How Century Aluminum Won a Lonely Fight for Tariffs

March 22 2018 - 8:29AM

Dow Jones News

By Bob Tita

In an industry hollowed out by decades of foreign competition

and plant closings, a little-known aluminum maker became the

leading advocate for tariffs that most of its competitors didn't

want.

Century Aluminum Co. emerged as the de facto face of the U.S.

aluminum industry when President Donald Trump invited Chief

Executive Michael Bless to the White House earlier this month to

discuss his tariff plans, rather than leaders of larger firms with

plants in the U.S.

The president's 10% tariff on imported aluminum, which takes

effect Friday, validated the years that Century executives spent

lobbying for trade protections despite opposition from larger rival

Alcoa Corp. and other companies that import some aluminum from

Canada, the Middle East and Asia.

"Our industry has been devastated for years, and nobody was

talking about it," said Jesse Gary, Chicago-based vice president

and general counsel of Century. "We had to stand up for it."

Century cobbled together support for the tariffs from the United

Steelworkers union and small, private companies that make aluminum

components. Century executives founded a trade group, the China

Trade Task Force, to argue that rising aluminum production in Asia

and the Middle East was to blame for falling employment at aluminum

plants in the U.S.

Mr. Trump has said protecting U.S. jobs is a main goal of the

tariffs, along with ensuring a domestic supply of the metal for

defense and national security infrastructure.

Century and Alcoa are the only companies that operate aluminum

smelters in the U.S. Century, which was spun off from Swiss mining

and commodities conglomerate Glencore PLC in the mid-1990s,

generated about two-thirds of its $1.5 billion in sales last year

from its U.S. operations. The company also makes aluminum in

Iceland.

Mr. Gary said Century executives decided to lobby for tariffs in

2015 as plunging oil prices touched off a broader commodity bust.

The price of aluminum dropped 40% that year, and Century idled

nearly all of the lines at its three U.S. smelters.

Century and other companies blamed the drop on a glut of

aluminum production in China that they said was flooding the world

with cheap sheet, plate and extruded shapes. Century said it needed

tariffs to keep that government-backed production from undercutting

prices in the U.S. or entering the U.S. duty-free through other

countries.

"They became the most visible advocate for the tariff," said

Lloyd O'Carroll, an industry analyst in Virginia. "Even though it's

a small company, it was quite vociferous."

Alcoa, which made just about 14% of the aluminum it produced

globally last year in the U.S., opposed the blanket tariff. The

Pittsburgh-based company has been critical of companies in China

overproducing aluminum, but supports reining them in through

negotiated reductions instead of the Trump administration's

strategy of a sweeping tariff on all the world's aluminum.

The industry's trade group, the Aluminum Association, also is

opposed to the tariff. Many of the association's members make

finished goods like parts for cars and airplanes with imported

aluminum that will be subject to tariffs. They say there isn't

enough production capacity in the U.S. to meet aluminum demand

without imports. There are already U.S. tariffs on specific

aluminum products from China, such as foil.

U.S. manufacturers and aluminum processors consumed 11 million

metric tons of aluminum last year, while Century and Alcoa produced

just 748,000 metric tons of raw aluminum here. Imports made up more

than half of the difference, alongside aluminum from recycled

scrap.

A spokesman said Alcoa is pleased that imports from Canada and

Mexico will be exempted from the tariffs and wants additional

exemptions granted for other countries that trade aluminum fairly.

Alcoa and the Aluminum Association say the tariff will discourage

other countries from working with the U.S. to discourage

overproduction in China.

"You'll end up penalizing countries that agree with us," said

Aluminum Association spokesman Matt Meenan.

Rising electricity costs in the U.S. and the construction of

lower-cost smelters abroad contributed to the closure of nearly 20

U.S. smelters since 2000. Most have been demolished, including

Century's smelter in Ravenswood, W.Va.

Century's Mr. Gary predicted the tariff and rising demand could

lead companies to restart up to 1 million metric tons of annual

U.S. production capacity. He said electricity costs are no longer

the liability they once were. An abundance of cheap natural gas

used to generate electricity has brought down power costs in the

U.S. Electricity accounts for almost half the cost of producing

aluminum in a smelter.

The new owner of an idle aluminum smelter in southeast Missouri

plans to restart about 60% of the plant's production capacity this

year after securing an electricity contract. The plant has been

closed for two years.

After Mr. Trump committed to the tariff this month, Century said

it would double both its production and workforce at a Kentucky

smelter. Alcoa was already planning to partially restart a smelter

in southern Indiana this year before the tariffs were

announced.

"You're seeing production come back on," said Mr. Gary. "We

think the right remedy was reached."

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

March 22, 2018 08:14 ET (12:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

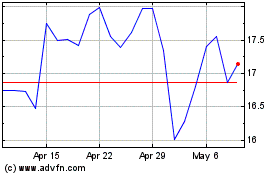

Century Aluminum (NASDAQ:CENX)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

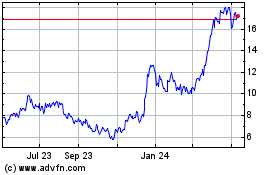

Century Aluminum (NASDAQ:CENX)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024