By James R. Hagerty

Hans Becherer stood out from most of the Midwestern lifers at

Deere & Co. Though he grew up in the Detroit suburbs, he was a

graduate of the Harvard Business School, drove imported cars and

knew his way around the capitals of Europe.

After he became chief executive of the farm-equipment maker in

1989, he spurred investments in China, Brazil and other emerging

markets. To help make sales, he made regular trips around the world

to meet leaders, including Nursultan Nazarbayev, the president of

Kazakhstan, who gave him a bear hug. He won more flexible work

rules from unions.

Mr. Becherer (pronounced Becker-er) died Oct. 6 at home in

Denver. He was 81 and had esophageal cancer.

Hans Walter Becherer was born April 19, 1935, and grew up in

Grosse Pointe, a wealthy suburb of Detroit. Both of his parents

were born in Germany, and his father worked as an electrical

engineer. Young Hans pumped gas and worked construction in the

summer. He earned a history degree in 1957 from Trinity College in

Hartford, Conn., where he was president of a fraternity that he

later said was known for wild parties but also held literary

discussions.

After joining the Air Force, he served as a supply officer in

Germany, near Munich. While there, he bought his first sports car:

an Alfa Romeo Spider Veloce.

During a vacation with his sister, Ruth, near St. Tropez,

France, he spotted a young Parisian, Michele Beigbeder, who worked

as a ballerina and model. He introduced himself. They began dating

and married two years later. Her father invited him to a business

lunch, where he met a Deere executive.

Returning to the U.S., he enrolled at Harvard Business School.

During a summer break, he worked as an intern for Deere. After

getting his masters of business administration in 1962, he drove

his Renault Dauphine to Moline, Ill., to take a full-time job at

Deere at $650 a month.

Soon he was posted to Germany as a sales manager. At times, he

had to serve as an intermediary between Germans and Americans. A

plant manager from Moline was astounded to see workers on a German

shop floor taking beer breaks. He ordered tight restrictions on

such breaks, setting off a brief walkout that became known as the

Beer Strike.

"The technical people came out of small-town, middle-American

factories with very little appreciation for communication

sensitivities," Mr. Becherer later told The Wall Street

Journal.

As a promising young executive, he was brought back to Moline in

1967 as an assistant to William Hewitt, the company's cosmopolitan

chairman who also had attended Harvard and adorned the headquarters

with expensive art, including a Henry Moore sculpture. On later

postings, Mr. Becherer scoured Eastern Europe, the Middle East and

Africa to find new customers. He was involved in bartering Deere

combines for jute in India.

After returning to the head office, he won a series of

promotions in the 1970s, when Deere sales boomed, and in the 1980s,

when a farming slump forced the company to cut its payroll by more

than a third. He rose to chief executive in 1989 and chairman the

next year, becoming only the seventh chief of the company founded

in 1837 to make steel plows.

Deere, still rattled by the devastating slump of the 1980s,

remained in cost-cutting mode, but Mr. Becherer and the board

agreed the company couldn't shrink its way to prosperity. So Deere

invested in operations in Brazil, China, India and Russia. Mr.

Becherer also prodded Deere engineers to overhaul the design of

combine harvesters, including by adopting some ideas from

competitors, a deeply unpopular notion.

One of his dreams was to build a state-of-the-art training

center. It would have been his legacy, alongside the elegant

glass-and-steel headquarters built by his early patron, Mr. Hewitt.

The board nixed the idea as too costly.

He served on the boards of Allied-Signal Inc., Schering-Plough

Corp. and Chase Manhattan Corp. He retired from Deere in 2000.

Not long after his retirement, he golfed with Robert Hanson, his

predecessor as CEO, at the Deere Run golf course in Silvis, Ill.,

where the company sponsored golf tournaments. When a golf course

employee didn't recognize him as a Deere grandee, Mr. Becherer was

vexed. Mr. Hanson was less surprised. "He doesn't know yet that

when you're no longer CEO you go from Who's Who to Who's That?" Mr.

Hanson said, according to another colleague who was present.

Adapting to anonymity, Mr. Becherer and his wife spent their

later years in Denver to be near their grandchildren. He enjoyed

fly fishing and walks with his labradoodle, Bruno.

He is survived by his wife, a daughter, a sister and three

grandchildren. A son, Maxime, died in 1998.

Days before his death, after he had already gone into hospice

care and was finding it hard to talk, Mr. Becherer got a phone call

from Pierre Leroy, a former Deere colleague and longtime friend

with whom he had shared Thanksgiving meals and long bike rides.

"Pierre," he managed to rasp, "we really had fun, didn't we."

Write to James R. Hagerty at bob.hagerty@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

October 28, 2016 10:14 ET (14:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

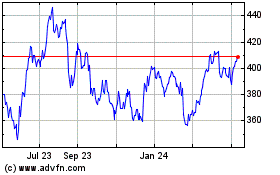

Deere (NYSE:DE)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

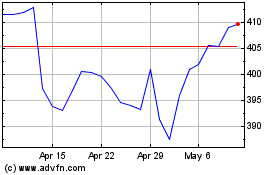

Deere (NYSE:DE)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024