If you've got production costs going up and interest costs

going up, you're saying, wait a minute -- is this as good as it's

going to get?" said Michael Farr, president of Farr, Miller &

Washington, a money-management firm.

Bond yields had slumped near historic lows in the postcrisis

years as economic growth contracted and the Federal Reserve

undertook bond buying on a massive scale. A rise to 3% signifies in

part that the economy is returning to near normal conditions in

which a rapid deceleration is deemed less likely than it was in the

years immediately after the crisis.

Yet many analysts believe the U.S. is in the late stages of the

economic cycle, and say a rapid run-up in bond yields could pose a

threat to the stock rally, with rising inflation rates discouraging

consumer spending and increasing labor costs.

The yield on the benchmark 10-year U.S. Treasury note, a

barometer that influences borrowing costs for consumers,

corporations and state and local governments, rose as high as

3.001% Tuesday -- its highest intraday level since Jan. 9, 2014 --

before settling at 2.983%, up from 2.973% Monday. Yields rise as

bond prices fall.

The 10-year yield's half-percentage point climb to similar

heights earlier this year contributed to the tumble that sent

stocks into correction territory in February, as higher yields

dented investors' confidence that stock valuations could rise

unceasingly.

Stocks had appeared to stabilize in the months following the

selloff, with the S&P 500 reclaiming positive territory for the

year after a 10% fall from its Jan. 26 high. Yet the stock market's

lackluster response to earnings reports Monday and Tuesday,

combined with the fresh rise in bond yields, has renewed investor

fears of a resurgence in selling.

"The repricing of interest rates is potentially a bigger

headwind for financial markets than the real economy," said Ashok

Bhatia, a senior portfolio manager in Neuberger Berman's Fixed

Income Multi-Sector Group.

Not all are convinced that bond yields will continue their march

higher. The 10-year yield has topped 3% several times since the

financial crisis, only to soon retreat below the level. That

pattern has left investors debating whether this latest surge marks

a new phase in the recovery or the latest in a series of false

starts.

"We are a buyer of 10-year Treasurys" versus riskier assets,

said James Camp, managing director for fixed-income at Eagle Asset

Management. He said investors who prize dividend income may begin

to find bonds at higher yields more attractive.

Still, many believe long-nascent inflation could finally be

picking up, something that they expect will ultimately nudge bond

yields higher.

U.S. crude is approaching $70 a barrel for the first time since

2014, while tighter trade policies, including tariffs on steel and

aluminum imports, are threatening to drive prices across the

economy higher. Inflation poses a threat to the value of government

bonds because it chips away at the purchasing power of their fixed

payments and can push the Fed to raise interest rates.

Further increases in interest rates could pressure stocks, which

for years had benefited from anemic bond yields that made their

returns look relatively attractive.

"For a long time, stocks were essentially the only game in

town," said Jack Ablin, chief investment officer at Cresset Wealth

Advisors. "As interest rates become more competitive, that's going

to put more pressure on equities."

Others see a warning sign in the narrowing distance between

short- and longer-term bond yields, known as a flattening yield

curve. Two-year yields -- which fell to 2.466% on Tuesday -- tend

to rise along with investors' expectations for tighter Fed policy,

while longer-term yields are more responsive to the outlook for

growth and inflation.

Because short-term rates have exceeded longer-term rates before

each recession since at least 1975 -- a phenomenon known as an

inverted yield curve -- investors become wary as the curve

flattens.

The pace of flattening suggests the yield curve could invert in

early 2019, with a recession following a little more than a year

after, said Adrian Helfert, deputy head of global aggregate

investing at Amundi Pioneer.

Yet the flattening has occurred while economic growth continues

to be steady, and few analysts see signs of any imminent

slowdown.

While investors debate the meaning of the flattening curve, one

factor that could propel yields higher is increased government

borrowing. This year's rise in yields came after the passage of

$1.5 trillion in tax cuts and the bigger bond sales the government

needs to finance them. The Congressional Budget Office forecasts

that the deficit will top $1 trillion in 2020 and remain above that

level for the foreseeable future.

Yet other factors could cap the climb in bond yields. Because

the 10-year yield is a benchmark rate used to help set interest

rates for different kinds of loans, including mortgages, auto loans

and corporate debt, higher yields increase the cost of debt, which

can act as a brake on the economy. Yields remain low by historical

standards and the implied inflation forecast from inflation-indexed

Treasurys recently hit a 2018 high of 2.19% for the next 10

years.

While the financial crisis happened almost 10 years ago, the

long path to 3% shows that the pain is only "slowly wearing off,"

said Jeremy Siegel, professor of finance at the University of

Pennsylvania's Wharton School.

Write to Daniel Kruger at Daniel.Kruger@wsj.com and Akane Otani

at akane.otani@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

April 24, 2018 20:11 ET (00:11 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

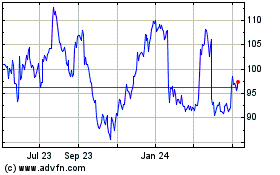

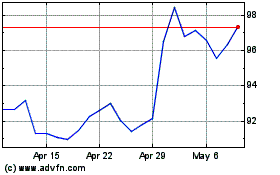

3M (NYSE:MMM)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

3M (NYSE:MMM)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024