By John D. McKinnon

This article is being republished as part of our daily

reproduction of WSJ.com articles that also appeared in the U.S.

print edition of The Wall Street Journal (November 24, 2017).

WASHINGTON -- Over just two days this week, the Trump

administration has both sued AT&T Inc. to block its planned

takeover of Time Warner Inc. and proposed allowing internet-service

providers -- like AT&T -- to form closer alliances with content

companies, like Time Warner.

The two government moves seem to go in opposite directions, on

the one hand restricting a major telecommunications merger and on

the other giving internet providers broad new powers to shape their

customers' online experiences.

But the actions reveal one consistency, and what might be viewed

as an emerging Trump administration regulatory philosophy: Instead

of new bright-line rules, such as those put in place under the

Obama administration, it is stressing the enforcement of

longstanding laws and regulations.

The moves are a shift in emphasis from the approach taken by the

Obama administration, which in 2015 adopted highly specific rules

governing internet providers in the name of "net neutrality," the

principle that all web traffic be treated equally. The providers

were prevented from cutting deals, known as "paid prioritization,"

that would give fast lanes to some kinds of content in return for a

price.

And the Obama administration carried that approach into the

antitrust realm, insisting in Comcast Corp.'s acquisition of

NBCUniversal, Inc. earlier this decade that Comcast live up to

elaborate net-neutrality restrictions, as part of the so-called

behavioral remedies that were conditions of antitrust approval.

In other words, net-neutrality regulation took the place of an

antitrust challenge.

Now the tables are turned. When it comes to internet policing,

the FCC will ease back on its rules and turn a measure of oversight

authority to the antitrust cop, the Federal Trade Commission, a

deliberate action outlined Tuesday by FCC Chairman Ajit Pai.

"As a result of my proposal, the Federal Trade Commission will

once again be able to police [internet providers], protect

consumers and promote competition, just as it did before 2015," Mr.

Pai said. "Notably, my proposal will put the federal government's

most experienced privacy cop, the FTC, back on the beat to protect

consumers' online privacy."

In the case of net neutrality, Mr. Pai's FCC moved fairly

quickly by regulatory standards. It is too soon to know whether

this enforcement emphasis will extend to other parts of the Trump

deregulatory agenda, which involves rolling back a broad range of

Obama-era rules covering power-plant emissions, financial services

and other industries.

In the financial sector, Mr. Trump's regulatory team has

launched a review of stricter rules adopted after the 2008

bailouts. In general, officials say they want to recalibrate

standards governing bank lending and other areas without scrapping

them entirely.

It isn't clear whether financial regulators will maintain the

streak of aggressive enforcement actions that began under the Obama

administration. Fines levied by the Securities and Exchange

Commission fell to a four-year low in the last fiscal year, though

SEC officials caution against reading too much into a single year's

data.

At the Environmental Protection Agency, Administrator Scott

Pruitt has touted a "back-to-basics" approach involving the

reversal of numerous Obama regulations and has said he would

emphasize enforcement.

"There's a difference between creating regulatory certainty and

holding polluters accountable for violating environmental laws,"

said EPA spokeswoman Liz Bowman.

Environmental groups say the EPA's actions so far this year

don't suggest a robust emphasis on enforcement. The agency counters

that those groups' estimates are low because it can take months or

years before such an action can be completed.

Consumer groups argue that clear regulations are necessary

across industries to keep companies from harming consumers. With

the internet, they say, antitrust enforcement is too cumbersome,

slow and potentially arbitrary to keep up with the speed of

technological change.

Because the FTC doesn't have the authority to create and enforce

broad rules, it isn't in a position to police fast and slow lanes

that may harm competition, said Jonathan Zittrain, professor of law

and computer science at Harvard University and a former chairman of

the FCC's Open Internet Advisory Committee. The agency can only

take "individual enforcement action on the vague notion of unfair

trade practices," he said.

Conservatives who believe in a lighter-touch regulation, like

Mr. Pai, generally argue that hard-and-fast regulatory rules are

overly prescriptive and will slow investment and innovation.

Some free-market advocates take that even further, saying the

antitrust action this week goes too far, especially given that the

AT&T-Time Warner tie-up is a "vertical" merger, or one that

combines two companies that operate at different stages of a supply

chain.

"If this one [transaction] isn't good, what vertical integration

transaction is going to be good? Virtually none," said Fred

Campbell, director of Tech Knowledge, a free-market think tank and

a former head of the FCC's wireless bureau about a decade ago.

"Isn't it a de facto regulation then that we're just going to

prohibit vertical integration?"

--

Douglas MacMillan

, Ryan Knutson, Ryan Tracy and Timothy Puko contributed to this

article.

Write to John D. McKinnon at john.mckinnon@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

November 24, 2017 02:47 ET (07:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2017 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

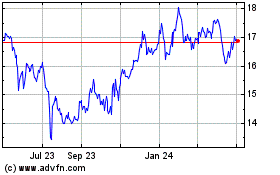

AT&T (NYSE:T)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

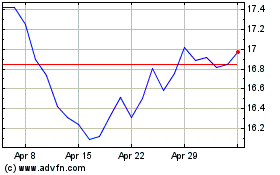

AT&T (NYSE:T)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024