Hit by tax charge and fixed-income falloff, bank reports $1.93

billion quarterly loss

By Liz Hoffman

This article is being republished as part of our daily

reproduction of WSJ.com articles that also appeared in the U.S.

print edition of The Wall Street Journal (January 18, 2018).

Debt traders at Goldman Sachs Group Inc. stumbled badly in the

last quarter of 2017, generating just $1 billion of revenue. Back

in 2009, they brought in that much every 10 days.

Reporting its fourth-quarter results Wednesday, Goldman said

debt-trading revenue fell 50% -- the worst three-month showing

since 2008 and the latest in a nearly unbroken chain of quarterly

declines in the business.

The numbers reflect problems not unique to Goldman, whose

struggles have been acute, but also a wider malaise that has

settled over Wall Street's securities operations, once the source

of fat profits.

The trouble isn't rogue traders or big bets gone bad, but

shrinking demand from investors who, with little conviction about

how to play the markets, simply sit it out or opt for cheap,

off-the-shelf investment products, such as index funds.

Meanwhile, new regulations have cast banks as mere toll-takers,

and more transparent and accessible data have eroded the

informational edge that once gave them pricing power over their

clients.

The biggest quakes have hit banks' fixed-income divisions,

diverse operations that trade everything from sovereign debt to

precious metals to products tied to global interest rates.

Fixed-income revenue last year at the four biggest U.S. trading

banks -- Goldman, JPMorgan Chase & Co., Citigroup and Bank of

America Corp. -- fell between 6% and 30% from 2016, and remains

orders of magnitude below the peak years of the

pre-financial-crisis boom.

Goldman's trading decline sent the company's stock down 1.8%

Wednesday and ratcheted up pressure on Chief Executive Lloyd

Blankfein to fix the business that vaulted him to the top of the

firm. Mr. Blankfein, a former gold salesman, rose through Goldman's

fixed-income trading division and ran it in the mid-2000s before

being named CEO.

For 2017 as a whole, Goldman's revenue from its fixed-income

business of $5.3 billion was little more than a fifth of what it

was in 2009.

And, for the first time on record, Goldman's investment bankers,

who broker mergers and underwrite securities offerings, outearned

the firm's fixed-income traders.

Goldman's traders struggled all of last year, losing money on

oil and gas trades as well as holdings of low-rated corporate debt.

Nothing clicked in the most-recent quarter, when a continued lack

of volatility kept clients on the sidelines. Goldman cited declines

in all four of its main fixed-income businesses, which include

credit, currencies, commodities and interest rates.

Goldman executives have said they were too slow to recognize

that the effects of the financial crisis would linger as long as

they have.

Over the past two years, the firm has cut traders, trimmed

bonuses, revamped its sales network and embraced the type of

low-margin, high-volume trades it once deemed too trivial to bother

with. Another objective is to win more trading business from

corporate clients that already hire Goldman for boardroom advice

but use rivals to manage their market risks. Goldman itself has

recognized that for too long it has relied on trading revenue from

hedge funds, whose trading business is lucrative but runs hot and

cold, and too little on companies and large asset managers, which

have more predictable, simpler needs.

"We absolutely acknowledge that the business footprint and mix

we have is a consequence of choices that we made over time," Chief

Financial Officer Martin Chavez said on an analyst call Wednesday.

"We know that we need to do better." He said it would take "an

order of months" to see changes produce new profits.

Yet some tweaks, such as a 2015 reorganization of the firm's

corporate sales force, have been in place for longer, with little

to show.

"It just seems like progress should have been a lot faster than

it's been," Mike Mayo, a Wells Fargo analyst, said Wednesday.

The most recent poor quarter is likely to intensify calls for

more dramatic changes, including a shake-up of its broader trading

division's leadership. That idea has gained steam among top Goldman

executives in recent months, according to people familiar with the

discussions.

Overall, Goldman's quarterly earnings, like those of other big

banks, were muddied by the new tax law. A $4.4 billion one-time

charge wiped out the company's entire quarterly profit, producing

its first loss since 2011 of $1.93 billion. Without the charge,

Goldman's net income would have exceeded analyst expectations.

But Goldman disappointed investors by saying it would dial back

its stock-buyback plans to plow earnings instead into areas where

it thinks it can grow.

Those include steadier businesses such as consumer banking and

money management.

Both gained ground in 2017, helping to boost Goldman's full-year

revenue 5%, the best showing among big banks so far. Asset

management added $42 billion in long-term money at a time when

investors are fleeing actively managed funds, and Goldman's

fledgling consumer-lending effort wrote $2 billion in fresh loans.

But those efforts will take years to fill the roughly $15 billion

revenue hole opened by Goldman's trading woes -- if they ever

do.

For the lack of noticeable progress in Goldman's trading

turnaround, another firmwide effort is bearing fruit. A few years

ago, executives decided to make a play for debt-underwriting

business. That business historically has been dominated by big

commercial banks, which can write large checks and tap trillions of

dollars in low-cost deposits to fund them.

Debt-underwriting revenue hit a record $2.5 billion for the year

and in the fourth quarter surpassed that of JPMorgan, Bank of

America and Citigroup. Goldman has made inroads on the back of its

merger bankers, who are more often offering debt, in addition to

advice, when putting together deals.

Write to Liz Hoffman at liz.hoffman@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

January 18, 2018 02:47 ET (07:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

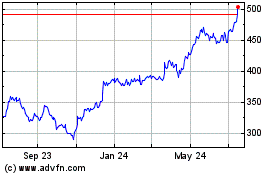

Goldman Sachs (NYSE:GS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

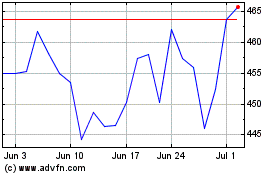

Goldman Sachs (NYSE:GS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024