By Preetika Rana

SUZHOU, China -- A new cancer drug licensed by Eli Lilly &

Co. was discovered by a six-year-old startup on the outskirts of

Shanghai, and derived from the ovary cells of Chinese hamsters.

Lilly now is planning to test it on Americans.

Rival Merck & Co. aims to test a separate cancer drug in the

U.S. this year, created by another startup near the border with

Hong Kong.

Those aren't outliers. China, long the world's supplier of cheap

pharmaceutical ingredients and copycat pills, is emerging as a

major producer of important new medicines: biotech drugs. China now

boasts the second-largest number of clinical trials involving

biologic treatments -- produced using biological matter such as

animal cells or bacteria -- after the U.S., according to data from

the National Institutes of Health.

The world's biggest drug companies have taken notice.

Merck sent executives to scour scores of Chinese startups, and

set up a dedicated innovation center in Shanghai in 2015. Johnson

& Johnson opened a similar center in Shanghai in 2014 to

identify scientific breakthroughs in China. In the past two years,

Lilly, Merck, Tesaro Inc. and Incyte Co. have signed

multimillion-dollar deals to sell China-discovered biotech drugs

overseas.

The tie-ups are a boost for China's ambition to shake off a

history of scandals, such as a 2008 incident when a blood thinner

called heparin -- made with Chinese ingredients -- killed dozens of

people in the U.S. alone. China is working to overcome a reputation

for poor quality to become an innovator and global producer of

complex products.

Will China transform "overnight? The answer is definitely no,"

said Olivier Charmeil, Sanofi SA's head of emerging markets. But

"when a direction has been set, it's clear that things happen," he

added, noting that China is devoting resources to ramp up

quality.

However, Chinese factories supplying chemical-drug ingredients

around the world continue to fail U.S. regulatory inspections. Last

year, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration barred ingredients from

a Chinese supplier that counts Sanofi, Pfizer Inc. and Novartis AG

as its customers.

Biologic drugs differ from chemical medicines and have

revolutionized treatment of diseases including cancer and diabetes.

They were developed by Western drugmakers in their own laboratories

for decades and are highly profitable -- accounting for eight out

of the world's top 10 best-selling drugs -- according to

consultancy Frost & Sullivan. But the drugs require more than

$1 billion each to develop and can take more than a decade to bring

to market, according to Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers

of America, a trade group.

Under pressure from a string of expensive failures and a

shrinking pool of patent-protected biotech drugs, global drugmakers

are increasingly turning outward to find new breakthroughs.

Enter China. As part of a push to transform the homegrown drug

industry, Beijing has thrown money and incentives at Chinese drug

manufacturers: One program lured back Chinese scientists working

overseas, billions of dollars were poured into technology parks

dedicated to biotech startups, and drug-testing approvals for new

biotech discoveries were speeded up.

Most Chinese startups began by making copies or tweaked versions

of existing biotech drugs, but some are advancing to the riskier

business of creating biologics that haven't been tested on humans

before.

Innovent Biologics Inc., the six-year-old startup near Shanghai,

struck the biggest deal to date for a Chinese drug firm in 2015,

when Lilly paid it $56 million to co-develop three cancer drugs,

including two discovered by Innovent. Innovent stands to earn more

than $1.4 billion over the next decade if the drugs meet

targets.

Inside a small Innovent lab in the industrial town of Suzhou,

dozens of cylindrical glass vessels called bioreactors brim with

cells derived from Chinese hamsters, rodents commonly used in

global medical research. The drug being designed, part of the Lilly

deal, is meant to block a gene hindering the body's ability to

fight cancer.

The process begins by genetically modifying hamster ovary cells

so that they produce an antibody -- or protein -- needed to block

the gene. The cells are then placed inside these bioreactors,

multiplying into billions of new cells over two weeks. The

resulting amber-colored liquid contains large quantities of the

antibody, the main ingredient in Innovent's drug.

One recent afternoon, researchers were running tests to check

the antibody for purity, color and consistency. "You have to get

every step right," said Innovent's founder, Michael Yu, inspecting

results on a screen. Finally, the antibody is packed into hundreds

of tiny vials and ready to be injected into patients.

Innovent has begun testing the drug on patients in China, while

Lilly is preparing an application to begin its own clinical trial

in the U.S. Once the drug is approved, Lilly says it plans to sell

it across the globe, except in China, where it holds joint

marketing rights with Innovent.

Clinical trials -- which involve testing the drug on hundreds of

patients over three phases -- can last over a decade in the U.S.,

and it is only after promising results that companies seek

regulatory approval.

Gaining drug approval in the U.S. makes it easier for companies

to sell products in several other countries without having to

conduct separate tests in each market. China requires its own

tests, though trials here are typically shorter and require fewer

patients than in the U.S., according to ChinaBio, a Shanghai-based

consultancy.

To be sure, not everyone is looking to license Chinese

discoveries. Amgen Inc. and MedImmune Inc., AstraZeneca PLC's

biotech arm, have formed joint ventures with local companies to

bring their own discoveries to China. Pfizer is building a plant to

sell copies of biotech drugs in China.

Nevertheless, China's biotech boom has attracted venture

capitalists, contributing to a record $5.3 billion being invested

in the country's life sciences sector last year, a nearly 10-fold

increase from five years ago, according to ChinaBio.

Lilly set up a venture-capital arm for Asia in 2008 and almost

all of its $500 million in investment since has gone to Chinese

biotech startups.

"China wasn't even on the radar 10 years ago," said Judith Li, a

partner at the fund. "Now it's impossible to ignore."

Write to Preetika Rana at preetika.rana@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

April 10, 2017 05:44 ET (09:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2017 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

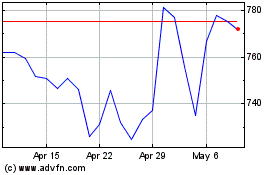

Eli Lilly (NYSE:LLY)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Eli Lilly (NYSE:LLY)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024