By Sam Schechner and Nick Kostov

When the European Union's justice commissioner traveled to

California to meet with Google and Facebook last fall, she was

expecting to get an earful from executives worried about the

Continent's sweeping new privacy law.

Instead, she realized they already had the situation under

control. "They were more relaxed, and I became more nervous," said

the EU official, V ra Jourová. "They have the money, an army of

lawyers, an army of technicians and so on."

Brussels wants its new General Data Protection Regulation, or

GDPR, to stop tech giants and their partners from pressuring

consumers to relinquish control of their data in exchange for

services. The EU would like to set an example for legislation

around the world. But some of the restrictions are having an

unintended consequence: reinforcing the duopoly of Facebook Inc.

and Alphabet Inc.'s Google.

On May 25, the EU will begin enforcing the new rules, which in

many cases require companies to obtain affirmative consent to use

European residents' personal information. The change has sent

shudders through the digital-advertising sector, from online

publishers to the analytics firms, data brokers and buying

platforms that use personal data to aim ads at individuals in real

time.

Google and Facebook, however, are leveraging their vast scale

and sophistication as they seek consent from the hundreds of

millions of European users who visit their services each day. They

are applying a relatively strict interpretation of the new law,

competitors say -- setting an industry standard that is hard for

smaller firms to meet.

Google told website owners and app publishers last month they

would have to get consent for targeted ads on behalf of each of

their digital-ad vendors or risk being cut off from Google's ad

network.

At the same time, Google told digital-ad vendors using its

products they would be blocked from targeting any user who hadn't

given specific consent to the vendors and to each of their

partners, according to a letter reviewed by The Wall Street

Journal.

Facebook has started showing its 277 million daily users in

Europe detailed prompts urging them to approve Facebook's use of

their personal information, including sensitive items such as

religion. One pop-up asks permission for Facebook to use data from

other sites and advertisers to target ads at people on all of its

apps, as well as on other websites where it sells ads.

Digital advertising companies, known as ad tech firms, say

Google and Facebook's strict interpretation of GDPR squeezes their

business. The ad tech firms embed their own technology in

publishers' websites and apps, putting them in competition with the

tech giants.

Unlike the giants, the ad tech firms have no direct relationship

with consumers. They say Google's and Facebook's response pressures

publishers to seek consent on behalf of dozens of ad tech firms

that people have never heard of.

Irked internet users are apt to click "no," the ad tech firms

say. Or, publishers may decide it's simpler to just stop using

smaller ad-tech companies.

A digital-advertising firm called AdUX recently closed a service

that harvested location data from people's smartphone apps to show

them targeted ads, said CEO Cyril Zimmermann, because his firm had

little hope of asking for -- much less getting -- consent from

users. Instead, AdUX will aggregate data from bigger companies. He

said the shift has cut into revenue.

"For them, it's easy," he said. "The problem is, who knows

AdUX?"

Some advertisers are planning to shift money away from smaller

providers and toward Google and Facebook, the smaller firms say.

"They are moving their money where there is clear, obvious consent.

The huge platforms are really profiting," said Joachim Schneidmadl,

chief operating officer for Virtual Minds AG, which owns ad tech

firms in Germany.

"We're aware that our customers and partners...have significant

obligations under these new laws," Google said in a blog post

published when it informed partners of its policy changes.

Asked by the Journal about its policy, Google said, "Under

existing EU law, Google already requires publishers and advertisers

to get consent from their end users for the use of our advertising

services on their websites. We're asking our partners to refine the

way they get consent for the use of Google's services on their

sites, in line with GDPR guidance."

At Facebook, Emily Sharpe, a privacy and public-policy manager,

said the firm has created a website and is holding workshops to

help small and medium-sized businesses comply. CEO Mark Zuckerberg

recently told the U.S. Congress: "A lot of times regulation by

definition puts in place rules that a company that is larger, that

has resources like ours, can easily comply with but that might be

more difficult for a smaller startup."

