By Jack Nicas

Yahoo Inc.'s proposed sale to Verizon Communications Inc. puts

an exclamation point on a tumultuous two-decade run that began with

success as the web's organizer and ended with a string of failed

leaders and strategic blunders.

The internet company's prolonged decline could serve as a

classic case study in defining a business whose many chief

executives struggled to answer: What is Yahoo?

Begun in a Stanford University dorm room in 1994, it spent its

first decade building scale as the internet's portal. Then, as

Google Inc. and Facebook Inc. -- two companies it nearly acquired

-- built lucrative footholds in search and social media, Yahoo fell

behind the fast-moving internet economy it helped create. Visitors

and revenue dwindled as it strained to innovate across its myriad

services.

"If you're everything, you're kind of nothing," said Brad

Garlinghouse, a former Yahoo executive who in 2006 wrote the "

Peanut Butter Manifesto, " an internal memo criticizing the company

for spreading itself too thin. "The sad reality...is it never

solved its core identity crisis."

Mr. Garlinghouse said Yahoo's fluctuating strategies often

confused employees. He recalled asking managers at a retreat in

2006 the first word they thought of when he named a company.

Google, eBay and others yielded clear answers -- "search" or

"auction." Yahoo didn't. Managers said "mail," "news," "search,"

and other things.

A parade of CEOs over two decades amplified the confusion,

seesawing its emphasis between tech and media.

Co-founders Jerry Yang and David Filo initially built their

index, called "Jerry and David's Guide to the World Wide Web,"

while procrastinating on a thesis project.

Their first CEO, a silver-haired former rocker named Timothy

Koogle, said he joined a company in 1995 with no revenue and six

employees that a recruiter told him "were in desperate need of

adult supervision."

Two years later, Yahoo was among the most-visited websites. It

sorted 735,000 sites and offered free email, news and chat rooms,

attracting 25 million unique users monthly.

Skyrocketing internet usage fueled growth to 100 million users,

2,000 employees and a roughly $125 billion market value by 2000.

Unlike early peers, Yahoo also was profitable, partly because it

pioneered online advertising.

Then the dot-com bubble burst. From a peak price on Jan. 3,

2000, Yahoo's stock plunged 93% over 20 months. Mr. Koogle resigned

in 2001, and the company embarked on its first turnaround

effort.

The next chief, former Warner Bros. executive Terry Semel ,

pushed Yahoo further toward becoming a media company. He aimed to

collect more fees for premium services, including an astrology

hotline charging $14.95 a question. Yahoo stopped investing in

search as the internet's sprawl became too much for a human-curated

index.

Meanwhile, another pair of Stanford graduate students had built

a computer-powered search engine they called Google. It would

become Yahoo's undoing.

Yahoo hired Google in 2000 to power its searches, branding its

search box with Google's logo. Mr. Semel discussed buying Google

with founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin for $1 billion, but they

couldn't agree on price.

By 2002, Google's greater sway over internet commerce sent its

revenue soaring.

Mr. Semel shifted strategies. Yahoo paid $1.9 billion for two

search-technology firms and began powering its own searches in

2004. Mr. Semel also missed another acquisition, which would have

given Yahoo a flagship social-networking property and a coveted

young audience. In 2006, Yahoo discussed paying $1 billion for

Facebook, but talks again ended over price. Facebook's market value

today is more than $340 billion.

But Yahoo never caught up. By 2007, when Mr. Semel resigned,

Google's sales were more than double Yahoo's $7 billion.

Mr. Semel and other Yahoo ex-CEOs declined or didn't respond to

requests for comment.

Yahoo next turned to Mr. Yang as CEO. The co-founder vowed an

overhaul, saying "there will be no sacred cows."

In early 2008, Microsoft Corp. made an unsolicited offer to buy

Yahoo for about $45 billion, a roughly 60% premium. Mr. Yang and

his board rejected Microsoft's advances for months. Angry

investors, including Carl Icahn, tried to oust Mr. Yang and

eventually won three board seats.

Asked at a Wall Street Journal conference that year to define

Yahoo, Mr. Yang struggled with a simple answer. "I think of Yahoo

as, we have to be incredibly relevant and meaningful to consumers,"

he said. "And we've defined that around a starting point. We want

you to start your day at Yahoo."

That November, Mr. Yang resigned.

His successor, former Autodesk Inc. chief Carol Bartz, swung

Yahoo back toward media. She invested in news, sports and finance,

hiring journalists and buying a company that produced cheap,

clickable content.

The moves disappointed. A series of executives left and revenue

began a long decline. Ms. Bartz was fired by phone in September

2011. Rumors of a sale soon swirled again.

The next hire, PayPal President Scott Thompson, emphasized

e-commerce. But before he could carry out his turnaround plans, he

resigned in 2012 over discrepancies in his academic record.

Yahoo returned to its tech roots in 2012 by hiring Marissa Mayer

, a fast-rising product manager at Google, generally delighting

investors and employees hopeful for a fresh start.

Ms. Mayer focused on improving products like mail and the

photo-sharing website Flickr, while boosting investment in mobile

software, online video and search. To replenish Yahoo's talent, she

also spent over $2 billion acquiring more than 50 startups.

But even she struggled to define Yahoo, Ms. Mayer argued that

Yahoo should be central to people's "daily habits," whether

searching the internet or checking email. The strategy failed to

halt the talent departures and revenue declines. If anything, it

laid bare a truth about Yahoo: It remains an ambiguous internet

portal.

Some former employees said the root of Yahoo's slow decline was

simpler: It missed the phenomena of search, social media and

mobile.

"What Yahoo is going through today is not because of decisions

they made three years ago," said venture capitalist Andrew Braccia,

Yahoo's former search chief. "It's because of decisions they made

10 years ago."

Write to Jack Nicas at jack.nicas@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

July 26, 2016 02:49 ET (06:49 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

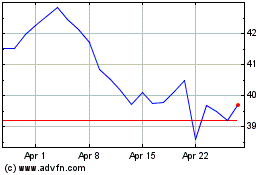

Verizon Communications (NYSE:VZ)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

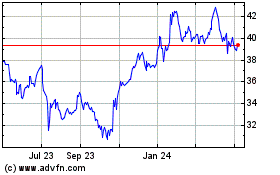

Verizon Communications (NYSE:VZ)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024