Nearly 10 years ago, executives at Novo Nordisk A/S wondered

whether the company's decadeslong quest to make ever-better insulin

had finally come to an end.

The trigger was an impressive set of results for the company's

newest insulin that suggested the product would be difficult to

improve upon.

"We just sat there and said, 'Wow,' " research chief Mads

Thomsen recalled of the meeting where he and other executives saw

the results. "We had kind of realized we were very close to

perfection."

That realization has forced a gear change at Novo Nordisk, the

world's largest insulin maker. For most of its history, the

publicly held Danish company, which is valued at about 700 billion

Danish kroner ($105 billion), relentlessly re-engineered the same

basic medicine.

Now, it is getting into the complex and more expensive business

of inventing new forms of insulin, bringing it closer to the

riskier drug-discovery activities of the wider pharmaceutical

industry.

In Novo Nordisk's favor is the sheer scale of the diabetes

epidemic, which affects one in 11 adults world-wide and is rising.

At the same time, it is grappling with increasingly intense

competition—its biggest rival in the insulin market is France's

Sanofi SA—and consumers who are less willing or cannot afford to

pay premium prices for incremental improvements.

That tougher environment is reflected in Novo Nordisk's approach

to launching its latest insulin, Tresiba, in the U.S.

Its list price, at $443.85 for 15ml, according to Truven Health

Analytics, is 10% higher than the equivalent volume of its

predecessor Levemir. That is low by historic standards: Levemir

sold at a 43% premium to its predecessor when it launched 10 years

ago, according to Jakob Riis, who runs Novo's North American

operations.

Health plans and employers typically pay a discount to the list

price.

Last week, the company announced it would cut about 1,000 jobs

from its 42,300-strong workforce to reduce costs. The move

underscores Novo Nordisk's struggle to maintain strong growth amid

the competition in the insulin market, which accounts for more than

half its sales.

It wasn't immediately clear what impact the layoffs would have

on the company's new direction.

Novo Nordisk's research costs are low compared with its peers,

according to Dr. Thomsen. He said the company spent about $2

billion on research for each successful drug, compared with $5

billion to $10 billion for most pharmaceutical companies.

Insulin, a hormone produced by the pancreas, converts sugar to a

form that can be stored for future use. People with Type-1 diabetes

can't produce insulin; those with Type-2 diabetes don't produce

enough.

Novo and Nordisk, which merged in 1989, were established shortly

after the early-1920s discovery of insulin to extract and purify

the substance from the pancreases of pigs.

Until recently, most of the company's research sought to produce

a fast-acting insulin that could be injected as a booster at

mealtimes and another "basal" variety that would provide a slow,

steady supply the rest of the time.

Patients spent an average of $736 a year on insulin in 2013, up

from $231 in 2002, according to a recent analysis published in the

Journal of the American Medical Association, though the costs can

add up to thousands of dollars annually for those on

high-deductible health plans.

Novo Nordisk believes it has reached the pinnacle of these

efforts with Tresiba, which remains at a near-stable level in the

blood for 40 hours, longer than the 24 hours offered by the

previous generation.

Now, the company has its sights on new categories of insulin.

Among them: one that selectively acts on the liver; one that can be

taken as a tablet, not injected; and one that acts only when blood

sugar is too high, eliminating the risk of dangerous dips in blood

sugar that occur when there is too much insulin in the blood.

"Some of this is really complicated chemistry," said Thomas Hø

eg-Jensen, a scientific director at Novo Nordisk who helped to

design Tresiba and now leads efforts on glucose-sensitive

insulin.

A team of about four scientists spent three to four years

developing Tresiba, he said. By contrast, about 10 scientists have

been working on glucose-sensitive insulin for four years. He

estimated it would take another two years for the scientists to

produce a version that could advance into human testing.

"The next steps will take innovation to an even higher level,"

Dr. Thomsen said. "But that comes at a very high cost of research

and development."

The amount Novo Nordisk spends on diabetes R&D more than

tripled in the last 10 years, to 10.5 billion Danish kroner ($1.6

billion) last year from 3.2 billion kroner in 2005.

Novo Nordisk's push into more complex research has coincided

with a resolve to stick with diabetes and closely related

conditions such as obesity, rather than diversify into other

disease areas.

The company's near-exclusive focus on diabetes has helped to

make it a top performer in terms of return on research dollars.

Novo Nordisk's return on research investment, at 15%, is one of

the highest in the industry, according to analysis by SSR LLC. By

comparison, Novartis AG and GlaxoSmithKline PLC's returns were 7%

and 3% respectively.

Now that the company is venturing into more difficult territory,

that narrow focus will be put to the test.

"The convenient explanation for [Novo's high productivity] is

that they just stuck to their knitting," said Richard Evans, an

analyst at SSR. But another is that the "degree of risk-taking in

R&D was limited."

Dr. Thomsen said Novo Nordisk's research productivity is likely

to decline as the company invests in projects that are more prone

to fail. But he said Novo Nordisk can afford to take those risks

because of the revenue-generating potential of its portfolio,

including a treatment called Victoza that increases insulin

secretion by the pancreas in Type-2 diabetes patients.

Novo Nordisk also faces competition from companies not

historically linked with insulin. Merck & Co. is leading the

race to develop glucose-sensitive insulin, having just completed a

safety study in humans.

"We are a stubborn company that does make decisions that seem

risky to some," Dr. Thomsen said. "But with the competence of the

company, it seems logical to us."

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

October 02, 2016 23:25 ET (03:25 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

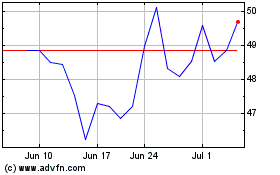

Sanofi (NASDAQ:SNY)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

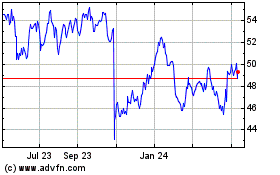

Sanofi (NASDAQ:SNY)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024