By Thomas Gryta, Joann S. Lublin and David Benoit

Jeffrey Immelt, the longtime boss at General Electric Co., was a

polished presenter who held court each year at a waterfront resort

off Sarasota, Fla., where industrial executives and Wall Street

listened for his outlook on the conglomerate.

"This is a strong, very strong company," Mr. Immelt said at the

event last May.

On that Wednesday morning, though, he looked shaky to some

people in attendance, running quickly through highlights of 27

slides in the ballroom of the Resort at Longboat Key Club. He

defended his long-held 2018 profit goal, an optimistic benchmark

Wall Street had long abandoned.

"It's not crap. It's pretty good really," he told the room,

referring to GE's recent financial performance. "Today, when I

think about where the stock is compared to what the company is,

it's a mismatch."

It was a mismatch. On that day, GE shares were trading near $28.

They would go on to collapse over the next six months while the

stock market set fresh records. Today, they trade below $15.

GE's precipitous fall, following years of treading water while

the overall economy grew, was exacerbated, some insiders say, by

what they call "success theater." Mr. Immelt and his top deputies

projected an optimism about GE's business and its future that

didn't always match the reality of its operations or its markets,

according to more than a dozen current and former executives,

investors and people close to the company.

This culture of confidence trickled down the ranks and even

affected how those gunning to succeed Mr. Immelt ran their business

units, some of these people said, with consequences that included

unreachable financial targets, mistimed bets on markets and

sometimes poor decisions on how to deploy cash.

"The history of GE is to selectively only provide positive

information," said Deutsche Bank analyst John Inch, who has a

"sell" rating on the stock. "There is a credibility gap between

what they say and the reality of what is to come."

Said Sandra Davis, who knows several GE executives as the

founder of MDA Leadership Consulting: "GE itself has never been a

culture where people can say, 'I can't.' "

Within weeks of the May meeting, Mr. Immelt announced his

retirement. By year-end, GE under a new leader had cut its dividend

in half and triggered a restructuring that is expected to eliminate

thousands of jobs and cast off more than $20 billion worth of

assets. Today, federal regulators are examining GE's accounting for

certain transactions, and new CEO John Flannery is considering

breaking up the 125-year-old company.

The tumble is all the more stark for a company that embodied the

managerial success of American business and its industrial power.

GE once had the highest market value of any U.S. corporation. Its

alumni have gone on to run companies such as Boeing and

Chrysler.

Few knew just how badly ailing the American icon was. Even GE's

board didn't realize the depth of problems in the biggest division,

GE Power, until months after directors had replaced Mr. Immelt,

according to people familiar with the matter. For the 2017 fourth

quarter, GE reported lower revenue and, after a charge related to a

review of its insurance business, a loss of nearly $10 billion.

"Many of us are in some level of shock," said a former

director.

Investigations are under way inside GE, including at the board

level, seeking to determine how it all happened, some of the people

said.

Several GE executives were aware the 2018 profit goal of $2 a

share wasn't realistic, they said, and some were surprised Mr.

Immelt stuck to it at the May event.

"I led GE through multiple industry cycles, 9/11, recessions,

and the global financial crisis. My leadership team always focused

on the task at hand," Mr. Immelt, 62 years old, said in a written

statement. "Because we had a culture of debate and external

competitiveness, GE built a set of industrial businesses that lead

in their markets."

At a conference hosted by Axios in November, the month after he

stepped down as chairman ahead of schedule, Mr. Immelt noted that

GE is "125 years old; we go through cycles," and said he was "fully

confident that this company is going to thrive in the future."

A spokesman for the former CEO pointed to his decision to

purchase $8 million worth of GE shares in 2016 and 2017. That

included 100,000 shares in mid-May at a price roughly twice

today's.

Former GE Chief Financial Officer Keith Sherin, who worked

alongside Mr. Immelt during challenges such as the financial

crisis, said the CEO would methodically approach a problem with his

team, consider multiple viewpoints and communicate regularly with

the board, making sure executives stayed focused on the most

important issues. "I never found him to be overly optimistic," said

Mr. Sherin, who retired in 2016.