The EU's Ms. Jourová said she believes European national

regulators charged with enforcing the law "will focus on those who

can potentially do the biggest harm to the privacy of people, and

here I do not speak about small companies."

"On big guys increasing market share? I don't believe [the law]

will have such a consequence," said Ms. Jourová.

It's not as though Facebook and Google ever could hope to face

no headaches from the law. Activists have vowed to file complaints

against them.

Scrutiny will be high following revelations in March that

Facebook let political-data firm Cambridge Analytica siphon

personal information of as many as 87 million users without their

consent. The new law authorizes fines of up to 4% of a violator's

global annual revenue, or EUR20 million, whichever is larger.

Court battles over whether companies are meeting GDPR's

requirement that consent be "freely given" are likely to drag on

for years, potentially delaying their practical impact, said

Eduardo Ustaran, a privacy lawyer at Hogan Lovells.

In the meantime, Google and Facebook are building on their

powerful positions in the digital ad market. They have reams of

information on hundred of millions of people who use their websites

and apps in Europe. They also use "share" buttons and ad tools on

millions of websites to collect data on how people use the

internet. That is important information for determining consumers'

interests before showing them ads.

In one study of 850,000 internet users last year, mainly in the

U.S. and Europe, Google tracked 64% of all pages loaded by mobile

and web browsers and Facebook tracked 29% -- more than double the

next-biggest tracker, according to Cliqz, which makes anti-tracking

tools for consumers. The two giants are expected to collect a

combined 49% of all digital ad spending world-wide in 2018, says

eMarketer.

That heft multiplies the advantages they have in requesting

consent. Even if a large number of users opt out of targeted ads

from Google and Facebook in Europe -- something Facebook says it

hasn't seen -- the two will remain by far the largest sources of

consenting consumers, making the duo must-buys for advertisers.

"I'm stumped at how this will fundamentally change Facebook's ad

revenue" or "impact the targeting of Google search," said Mark

Mahaney, an analyst at RBC Capital Markets.

The idea of requiring consent to use personal information

stretches back to the 1970s, when countries began passing

data-protection laws. Germany's 1977 law helped shape Europe's

future approach: It forbade all but a few narrow uses of personal

information without an individual's permission -- which had to be

in writing.

With the rise of the internet in the 1990s, the EU decided to

harmonize privacy rules. The definition of consent remained

somewhat open, referring to any "specific and informed indication

of wishes." The new law says consent must be "unambiguous" and

communicated "by a statement or by a clear affirmative action."

That effectively rules out the widespread practice of

pre-checked boxes. Consent in the EU becomes something that is

"opt-in" rather than "opt-out," regulators say.

Business-lobby groups howled when the text was made final in

2015. Smaller companies soon were ringing alarm bells.

"The politicians wanted to teach Google and Facebook a lesson.

And yet they favor them," a Brussels lobbyist for an

media-measurement firm said at the time.

Once the law passed in spring 2016, Google and Facebook threw

people at the problem. Google involved lawyers in the U.S.,

Ireland, Brussels and elsewhere to pore over contracts and

procedures, said people close to the company. Facebook mobilized

hundreds of people in what it describes as the largest

interdepartmental team it has ever assembled.

Facebook lawyers spent a year scrutinizing the law's lengthy

text. Designers and engineers then toiled over how to implement

changes, according to Stephen Deadman, Facebook's global deputy

chief privacy officer.

During the process, Facebook got frequent access to regulators

across Europe. It met with Helen Dixon, the data protection

commissioner in Ireland, where the company bases its European

operations, and her staff to run through changes Facebook was

planning. Ms. Dixon's agency provided the firm with feedback on the

wording of its consent requests, Facebook made.

"We've been getting their guidance over many months," Mr.

Deadman says.

Ms. Jourová, the EU's justice commissioner, said the tech giants

seemed scared when she met with them in Washington a year ago.

