By Robert Wall and Doug Cameron

The aviation industry is bulging with orders for new planes. If

only it can get them made.

There were so many almost-finished jetliners, missing their

engines, piled up at an Airbus SE factory in Germany last May that

executives joked they were in the glider business. It ceased to be

funny when a frustrated Qatar Airways canceled orders for four

planes that were months overdue.

"It is making a huge impact on my bottom line. We are, quite

frankly, screaming," said the airline's chief executive, Akbar Al

Baker.

After years of surging orders, including many from fast-growing

Asian and Mideast airlines that sought fuel-efficient jets when oil

prices were higher, the aviation industry is heaving under the

strain. By the end of the decade, Airbus and Boeing Co. must build

30% more planes annually than they do now to meet existing orders,

in one of the industry's steepest production increases since World

War II. The scale of the ramp-up is putting companies to the

test.

Suppliers of seats, toilets and engine parts are stretched to

the limit and sometimes falling short. In one of the worst holdups,

Pratt & Whitney, an engine supplier for a hot-selling new

Airbus model, informed the European plane maker in September it

would ship only 75% as many engines in 2016 as planned.

Both Boeing and Airbus are making adjustments to cope, retooling

factories and tightening oversight of their globe-spanning supply

lines. Boeing said at the beginning of 2016 it would make fewer

planes during the year than in 2015. The move sent Boeing's stock

to its steepest drop in 14 years, though it has since

recovered.

Airbus fell so far behind on its 2016 production schedule it had

to rush out more than 100 planes in December to meet the year's

target. It took the unusual step of increasing staffing at

factories in the final weeks of the year, including the holidays,

and told suppliers to do the same.

Airbus's newest version of its workhorse A320 offers new

engines, but the company had 20 of the planes still waiting for

engines at year-end. By cranking out more older models, filling

back orders, it managed to meet and even exceed its 2016 target of

670 planes.

Today, the yearslong order bonanza pressuring manufacturers

shows signs of tailing off, but that doesn't relieve the urgency to

deliver ordered planes as quickly as possible. Manufacturers

collect most of a plane's price only when they ship it. For Airbus,

cash flow ran steeply negative for much of last year because so

many airliners weren't getting to customers.

Also, for the fiercely competitive Boeing and Airbus, on-time

delivery can keep buyers loyal instead of turning to the arch rival

or to emerging plane producers in China, Russia and Canada. Qatar

Airways, after the Airbus delays, decided to buy some Boeings, a

new 737 model called the Max.

Qatar Airways' Mr. Al Baker blames both of the big two for not

being ready for the order boom, which was fed by low interest rates

in addition to the higher fuel prices of prior years. The

inexpensive financing spurred purchasing by airplane-leasing

companies, which buy about 40% of new planes.

In 2011, Mr. Al Baker ordered 50 Airbus A320 airliners with new,

more fuel-efficient engines, called the A320neo -- an order trimmed

to 46 after his cancellations last year. "Both Airbus and Boeing,

in order to mitigate their risk, will have to start investing in

the industry in order to have a more diversified supply chain," Mr.

Al Baker said.

Airbus, based in Toulouse, France, has moved around shifts and

vacation time for factory workers to align them better across its

manufacturing centers. It may dedicate more resources to

"supporting and understanding proactively possible hiccups with

suppliers in the future," said Tom Enders, the chief executive. He

asked his chief operating officer, Fabrice Brégier, to personally

supervise suppliers.

"We need to educate" them, Mr. Brégier said. "They are on their

way. Some need to continue to make efforts."

At Boeing, meanwhile, Chief Executive Dennis Muilenburg has

staff members and consultants scouring for potential problems that

might delay the first delivery of the 737 Max, expected as early as

May.

In the frenzy to deliver on time, minor snafus can cascade into

big problems. Trouble has arisen with seats, toilets and in-flight

entertainment systems, all in short supply at various times.

Hit by a 2014 strike at a Texas seat maker, France-based

aviation-parts supplier Zodiac Aerospace SA was late delivering

business-class seats, which cost about $100,000 each, for new

Boeing 787s headed to American Airlines Group Inc. in 2015.

Typically, airlines buy seats directly from suppliers but have them

shipped to the airplane manufacturer.

The delay pushed back deliveries of the 787s by four months and

held up fitting new seats in some 777 jets. American switched seat

suppliers. The airline declined comment. Boeing now is backing a

startup seat-maker to prevent shortages.

Zodiac also was late delivering seats and lavatory doors to

Airbus for its A350 long-range jet, at a time when Airbus was

sharply raising production of that plane in 2015. One of the first

buyers, Finnair, received the planes late.

Zodiac's chief executive, Olivier Zarrouati, said his company

relied too heavily on assurances from subsidiaries that make the

parts but has since fixed the problems. Zodiac agreed in January to

be acquired by Safran SA, a French maker of airplane parts, which

has pledged to help Zodiac overcome its problems. The acquisition

still needs shareholder and regulatory approval..

Nothing has been more disruptive than the Pratt & Whitney

engine issue. When Airbus set out several years ago to rejuvenate

its popular 165-seat A320, by giving buyers a choice of two new

engines, orders for the A320neo far outpaced expectations.

For one engine option, Airbus picked CFM International, a joint

venture of General Electric Co. and Safran. For the other, it chose

the Pratt & Whitney unit of United Technologies Corp.

Pratt & Whitney struggled with making the engine fan blades,

which initially took twice as long as managers had expected. The

company said this is improving and extra capacity is coming on

stream to meet its new target.

United Technologies' chief executive, Gregory Hayes, said in

January that it was back on track after struggling with parts

issues. Pratt & Whitney delivered 138 engines in 2016, down

from the planned 200, but expects to build 350 or 400 this year.

The company on Feb. 1 replaced the head of its commercial aircraft

engines business.

CFM also shipped fewer engines than planned last year, 77

instead of about 100. Output is scheduled to jump to more than

2,000 by 2019. CFM this month named a boss to oversee the process

after the contract for the prior head of the joint venture ended.

One CFM plant, outside Lafayette, Ind., is trying to cut in half

the 20 days needed to turn out an engine.

Airbus managed to deliver 68 A320neo airliners last year,

including 39 with the Pratt & Whitney engine. After Qatar

Airways' cancellation of its initial orders, Deutsche Lufthansa AG

became the first airline to take delivery.

This year should be smoother, though delays are likely to

persist, said Airbus's Mr. Brégier. The company expects to triple

its output of the A320neo and build more than 700 airliners in

all.

Boeing, which delivered 748 planes last year, expects this to

rise to 760 to 765 in 2017 as it boosts production of the 737 from

the third quarter, with further increases planned over the next two

years.

--Ted Mann contributed to this article.

Write to Robert Wall at robert.wall@wsj.com and Doug Cameron at

doug.cameron@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

February 23, 2017 16:45 ET (21:45 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2017 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

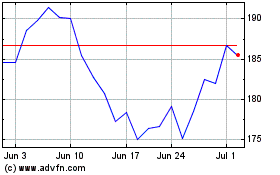

Boeing (NYSE:BA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Boeing (NYSE:BA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024