But Mr. Immelt didn't like hearing bad news, said several

executives who worked with him, and didn't like delivering bad

news, either. He wanted people to make their sales and financial

targets and thought he could make the numbers, too, they said.

The optimism was evident in how Mr. Immelt and the board used

the company's cash. Over the past three years, GE spent more than

$29 billion on share repurchases, at an average price of almost

$30, twice the current level. That included billions of dollars

spent less than a year before GE suddenly found itself strapped for

cash last fall.

Mr. Immelt won applause from those who believed in him. Trian

Fund Management LP, which invested $2.5 billion in GE in 2015,

wanted it to buy back even more stock. The activist investor urged

the company to borrow $20 billion for repurchases (which it didn't

do), based on a belief that the profits Mr. Immelt was promising

would send the stock soaring when they arrived.

Instead, at Mr. Immelt's retirement in August the stock was

below its level when he took over 16 years earlier. Including

dividends, GE gained 8% with Mr. Immelt at the helm, while the

S&P 500 rose 214%. Since he stepped down, the stock has lost

about 43%, erasing almost $94 billion in market value. The

relationship with Trian deteriorated last year and the investor

successfully pushed for a board seat to assert influence.

Mr. Immelt's successor, Mr. Flannery, was one of his

lieutenants, a 30-year GE veteran. In November, Mr. Flannery

slashed the 2018 financial targets his former boss had stuck with a

few months earlier. Instead of $2 a share GE now projects $1 to

$1.07. Gone now are most of Mr. Immelt's team, including his

finance chief and head of the power division.

"GE's customers, investors and employees want us to focus on the

future. We are building a stronger, simpler GE," Mr. Flannery said

in a written statement. "In the last decade, the GE team built a

number of excellent businesses."

Several directors discussed in November whether the entire board

should be fired, according to people familiar with the meeting.

Instead, what had been an 18-person board will lose half its

members but soon add three new directors in coming months.

Mr. Immelt's predecessor, Jack Welch, delivered steady profit

growth and sent shares soaring in the 1980s and '90s by striking

deals and aggressively slashing costs and jobs. Mr. Welch also

built up a huge lending business called GE Capital that for years

generated outsize profits -- but nearly sank the company during the

financial crisis on Mr. Immelt's watch.

When GE later sold most of GE Capital, Mr. Immelt laid out a

strategy in which the industrial businesses would grow enough to

offset the lost cash flow from the financial unit, so that GE's

long-term financial projections and dividend were sustainable. It

didn't work out that way. Free cash flow wasn't sufficient to cover

the dividend for years.

During his tenure, Mr. Immelt ramped up research spending and

hired thousands of programmers to develop software for the

machinery GE makes. Results were strong at two of GE's big units,

aviation and health care (medical equipment). But sales and profits

slumped at the enlarged oil and power units, creating serious

problems.

Starting early in his tenure, Mr. Immelt bet heavily on the

energy boom. Acquiring companies that help drillers pump and

transport fuel, he had GE spend more than $14 billion over 10

years, most of it based on higher oil prices than today's.

He also spent more than $10 billion to scoop up assets from a

turbine rival, a transaction that closed just as that market was

cooling. The deal was a 2014 agreement to acquire Alstom SA's power

business, one of GE's biggest industrial acquisitions and a key

part of Mr. Immelt's strategy.

Mr. Flannery, then in charge of business development, favored

the deal. "The power sector is core to GE's future and it has

excellent long-term growth prospects," he said after the 2014

announcement. Now the new CEO says the price was too high.

The acquisition suffered in part because of an 18-month

regulatory review in Europe. To get the deal done, GE had to make

sure French jobs were secure and shed certain assets and

technology.

Some GE executives were concerned the compromises changed the

calculation too much. Alstom's power business suffered while the

sale was in limbo, and some in the leadership at GE wondered if it

should walk away. Mr. Immelt and power division leaders were

determined to close the transaction, people familiar with the

decision said.

