Medtronic's chief executive officer, Omar Ishrak, says

'value-based' contracts are the future

By Peter Loftus

This article is being republished as part of our daily

reproduction of WSJ.com articles that also appeared in the U.S.

print edition of The Wall Street Journal (February 20, 2018).

Omar Ishrak, chief executive of Medtronic PLC, sees a future in

which medical-technology companies accept more risk in how they get

paid for their products.

Medtronic, the world's largest medical-device maker,

specializing in such products as implantable cardiac devices and

insulin pumps, is increasingly signing supply contracts with

customers that adjust prices based on how well the products work in

patients, rather than simply having the customer pay a fixed

per-unit cost regardless of a device's performance in individual

patients.

Mr. Ishrak, at the helm of the Dublin-based company since 2011,

says the deals are part of a broader shift to "value-based" health

care -- holding providers and manufacturers financially accountable

for patient outcomes.

Since early last year, Medtronic has signed nearly 1,000

contracts that require it to reimburse hospitals for certain costs

if an antibacterial sleeve called Tyrx doesn't ward off infections

in patients who get cardiac-device implants. It also has a deal

with Aetna Inc. to tie a portion of the reimbursements the insurer

pays for Medtronic's insulin pumps to whether diabetes patients

improve after switching to the pumps. The company is exploring

contracts with insurers that would link reimbursement for its new

MiniMed 670G insulin-pump system to the system's ability to prevent

low blood-sugar episodes in patients, as measured by the system's

blood-sugar monitor, Mr. Ishrak says.

Mr. Ishrak, who is 62 years old and trained as an electrical

engineer, spoke recently with The Wall Street Journal about the

company's foray into outcomes-based contracts. Edited excerpts

follow.

WSJ: Why outcomes-based contracts?

MR. ISHRAK: Medtronic is focused on technologies to improve

outcomes. We use biomedical engineering to alleviate pain, restore

health and extend life. Historically we've done that by creating

credible evidence that our technologies do change outcomes. But at

the end of the day, we and the industry get paid on the technology

itself and a promise that those outcomes will actually be

changed.

We are moving, just like the rest of health care, to a

value-based model, where we get paid in some fashion for actually

achieving the outcome. It's a step we have to take to make sure

that the value we create with our technologies is truly realized.

And when it gets realized, we will get paid fairly for it.

Additional assurance

WSJ: Do you see this primarily as a way to reduce costs, or to

provide additional assurance that customers are getting what they

pay for?

MR. ISHRAK: I think it's more the latter. The entire health-care

system actually gets the benefit of the money that they spend for

certain kinds of treatment, of which technology is a part. So this

is not going to happen by ourselves.

WSJ: How will this benefit patients?

MR. ISHRAK: Patients benefit because when I say improve

outcomes, if you look at the words "alleviate pain, restore health

and extend lives," this means improving outcomes that are

meaningful for patients. If they're assured that the entities who

are treating them are actually accountable financially to make sure

that their outcomes are improving, then I think that's very

meaningful for patients.

WSJ: How much of your business could these contracts cover?

MR. ISHRAK: My aspiration would be that all of our revenue gets

paid through, or is at least tied in some fashion to, some kind of

outcome-based measurement. And maybe a portion of that is at

risk.

The first task we have is, what outcome are you going to

measure? Is it really meaningful for patients? Can it be measured?

Can it be baselined? Can you proactively monitor it?

We've started by kind of making contracts in areas where there

are fewer variables, where the outcomes can be measured well.

WSJ: In what areas?

MR. ISHRAK: The one that is most mature and has had the most

success is an antibacterial sleeve on implantable cardiac devices.

The sleeve essentially guarantees prevention of any sort of

infection as a result of the implantation procedure of that

device.

Here we take a certain cohort of patients, where the risk of

infection is the highest. And we say to a provider that we will be

responsible for any incurred costs for that provider on that

patient if there is a reinfection. Total cost. Not simply the value

of the sleeve but the whole cost of the procedure we will be

responsible for if there is an infection.

That program has really taken off.

WSJ: Are there cases where you had to pay back costs?

MR. ISHRAK: Almost none. Very, very few.

Growth areas

WSJ: Where will this grow?

MR. ISHRAK: One area is chronic-disease management, a continuous

effort to prevent escalation of a disease. For that you need

periodic measurements of clearly identified outcome measures, which

could be clinical markers, such as the blood-glucose level in a

diabetic patient. Or it could be a blood-pressure measurement of

some sort. You may also have outcome measures tied to their

activity levels, whether they can walk around, climb stairs.

It could be a variety of things that are meaningful for patients

that are measured on a periodic basis, and the payment is done

according to the different organizations who are participating --

their ability to keep a patient or group of patients within a

certain range of these measurements.

WSJ: Why aren't more device companies doing this?

MR. ISHRAK: It's difficult to do. Incentives for the whole

health-care industry don't encourage this. You get paid for a

service; that's easier than being paid for an outcome. You get paid

for a technology; that's easier than getting paid for the

technology actually doing something. So the incentive structures

across multiple stakeholders, almost every stakeholder, are

fashioned to make this a risky proposition.

The fee-for-service model is just not a sustainable model, and

we have to do our piece in a managed way, a responsible way, to

move the ball forward. I think there's general agreement in

med-tech that having some sort of financial connection to the

outcome, or some accountability for the outcome, is a good thing,

and that's important.

Pharma vs. devices

WSJ: In pharma, these types of deals have been held up as a

response to the backlash against high drug prices. In devices, the

patient out-of-pocket cost doesn't seem to be as big an issue.

MR. ISHRAK: I agree. In our industry these models are easier to

create, because we create engineered solutions for which outcomes

are very clearly defined and you know when to expect them, as

opposed to pharma, where outcomes are a little more difficult to

measure and predict. But I'd much rather us get ahead of it as an

industry rather than rightly or wrongly being accused of our prices

being too high or unreasonable or whatever.

WSJ: Are there obstacles to market acceptance of your products,

and do these contracts help overcome those?

MR. ISHRAK: Price is a big market barrier sometimes. Because you

spend money developing something and you expect a better price, and

in many cases there is no objective measure of the value you're

creating. Often in the present model, we sell to providers,

hospital systems, physicians, and although they accept the fact

that the improvement is there and will benefit the patient, the

cost benefit may in fact be realized by a payer -- an insurer, for

example -- because the patient doesn't come back again. But the

hospital really doesn't see that at all, because in fact if the

patient comes back, they get paid again.

WSJ: So your outcomes-based deals are primarily with the

providers, and not the payers?

MR. ISHRAK: Providers, yes. But we're beginning to work with

some payers. We're only scratching the surface and we've only done

it in a few areas. We're certainly encouraged by the progress.

Mr. Loftus is a Wall Street Journal reporter in Philadelphia. He

can be reached at peter.loftus@wsj.com.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

February 20, 2018 18:13 ET (23:13 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

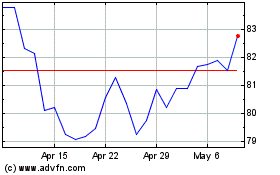

Medtronic (NYSE:MDT)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Medtronic (NYSE:MDT)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024