By Georgi Kantchev

The euro rallied from early losses, following Italian voters'

rejection of a government-backed referendum, but the volatile day

raises concerns about how the currency survives an era of populist

politicians and diverging economies.

The euro was at $1.0765 late Monday in New York, up 0.9% against

the dollar. Overnight, it had been down as much as 1%. The

referendum's failure meant the resignation of Italian Prime

Minister Matteo Renzi. Mr. Renzi's antagonists, the

antiestablishment 5 Star Movement, have questioned the common

currency and called for a nonbinding referendum on Italy's

membership in it.

The referendum sets up a political vacuum in Italy that could be

treacherous for the country's banks. A plan to rescue the weakest,

Monte dei Paschi di Siena SpA, is likely scuttled, and it may need

to be nationalized. If other banks stumble, and if concerns rise

for banks outside of Italy, the euro could be stressed further.

European stock markets rose Monday, except for Italy's, which

was hurt by sharp falls in banking shares and ended down 0.2%.

Monday's calm trading, outside of Italian banks, suggested

investors believe the vote on its own doesn't challenge the

eurozone. There was no clamoring for havens: Long-term German bonds

weakened, as did gold. Italian bonds also fell, and their yields

rose more than Germany's. That gap signals some concern about

Italy, though the gap widened only modestly.

Born in 1999, the euro has survived tougher trials. In 2010, its

member countries set aside deep resistance to paying for each

others' debts and bailed out Greece and then Ireland. The next

year, Portugal. And in following years, Spain, for its banks, and

Cyprus.

The left-wing Syriza party took control of Greece in 2015 full

of rumblings about a return to the drachma. Yet Greece stomached

capital controls and a new bailout and didn't leave the euro.

For investors, however, the repeated tests erode confidence and

reawaken existential questions. "We've seen these games many times

before," said Richard Benson, co-head of portfolio investments at

Millennium Global Investments in London. "The euro recovers, but

each of these political events goes by and the eurozone takes

another hit, so one wonders how long this can be sustained."

And next year will pose many more tests. Elections will come in

2017 in Germany, France and the Netherlands. Consulting firm Bain

& Co. has told clients to "withhold new investments" in Western

Europe, warning that a breakup of the euro is likely.

An eventual fracturing of the common currency would likely be a

calamitous event for financial markets. Widespread capital controls

would be needed to prevent destabilizing rushes of money from

countries deemed likely to have a weak posteuro currency to those

expected to have a strong one. Huge swaths of financial

infrastructure, including derivatives markets and common banking

systems, would need to be disaggregated.

Indeed, fears of the chaos even one country's exit would cause

proved to be a powerful glue holding the eurozone together during

its debt crisis. Since then, there has been a flurry of changes

meant to bind it still tighter, most notably, closer and more

consistent supervision of banks, which triggered trouble in

Ireland, Cyprus and Spain, and tougher fiscal rules, whose

transgressions were the undoing of Greece and Portugal.

Yet the work isn't fully done: The Continentwide "banking union"

is still elusive, and there is little movement toward the

more-distant goal of the sort of federal treasury and budget that

redistribute money across the 50 states of the U.S.

And with a host of euroskeptic parties braying at the heels of

governments now, the prospects for either have receded further.

The euro, as a financial instrument, has declined since early

2014, when it was near $1.40. But that shift has been led by a

sharp divergence in monetary policy: The U.S. Federal Reserve is

moving away from monetary easing, while the European Central Bank

is deep in an experiment of negative interest rates. To a large

degree, a weak euro is a good thing for the eurozone's efforts to

build exports and return ultralow inflation to healthier levels.

Analysts said that monetary-policy split will continue to keep the

euro depressed, but that politics is looming as a force.

"The euro is in a downward spiral," said Francesco Filia, who

manages $300 million as head of Fasanara Capital in London. Mr.

Filia is betting that the euro will fall against the dollar as

France's elections draw closer. "Ultimately, we are very bearish

for the prospects of the European Union surviving the next couple

of years in its current form."

To be sure, the eurozone's demise has been predicted many times

before. The currency enjoys solid popularity among Europeans who

use it. And while euroskeptic parties have made strides in opinion

polls, they have had less success reaching public office in the

eurozone. On Sunday, Austrians voted against a far-right populist

candidate for the largely ceremonial post of president.

"Unless and until an antieuro group is running a euro-area

government, outcomes like today create intraday volatility rather

than trend euro weakness," said John Normand, head of international

foreign-exchange and rates strategy at J.P. Morgan Chase &

Co.

Several analysts said the euro could reach parity with the

dollar next year. That hasn't happened since 2002. Before the

referendum, Deutsche Bank AG forecast the euro would fall to $0.95

by the end of next year, while Citigroup Inc. foresees the euro

tumbling to $0.98 in the next six to 12 months.

"The euro is a politically driven currency now," said Dominic

Bunning, senior foreign-exchange strategist at HSBC Holdings PLC.

Mr. Bunning said he has been recommending clients bet against the

euro since before the referendum, partly because of the rise of

euroskeptic parties.

A mitigating factor for the euro might come from an unexpected

place, a strengthening European economy. There are tentative signs

that the eurozone, which has been plagued by low growth and high

unemployment since the financial crisis, is turning the corner.

The unemployment rate across the 19 countries that use the euro

fell to its lowest level since mid-2009 in October, while retail

sales rose at the fastest rate in more than two years that month,

according to official statistics.Manufacturing and consumer

optimism have also rebounded, data show.

The end of a long period of economic weakness could give the ECB

enough comfort, eventually, to pull out of negative rates and slow

down or stop its bond purchases. That would boost the euro. Another

effect of a strengthening economy may be to dull the

disintegrationist push of populist parties.

The next big test for Europe could come from France, a country

that has helped push eurozone integration. Current polling suggests

that the far-right National Front leader Marine Le Pen is a leading

contender in France's presidential election next year, though she

isn't the favorite. Ms. Le Pen wants to pull France out of the

euro.

Mark Dowding, co-head of investment-grade debt at BlueBay Asset

Management LLP, has sold French bonds in recent weeks ahead of next

year's presidential elections.

"Italy voting out Renzi is one thing, but if the French were to

vote for Le Pen, it could be the beginning of the end for the

euro," he said.

--Christopher Whittall, David Wighton and Ira Iosebashvili

contributed to this article.

Write to Georgi Kantchev at georgi.kantchev@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

December 05, 2016 19:32 ET (00:32 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

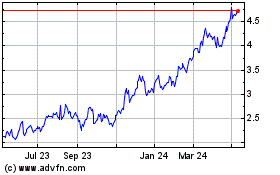

Banca Monte Dei Paschi D... (BIT:BMPS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

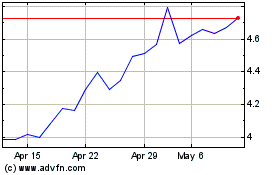

Banca Monte Dei Paschi D... (BIT:BMPS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024