Google and Facebook then went from trying to fight GDPR to deciding

to use it to their corporate advantage, said a person familiar with

the meetings.

Travelling to Silicon Valley in September, this person said, Ms.

Jourová sat down with Facebook officials to discuss privacy, with a

drop-in visit from Facebook Chief Operating Office Sheryl Sandberg.

The next morning, at a meeting at Google headquarters, employees

spent much of a two-hour breakfast meeting taking Ms. Jourová

through Google's approach to compliance.

In mid-April, just before unveiling new opt-in consent pages,

Facebook started running ads in European newspapers saying the new

law "means better protection" and Facebook will ask users to

"review how we can use your data." Analysts at Barclays said last

week they expect the opt-ins will have a low-single-digit impact on

Facebook revenue, and might end up being immaterial.

"We've hit the mark," Mr. Deadman says. "We'll be fully

compliant."

Some publishers and ad tech firms, particularly in Germany, were

taking a different approach. Fearing users would consider detailed

consent forms intrusive, they zeroed in on an exception in the GDPR

called "legitimate interest."

It would let companies use personal information without asking

for consent so long as they took other strict privacy measures. The

companies remained confident in the strategy even after EU privacy

regulators raised questions in February about the validity of using

that exception for marketing-related tracking across multiple

devices or websites, as many firms do.

Then in March, Google forced the issue. It published an updated

"User Consent Policy" that will, as of May 25, require publishers

and app owners that sell ads through Google to request consent that

specifically mentions every company that might collect or process

their users' data, or risk being kicked off Google's system,

according to a copy seen by The Wall Street Journal.

Because Google is involved in so many layers of the ad business,

some publishers say they have no choice but to comply, and others

say they're not sure what they'll do yet. "It's the classic Google

approach: Either you take it or leave it," said Carsten Schwecke,

chief digital officer of Media Impact, Axel Springer's media sales

division. "It is not a pleasant situation for a publisher like

us."

Third-party data collectors that rely on websites to reach

consumers, meanwhile, worry that Google's stance on consent will

cut into their businesses.

"If you put the list of 120 companies on your home page, how is

a user going to make an informed decision?" said Alain Levy, chief

executive of Weborama, a Paris-based ad tech company. "We are a B2B

company. We have no relationship with the consumer."

Some ad-tech companies have decided to pull out of Europe.

Verve, which helps marketers target people with ads using location

data, said last week it will shut its European operations,

including offices in London and Munich, because it feared

publishers wouldn't get consent from enough consumers, said Julie

Bernard, chief marketing officer.

Drawbridge, which helps marketers track users as they switch

from one device to another, also abandoned its ad business in

Europe as a result of GDPR, shutting its London office, said a

spokesman for the California-based company.

Publishers worry that without a thriving third-party ecosystem

of companies that can help them sell targeted digital advertising,

they will be forced increasingly to turn to Google and Facebook --

which also compete with them to sell ads on their own websites.

That would further increase the big companies' market share.

In an attempt to cut a path to consent for these smaller tech

firms, online-ad trade group IAB Europe has put together a

standardized system for websites and apps to ask for user

permission on behalf of the sometimes dozens of companies that

collect data or place advertising on a given destination. Vendors

feed information into the system about what they do with users'

data, and their listings are available for the publishers to

display in their consent requests.

As of Friday, only 13 vendors were listed as available to gather

consent through the system, according to an IAB Europe website.

"It is paradoxical," said Bill Simmons, co-founder and chief

technology officer of Dataxu, Boston-based company that helps buy

targeted ads. "The GDPR is actually consolidating the control of

consumer data onto these tech giants."

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

April 23, 2018 22:33 ET (02:33 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

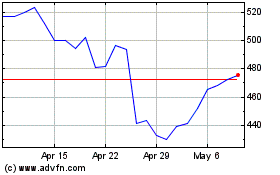

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Meta Platforms (NASDAQ:META)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024