Defenders of the deal say it gave GE a much larger base of

customers for its services and provided technology to produce a

more efficient gas turbine. While the timing wasn't ideal, said one

person close to the transaction, the company couldn't control when

such assets became available.

"When the EU delayed the deal, GE should have walked away," said

Scott Davis, an analyst at Melius Research. "The fatal move,

however, was how GE acted after the deal closed."

Rather than using his unit's greater size to raise prices, GE

Power's then- CEO Steve Bolze moved to gain market share,

undercutting rivals such as Siemens AG to win sales for GE's

biggest gas turbines, analysts say.

At the time, Mr. Bolze was among those competing to be the next

head of GE. He was bullish on the power unit's prospects in March

2017 but warned of possible volatility. "I am not naive on the

market," Mr. Bolze said at an investor meeting that month,

predicting a flat market for the biggest turbines. In June, days

after losing out for GE's top job, Mr. Bolze said he would

leave.

It wasn't until a meeting in September that the board learned

the depths of the problems at the division, which accounts for 30%

of GE's approximately $122 billion in annual revenue. GE Power was

sitting on too much unsold inventory and was discounting deals to

hit sales projections.

Mr. Immelt's optimism was part of the problem, according to some

people close to the situation. They said he told the board that

management had identified risks in the power business, yet

downplayed them. The probability and risk were way off, one

said.

Mr. Immelt's spokesman said the board and executive team were

informed of the company performance and were involved in setting

financial targets.

Orders in the power division dropped 25% in the fourth quarter

of 2017 from a year earlier, and the unit's profits for the full

year fell by nearly half to $2.8 billion. In December, GE said it

would cut 12,000 jobs in the power business, or nearly 18% of the

division's workforce, and has replaced much of the management of

the unit.

Lisa Davis, the U.S. chief of Siemens, said the German company's

executives "have seen this decline coming for the last several

years." So Siemens had reduced its capacity in its power business,

she said, while GE bought more.

GE also had been selling upgrades to make existing gas turbines

run more efficiently. As recently as July, it was telling investors

it would sell as many as 165 so-called advanced gas path, or AGP,

upgrades in 2017. In October, the company cut that target in half,

and it said it expects to sell just 40 upgrades in 2018.

Some analysts have expressed concern GE's accounting for the

upgrades masked pressure on the division. According to former

executives, the upgrades meant lower service fees for customers, in

exchange for one-time upgrade costs, meaning that future sales were

being pulled forward.

GE disclosed last month that the Securities and Exchange

Commission is examining its revenue recognition practices around

such contracts.

The agency also is seeking information about a recent GE review

of its insurance business that prompted a $6.2 billion

fourth-quarter charge and a plan to set aside $15 billion over

seven years to bolster insurance reserves at the now-shrunken GE

Capital unit. GE said it is cooperating with the inquiries. The SEC

declined to comment.

It's clear more changes are in store, for both employees and

investors. Last month, Mr. Flannery said he was examining whether

to separate some of GE's core units.

That was a sharp contrast to one of Mr. Immelt's last

predictions. "I view 2017 as the last big restructuring year in the

company," Mr. Immelt said at the conference in Sarasota in May. "So

this noise is going to kind of come out of the system."

--Ted Mann contributed to this article.

Write to Thomas Gryta at thomas.gryta@wsj.com, Joann S. Lublin

at joann.lublin@wsj.com and David Benoit at

david.benoit@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

February 21, 2018 11:52 ET (16:52 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

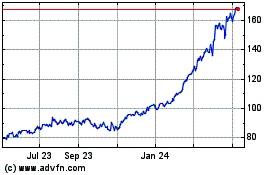

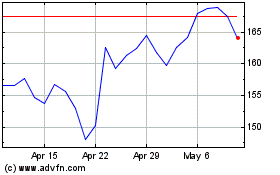

GE Aerospace (NYSE:GE)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

GE Aerospace (NYSE:GE)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024