Why Bond Investors Aren't Worried About Corporate America's Rising Debt Load

March 10 2018 - 7:30AM

Dow Jones News

By Daniel Kruger

U.S. corporate debt has climbed to levels that have coincided

with recent recessions. Many analysts and investors are

unconcerned.

Even before this week's blockbuster $40 billion bond sale by CVS

Health Corp., corporate debt stood at 45% of GDP, a level it last

reached in 2008 as the economy was entering a recession, according

to Moody's Investors Service.

Some companies with weaker credit quality are finding it easier

to access the bond market, and others are skimping on covenants

protecting investors. Yet analysts say the differences between the

current period and 2008 and 2001 -- when corporate debt rose to

similar levels as the U.S. tipped toward contraction -- are more

important than any similarities.

Today, signs of economic growth persist, supported by corporate

tax cuts and a stimulative budget deal, as well as borrowing costs

that remain relatively low by historical standards. That means

companies can continue to borrow without creating significant

economic risks, according to analysts.

Moody's predicts the economy will grow 2.7% this year and

expects the default rate on corporate bonds to drop to 2.2% by

year-end from 3.2% in January.

Today's credit conditions are also stronger than in the past

because of larger capital buffers held by U.S. banks as part of

more stringent regulatory standards, Moody's analysts said.

Banks' bondholdings have shrunk drastically since the financial

crisis, in part because of Dodd-Frank banking reforms but also

because investors are more willing to buy the securities they

underwrite. This signals an improved capacity within the economy to

handle the present level of corporate borrowing.

Banks formerly held significant amounts of bonds either as

unsold inventory from or with their proprietary trading units. In

January 2008, the bond dealers in the Federal Reserve's network of

primary dealers who underwrite the U.S. Treasury debt held as much

as $279 billion of corporate debt on their balance sheets compared

with $24 billion as of last month.

Corporations are in a better position to function with higher

debt burdens than in the past, some analysts said.

"The difference this time is really in the debt affordability,"

said Anne van Praagh, head of credit strategy & research at

Moody's Investors Service.

The yield on the 10-year Treasury note, which serves as a

benchmark lending rate for companies, has climbed this year,

recently hitting a multiyear high of 2.943%, compared with an

average rate of 4.63% in 2007. And with credit spreads -- the

difference in yield between corporate bonds and Treasury debt --

hovering near multiyear lows, investor demand continues to hold

down borrowing costs for most companies.

The lower rates mean that interest payments represent a smaller

share of a given company's cash flow, said Peter Strzalkowski, a

bond portfolio manager at OppenheimerFunds Inc. Many companies have

taken advantage of low longer-term interest-rates to extend the

maturities of their debt and don't face an imminent need to repay

their loans, he said.

Not every observer is so sanguine about the rise in company debt

levels. Such a climb in the late stages of an expansion tends to

happen as companies become increasingly likely to pursue strategies

intended to boost their stock prices, such as share buybacks, or

growth that is no longer happening organically, such as through

mergers or acquisitions, said David Ader, chief macro strategist

for Informa Financial Intelligence.

Both buybacks and M&A activity are heating up. CVS sold

bonds Tuesday to help pay for its acquisition of health insurer

Aetna Inc. Qualcomm Inc. has also offered to buy NXP Semiconductors

for $44 billion in a deal which could be financed in part by bonds.

Other pending deals include United Technologies Corp.'s $23 billion

planned purchase of Rockwell Collins and Bayer AG's $57 billion

expected acquisition of Monsanto Co.

Yet companies appear to be dodging the most-obvious pitfalls, by

doing things like extending their repayment dates, some analysts

said.

A rise in outstanding corporate debt late in an expansion tends

to coincide with periods of Fed rate increases. Under those

conditions, companies with large short-term debts have to refinance

when borrowing costs are rising, said Steven Ricchiuto, chief

economist at Mizuho Securities USA. As company cash flows get

diverted to higher interest payments, less of it becomes available

for wages and investment, curbing growth and inflation, he

said.

Rising interest costs also "squeezes profitability," leading to

slower wage growth, reduced business investment and layoffs, he

said. So far for this expansion, "that is not happening."

Write to Daniel Kruger at Daniel.Kruger@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

March 10, 2018 07:15 ET (12:15 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

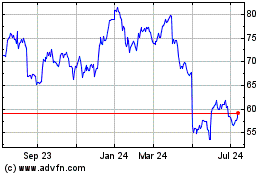

CVS Health (NYSE:CVS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

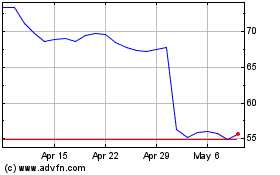

CVS Health (NYSE:CVS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024