By Rachel Louise Ensign and AnnaMaria Andriotis

To any casual observer, the area just south of Trump Tower in

Midtown Manhattan is obviously wealthy: The blocks are crowded with

skyscrapers, and stores include Versace and Ferrari. Diners can

pick at the foie gras and caviar on La Grenouille's $172 prix-fixe

dinner menu.

In the eyes of federal-bank regulations, though, that sliver of

New York City is a poor neighborhood where median incomes are

relatively low.

The anomaly has yielded a hidden benefit for banks such as J.P.

Morgan Chase & Co. and Wells Fargo & Co. that have crowded

branches into the area. Having robust branch representation in

supposedly low-income areas gives them a better score on a key

regulatory test that can help determine how fast they expand.

It's all part of the Community Reinvestment Act, a roughly

four-decade-old federal law designed to stop lending discrimination

in low-income neighborhoods. In recent years, lawmakers and

regulators have clashed over the legislation's efficacy.

Proponents of the CRA, many on the left, count it as a bulwark

for those struggling to keep up in a financial system that has

grown more unequal. Critics, mostly conservative, say the law's

implementation encouraged banks to make bad loans that contributed

to the financial crisis.

Neighborhoods like the one in Midtown Manhattan could add a new

dimension to the debate, even though branch analysis is only one

part of regulators' broader CRA evaluations. Its quirky treatment

under the CRA is due to the fact that regulators who enforce the

act rely on older, sometimes unreliable, Census Bureau data to

determine an area's income level.

New York isn't an isolated example. Six of the 10 most popular

poor areas for banks to have branches, including the Manhattan

tract, are slated to lose that classification when more recent

census data go into effect this year, according to regulators and

data from fair-lending software company ComplianceTech. But bank

regulators have been using the older data because they stick to a

preset schedule of switching every five years.

In one of these census tracts, a "low income" area in downtown

San Francisco, one of the most expensive cities in the country, 53

branches pack into an area that census data indicate has only 1,783

residents. That's 52 more branches than the average poor district

in the U.S. has, despite the fact the San Francisco tract has far

fewer residents than average.

About 30 miles away in Menlo Park, Calif., a First Republic Bank

branch on Facebook Inc.'s corporate campus is classified as lower

income because the surrounding areas have lower incomes than the

median of the broader area. But the only people with access to the

branch are employees and guests of Facebook, which paid an average

of $189,000 in stock-based compensation last year for each employee

globally. Facebook and First Republic declined to comment.

In Washington, guests of high-end hotels in the blocks near the

White House and elite lobbying firms have 19 branches to choose

from, including three Bank of America Corp. locations. All of the

branches give the banks credit for serving a lower-income

community.

Then there is Manhattan's census tract 102, the bustling Midtown

blocks with the most lower-income bank branches per capita in the

U.S., according to a Wall Street Journal analysis of data from

ComplianceTech's LendingPatterns.com. Due to a paucity of

residential buildings in the area, the district bordered by Park

and Fifth avenues, 49th and 56th streets has only 230 residents, or

about 10 for each of the 22 bank branches that call the tract home,

according to the census data used by banking regulators.

Visitors to the area can stay in the St. Regis Hotel where most

rooms cost more than $1,000 a night or gaze up at the Olympic

Tower, a 51-story skyscraper where fashion's Gucci sisters have

listed a penthouse for $35 million. A short walk away: Trump Tower,

which is in a higher-income district across 56th Street.

Banks have good reasons besides the CRA to be in such areas.

They tend to include commercial districts that are densely

populated with office workers who might want to visit a bank on a

break. Tract 102 also has many tourists visiting. But the areas

often have few residential buildings, one reason that can explain

the lower-income CRA designation. The fact that banks get credit

for branches in these areas, though, has prompted some

criticism.

"Banks can conform to the letter of the law, but not meet the

purpose of CRA," says John Vogel, an adjunct professor at

Dartmouth's Tuck School of Business. This is especially the case,

he says, in the classification of "low- and moderate-income

neighborhoods."

The CRA was signed by President Jimmy Carter in 1977 to stop

"redlining, " a practice where banks wouldn't lend money in poorer

or minority neighborhoods. Bank regulators during the Clinton

administration added a uniform test as a way to measure compliance

more objectively. The hope was that by encouraging banks to do

business in lower-income areas, people living there would be able

to get affordable loans.

The vast majority of banks examined -- approximately 97% --

received a passing grade on the test between 2006 and 2015,

according to a report by the Congressional Research Service.

The penalties for falling short can be costly. In addition to

the reputation hit, a low rating generally prevents banks from

pursuing mergers, which can be a big disadvantage for small and

midsize lenders.

For instance, Mississippi-based BancorpSouth had to delay two

mergers when its CRA rating was downgraded. Other bigger lenders

including Wells Fargo, Fifth Third Bancorp and Regions Financial

Corp. have faced restrictions on mergers or other expansion when

their ratings were downgraded.

First Republic Bank, which caters to wealthier clients including

those at Facebook's headquarters, has 14 branches that count for

CRA credit as lower income. Three of those branches are in those

popular neighborhoods that the newer census data indicate are no

longer low- or moderate- income. On First Republic's most recent

CRA exam in 2015, regulators gave it a "high satisfactory" rating

for the portion of the test that includes examining branch

locations.

The part of the CRA test looking at branch location examines

census tracts, which typically have a few thousand people apiece.

Each tract is typically sorted into one of four groups, based on

the tract's median family income in relation to the broader

metropolitan area's. Tracts in the two poorer groups are called low

or moderate income, nicknamed "LMI."

Banks get better marks on the test for loans or branches that

involve the two lower-income groupings.

In New York's tract 102, the bank regulators estimate that

median family income is $45,019, or 62% of the $72,600 median for

the New York City area. That number is pegged to 2010 census

data.

But since then, the Census collected new data that boosted the

income figure to $111,667, a bounce that's due in part to the

tract's small sample size. In its most recent report, from 2015,

the Census bureau couldn't find enough reliable data to give an

income estimate.

Bank regulators that oversee CRA, which include the Federal

Reserve, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. and the Office of the

Comptroller of the Currency, have continued to rely on the 2010

data, so the tract remained a lower-income one under the CRA

test.

This year, bank regulators are starting to base their income

designations on 2015 census data. The refreshed data, a portion of

which was released by regulators earlier this year, will mean six

of the 10 lower-income tracts with the most bank branches will no

longer merit those designations.

As for Manhattan's tract 102, only about 30 households submitted

data for the latest census survey. It isn't clear if they included

the nine priests who live in the district at St. Patrick's

Cathedral -- with incomes of around $30,000 apiece -- or any

residents of Olympic Tower, where a doorman laughed at the question

of whether the building had low-income residents.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

May 18, 2017 08:14 ET (12:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2017 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

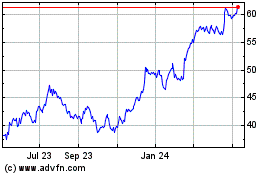

Wells Fargo (NYSE:WFC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

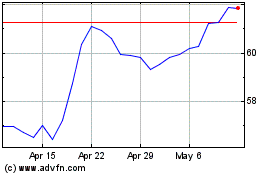

Wells Fargo (NYSE:WFC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024