By Christopher Whittall

LONDON -- Investors are now paying for the privilege of lending

their money to companies, a fresh sign of how aggressive

central-bank policy is upending conventional patterns in

finance.

German consumer-products company Henkel AG and French drugmaker

Sanofi SA each sold no-interest bonds at a premium to their face

value Tuesday. That means investors are paying more for the bonds

than they will get back when the bonds mature in the next few

years.

A number of governments already have been able to issue bonds at

negative yields this year. But it is a rare feat for companies,

which also ask investors to bear credit risk.

The move has been driven by the European Central Bank's

expansion this summer of its bond-buying program from government to

corporate debt, creating more demand for bonds and pushing down

their yields. But even if the pricing is explainable, some

investors are still trying to come to terms with the idea.

"We're trying to get our heads around it," Edward Farley, head

of European corporate bonds at PGIM Fixed Income, said of Tuesday's

deals. "It seems pretty bizarre to ask a corporate to look after

your money and give you back less in two to three years' time."

It may seem counterintuitive to buy bonds at a price that

guarantees a loss going in. But investors have limited options

given even deeper negative yields on much government debt and the

costs of holding cash. Some may be betting that central-bank buying

will drive prices even higher, letting them sell the bonds for a

profit before they mature. Others may be required to invest in

certain types of bonds.

Henkel, maker of Persil detergent and Loctite caulks, sold a

EUR500 million ($558 million) bond that matures in two years, while

Sanofi, an international pharmaceuticals company, sold a EUR1

billion bond that comes due in January 2020, according to deal

notices released to investors. Both deals will put buyers only

narrowly in the red -- they each priced with a yield of minus-0.05%

-- and both were part of larger packages that included bonds with

low but positive yields, the notices said.

"With interest rates reaching record lows, we decided to be

opportunistic," a spokeswoman at Sanofi said.

Henkel declined to comment.

Yields on corporate debt have plunged in recent months as

investors have pushed up prices in the scramble for returns.

Roughly EUR706 billion of eurozone investment-grade corporate bonds

traded at negative yields as of Sept. 5, or over 30% of the entire

market, according to trading platform Tradeweb, up from roughly 5%

of the market in early January.

Tuesday's deals, however, are among just a handful of corporate

offerings that have actually been sold at negative yields. They

include offerings of euro-denominated bonds earlier this year by

units of British oil giant BP PLC and German auto maker BMW AG,

according to Dealogic. Germany's state rail operator, Deutsche Bahn

AG, also has issued euro-denominated bonds at negative yields.

The ECB launched its corporate bond-buying program in early June

and had bought over EUR20 billion of corporate bonds as of Sep. 2.

Most of its purchases came in secondary markets, where investors

buy and sell already issued bonds. The central bank meets Thursday

and will decide if it should expand its current bond-buying

program.

The purchases have helped set off a burst of issuance following

the traditional summer lull in local capital markets. Last month

was the busiest August on record for new issuance of

euro-denominated, investment grade corporate debt, according to

Dealogic.

Also on Tuesday, commodities group Glencore PLC sold about EUR1

billion in bonds in one of its first forays into capital markets

since its shares and bonds were sold off last fall amid concerns

over debt levels and falling commodity prices. Glencore said it

would use the proceeds to pay down debt.

Central banks around the world have adopted increasingly

aggressive efforts to boost weak economic growth. A number have

pushed their benchmark interest rates into negative territory.

Others have bought government bonds to pull down interest rates.

The ECB is buying corporate bonds as well, while the Bank of

England is expected to start its own purchases of such securities

in mid-September.

It isn't clear that the approach is working; ECB President Mario

Draghi said in July that the bank had seen a continued increase in

demand for loans from companies and households during the second

quarter, as ECB policy significantly improved borrowing conditions.

Yet while companies are raising more money, analysts believe they

are sitting on much of it or using it to refinance more expensive

debt.

The ECB's latest survey of bank lending in the euro area,

published on July 19, found that companies were borrowing more to

take advantage of low interest rates, to pay down debt and build up

inventories or working capital, and to carry out deals. But the

number of companies borrowing to make fixed investments slid

further in the second quarter, the survey found.

Nonfinancial corporations in Europe, the Middle East and Africa

had EUR921 billion in cash balances as of December, according to a

report from Moody's Investors Service on the companies it rates, up

about 5% from a year earlier.

Many companies are holding back from spending for the very

reason that central banks are launching their stimulus: poor

economic prospects.

"Companies need a compelling argument to expand their

businesses, either through investment or acquisition, based on an

upbeat economic outlook and limited risks in the near term," said

Zoso Davies, a credit strategist at Barclays PLC.

Some economists believe measures like negative interest rates

may spur greater caution on the part of businesses and consumers by

expressing central-bank fear over the economic outlook.

Meanwhile, investors are faced with portfolios of

negative-yielding bonds and pension funds with yawning deficits to

fill. Around $13 trillion worth of bonds traded with a negative

yield in late August, according to J.P. Morgan Asset Management. At

the beginning of 2014, the figure was close to zero.

The lurch lower in borrowing costs is benefiting U.S. companies.

They have accounted for just over one-fifth of the investment-grade

new issuance in euro-denominated debt this year, according to

Dealogic, more than any other single country.

Some investors also are shifting from European debt into U.S.

corporate bonds, which offer higher returns. That further pushes

down borrowing costs for American companies.

"Most well-rated companies now have funding opportunities at

zero or negative yields," said Mark Lynagh, head of EMEA

investment-grade corporate bonds at BNP Paribas SA. "That's the

environment we're in."

Tom Fairless, Scott Patterson, Noemie Bisserbe, Ellen Emmerentze

Jervell and William Wilkes contributed to this article.

Write to Christopher Whittall at

christopher.whittall@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

September 07, 2016 02:47 ET (06:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

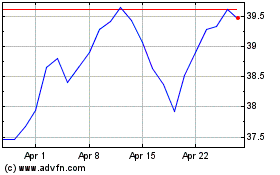

BP (NYSE:BP)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

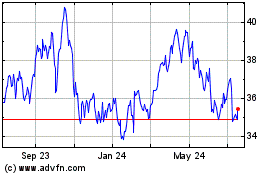

BP (NYSE:BP)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024