By Brian Baskin and Laura Stevens

Amazon.com Inc. wants to furnish your home.

The online retail giant is making a major push into furniture

and appliances, including building at least four massive warehouses

focused on fulfilling and delivering bulky items, according to

people familiar with Amazon's plans.

With that move, the Seattle-based retailer is taking on the two

companies that dominate online furniture sales -- Wayfair Inc. and

Pottery Barn owner Williams-Sonoma Inc. Furniture is one of the

fastest-growing segments of U.S. online retail, growing 18% in

2015, second only to groceries, according to Barclays. About 15% of

the $70 billion U.S. furniture market has moved online, researcher

IBISWorld says.

But even the biggest players in online furniture are struggling

to get the market right. Unlike established categories such as

books and music or even apparel, retailers are still hammering out

basic concepts like how much variety to offer on their sites and

the most efficient ways to deliver couches and dining sets to

customers' homes.

While Amazon has been selling furniture for years, it has lately

decided to tackle the sector more forcefully.

"Furniture is one of the fastest-growing retail categories here

at Amazon," said Veenu Taneja, furniture general manager at Amazon,

in a statement. He said the company is expanding its selection of

products, with offerings including Ashley Furniture sofas and

Jonathan Adler home décor, and it is adding custom-furniture design

services. Amazon is also speeding up delivery to one or two days in

some cities, he added.

The retailer already has an approximately 17% market share in

the broader home furnishings category, according to Morgan Stanley,

and it is continuing to gain. That includes smaller items, too,

such as cookware and towels.

While Amazon has disrupted industries from publishing to fashion

with free, fast shipping and easy, app-based one-click buying,

furniture can be a tough sector to crack. For one, it is expensive

to deliver a couch and other big items, and consumers typically

want what are known as "white glove" services, extras like bringing

it into the home, setting it up and removing trash. And while

packing more small packages onto a delivery van brings the costs

down because it can make more stops, you can only fit so many

pieces of furniture onto a truck.

Shoppers are still generally willing to pay for furniture

delivery, but some retailers and logistics companies say they are

facing growing pressure to ship online orders faster. Wayfair

offers free shipping on orders over $49, but delivery times can

range from one or two days to just over two weeks. Pottery Barn

charges on a sliding scale based on price, with delivery costs

running above $100 for more expensive items. Furniture sold and

shipped directly by Amazon is free for Prime members and on orders

over $25, while items sold by third-party sellers may cost

extra.

To guarantee two-day shipping to 99% of consumers, a retailer or

logistics company needs up to a dozen large warehouses spread

around the country, plus around 110 smaller facilities to stage

deliveries to customers' homes, said Troy Cooper, chief operating

officer at XPO Logistics Inc., which manages distribution centers

and fulfills online orders for large retailers like IKEA.

By comparison, a retailer can deliver furniture within a week to

most customers simply by planting a large distribution center on

each coast, similar to how they would manage inventory for

brick-and-mortar stores, Mr. Cooper said.

Amazon is expected to rely on XPO and other third-party

logistics providers to manage distribution centers and handle

delivery of furniture and appliances for the near future, even as

it takes more of its logistics in house in other parts of its

business, people familiar with the company's plans say. Amazon

declined to comment on its delivery plans. XPO declined to comment

on its relationship with Amazon.

Rising sales may be helping reduce delivery costs by creating

better density. Costs go up for transportation companies as

deliveries get more spread out and infrequent.

"Just in the last year, furniture has taken off," said Richard

Phillips, Jr., chief executive at Pilot Freight Services, a Lima,

Pa.-based trucking company that makes larger e-commerce deliveries.

The company's No. 1 business-to-consumer shipment has shifted to

furniture, from TVs.

Pilot is one of many logistics companies building out nationwide

networks to handle bulky items as retailers look for cheaper ways

to ship furniture and appliances ordered online. XPO made 12

million home deliveries last year, up from 9 million in 2015. Estes

Express Lines, one of the largest U.S. trucking companies which is

based in Richmond, Va., started a "final mile" service in December

after noticing retailers were mixing in more home deliveries.

These companies are filling in part a void left by United Parcel

Service Inc. and FedEx Corp., whose executives have complained

about bulky items gumming up distribution centers designed to

process millions of small packages at lightning speed.

"You go for what is the largest segment of the market," said

Carl Asmus, senior vice president for e-commerce at FedEx. "The

sweet spot is not necessarily refrigerators."

Boston-based Wayfair started building out its own delivery

network about a year and a half ago, said Chief Executive Niraj

Shah. The company got into doing its own deliveries because it is

so important in retaining customers. "We built it primarily to

drive quality, but secondarily it certainly gets you cost benefits

at scale," he said.

He said he is not worried about Amazon. The rival is hardly a

new entrant to the space, and it is hard to get the customer

service side of the equation right, he added.

Wayfair on Tuesday reported a nearly 30% increase in

first-quarter revenue from a year earlier, beating most analysts'

forecasts. The company's shares rallied 21% to an all-time

high.

Home deliveries are "exponentially" more expensive but surging

demand makes them worth it, said John Paiva, chief operating

officer at Estes Final Mile. Estes Express Lines plans to expand

its new service to a majority of its more than 200 U.S. terminals

by the end of 2017.

Before launching, Estes spent a year training drivers used to

dealing with warehouse dock workers to interact with ordinary

people, and built a database of instruction manuals for employees

to use when assembling furniture in homes.

"If the driver is having a bad day or doesn't understand the

importance of greeting customers professionally, it can...tarnish

the reputation of the [retailer]," Mr. Paiva said.

Write to Brian Baskin at brian.baskin@wsj.com and Laura Stevens

at laura.stevens@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

May 12, 2017 05:44 ET (09:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2017 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

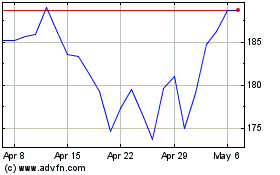

Amazon.com (NASDAQ:AMZN)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

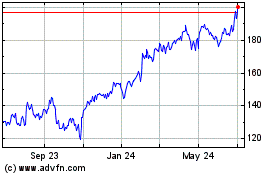

Amazon.com (NASDAQ:AMZN)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024